Socrates, Plato and Aristotle: First Philosophy

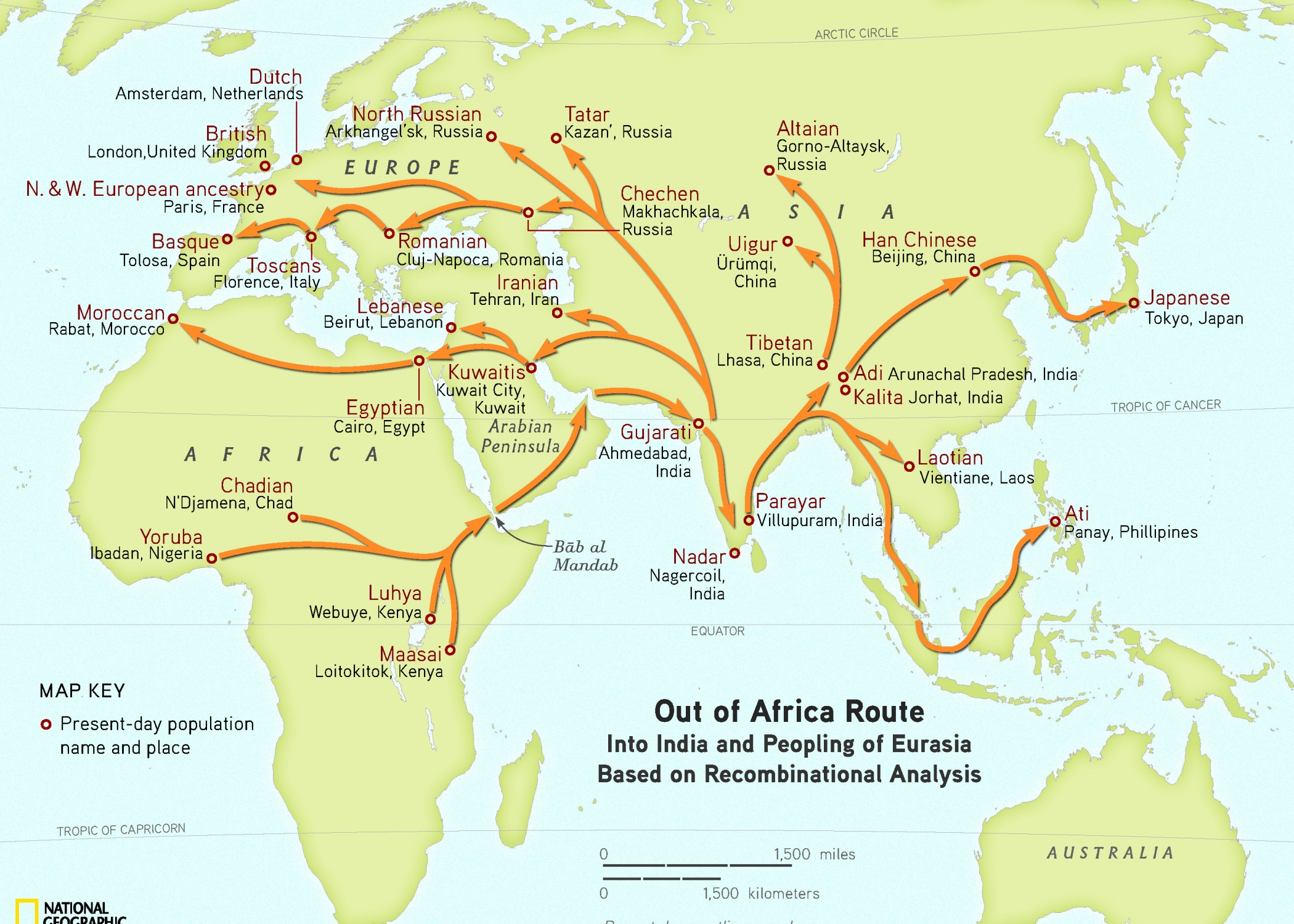

Leaving aside the Indo-Aryan Vedic tradition, representing the root philosophical and religious tradition of the East, the emergence of philosophy as a branch of thought ran parallel with the advent of Ancient Greek civilization. What was unique about this development, unique in fact even from the Vedic tradition, was that it emerged as a branch of thought complete divorced from any religion tradition, or mythology and theos, as the Greek philosophers and mythologians more commonly referred to it[1].

In Ancient civilizations such as the Sumer-Babylonian culture, Ancient Egypt, Ancient Greece, and even Ancient Judaism, there existed a very strong correlation between religion and authority. The priesthood classes in these civilizations had a vested interest in keeping the well-established order of society, and ensuring that access to divinity was kept out of the hands of the general population. In other words, religious authority and political power were very closely tied in these ancient civilizations, and in almost all cases political authority was connected to a divine right, leaving open persecution to those that did not ascribe to this belief system or those that rebelled from it in any way. The religious traditions of these cultures then, both the cosmological as well as mythological aspects, were designed to establish this authority and reinforce it, and even formed the basis of the political power[2].

The Ancient Greeks however stepped away from this very ancient pre-historical connection between the ruling class and its connection to divine authority, and arguably this development represented their greatest contribution to Western civilization. This divorce of religion from philosophy, or more aptly referred to as the development of metaphysics, i.e. the pursuit of knowledge and truth for its own sake, and in turn the establishment of the concept of the logical separation from church and state which naturally grew out of this development, gave rise to not only philosophy and metaphysics, but also math, geometry, logic and even democracy which form the basis of modern Western civilization to this day.

Like any great discovery or evolutionary change however, this development did not happen naturally and without resistance from those who considered the developments as a threat to their authority. And from Charlie’s perspective, this revolution – for it was in fact a revolution in the true sense of the word – was embodied in the life and times of Socrates, who died for his beliefs at the hands of the Greek council and authority in much the same way that Jesus was put to death by the Jewish priestly authorities some five centuries later.

The word “philosophy” comes from the Greek philosophia, which translated into English means literally “lover of wisdom”. The term itself is supposedly to have originated with Pythagoras[3], the ancient Greek mathematician and philosopher who is based known for his Pythagorean Theorem which established the relationship between the three sides of a right angled triangle, namely, , but who also was a philosopher and metaphysician in his own right. In Ancient Greece, philosopher was used to describe those teachers of wisdom and knowledge that disseminated such learning with no financial exchange involved, the dissemination of wisdom and truth for their own sake if you will, as juxtaposed to the sophists[4] who at the time were noted for the exchange of such learning for money and carried with them a negative context from the society at large.

Pythagoras, beyond his mathematical genius, was a philosopher and mystic as well who lived circa 570 BC to 495 BC, overlapping with the life of Socrates for some thirty years or so. He not only contributed to mathematics and philosophy, but also founded a religious movement called Pythagoreanism which among other things had a fairly well developed cosmology that departed from the traditional mythological and cosmological traditions which rested on the belief of the gods as the creators and benefactors (or malefactors in some cases) of mankind. It is believed that Pythagoreanism also held that the soul was a a more permanent construct than the body and existed beyond natural death, i.e. belief the transmigration of the soul which diverged from the concept of the Ancient Greek notion of hell as reflected in their mythological tradition of Hades or the underworld which was prevalent in much of Ancient Greek mythology.

Although the specifics of Pythagorean philosophy and metaphysics is debated by modern scholars given the scarcity of his extant work (much of what we know of Pythagoras and Pythagoreanism comes to us via indirect sources such as Aristotle and Plato among other ancient authors), it is safe to assume that his metaphysics and cosmological world view had a strong mathematical basis, setting the stage for further development of the role of mathematics, and in turn reason, in the philosophy and metaphysics of Plato and Aristotle, reinforcing the notion that mathematics played a crucial role in mankind’s understanding of the universe (kosmos in Greek), principles that permeate not only modern day Western metaphysical beliefs, but also of course modern day physics in both its theoretical and classical forms[5].

One of the best indications of the influence of Socrates on the development of philosophy, his ideas being primarily represented by the writings of his best known pupil Plato, is the more modern delineation of philosophical systems into pre-Socratic philosophy to the philosophical and metaphysical systems of belief that came after Plato, marked most notably by Aristotleanism and Neo-Platonism among other philosophical systems. In other words, in terms of the evolution of what the ancients termed philosophy, which provides the basis for all of the branches of knowledge that today we would categorize as science, biology, ethics, metaphysics, socio-political theory, and even psychology, current historians and scholars basically divide philosophical history into pre-Socratic, Platonic, and Aristotelian, and then post-Medieval philosophy as represented by the works of Aquinas, Descartes, Kant, and Newton among others.

The gap in centuries between the Ancient Greek contributions to philosophy down through the centuries following the introduction of Christianity into the Western world illustrates just how broad and far reaching an influence the Ancient Greek philosophers had on the development of the Western mind and even on Western civilization as a whole given the broad scope of the topics covered in their works. The advent of Christianity in the centuries following the death of Jesus however, traditions which had their own underlying mythological and cosmological beliefs (much of which were borrowed from the Jewish traditions from which Christianity was born, i.e. the Old Testament), predominantly replaced, or at least were superimposed upon, the philosophical and metaphysical systems that were developed by the Ancient Greeks. It was not until many centuries, and even millennia later, not until the power of the Church and the associated threat of persecution for non-believers in the Western word began to wane, that the work of Plato and Aristotle could begin to be expanded upon and drawn from in a purely metaphysical, and even scientific, context.

Having said that, despite the influence of Christianity in the millennia or so after the death of Christ, the work of Plato and Aristotle was not completely abandoned by Christian theologians and philosophers. Of course Christian religion had a profound influence on the theology and metaphysics (if you could call it that) of the Western world in the centuries following the death and crucifixion of Jesus, the metaphysics and cosmology as laid out by Aristotle and Plato did have some influence later Christian scholars and theologians, if for no other reason as providing the metaphysical and logical framework from within which the Holy Trinity and the divinity of Jesus could be established.

This influence can be seen in the development of Neo-Platonism which took shape in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD and incorporated Egyptian and Judaic theology into the metaphysics of Plato and was also espoused most notably by St Augustine (354-430AD) who incorporated Judeo-Christian theology with Platonic thought. Gnosticism, which also flourished in the few centuries following the death of Jesus and in many respects can be seen in contrast to some of the more dogmatic Christian beliefs of the time, borrows some of its theology and metaphysics from early Christianity but also from some of the more esoteric components of the Zoroastrianism and some of the Greco-Roman mystery religions of the day. Scholasticism, a mush later development which is reflected most notably in the works of Thomas Aquinas from the 13th century AD, dominated the monastic teachings of the Christian Church for the few centuries after the turn of the first millennium AD and not so much reflected a particular world view, or philosophy, but more so a mode of learning adopted from its Greek predecessors, focusing on the use of reason and dialogue, i.e. dialectic and inference, as the means to arriving at truth.

From Charlie’s perspective then, the Dark Ages, as marked by the fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century AD until the advent of the Renaissance in the late 14th century some one thousand years later, could be categorized to a certain extent as a step backwards with respect to the establishment of the supremacy of reason and metaphysics over theological and mythological beliefs, reflecting the reinforcement of the use of religion and theology to establish and protect the power of the elite and ruling class which in this case was The Church and the ruling class whose authority rested on the Church. In brief, from Charlie’s perspective, it was the re-establishment of religion as reflected in the dogmatic belief systems of the Church as the basis for authority (and even law), which stifled pure metaphysical and philosophical pursuits throughout the Dark Ages, ironically enough having exactly the very opposite effect that Jesus intended when he rebelled against the Jewish religious authorities of his day, namely the establishment of the divine as every individual’s right: “Neither shall they say, Lo here! or, lo there! for, behold, the kingdom of God is within you.” (Luke 17:21)

Although none of the complete works of pre-Socratic philosophers survive today in full, we do have excerpts and references to their work that allude to who these philosophers were and to some extent their metaphysics, theology, and philosophy.[6] Furthermore, it is clear from the works of Plato and Aristotle that at least to some degree they were influenced by them, even if only within the context of disagree with their fundamental tenets or conclusions. Socrates himself, even if he did not espouse to any of the specific doctrines that were laid out by contemporary or pre-historical philosophers, at the very least laid the groundwork from which subsequent philosophers could freely teach and proselytize their respective doctrines.

All of these pre-Socratic philosophers, and Socrates himself if we are to believe the portrayal of him by Plato, shared the common principle of the rejection of the hitherto traditional mythological and cosmological explanation of reality that permeated ancient thought, and to a great extent all of them attempted to answer such fundamental questions of the origin of the universe and the nature of reality in a more rational, reasonable fashion as contrasted by the traditions that came before them and were predominant in their time[7].

Although Socrates didn’t author any works himself, at least none that are extant and survive down to us today, his teachings and life do survive in the indirect accounts of his final days by his most prolific disciples, namely Plato and Xenophon, as well as in indirect accounts and references in the works of other semi contemporary Greek authors such as the Greek satirical playwright Aristophanes[8], along with of course references in the works of Aristotle, the most prominent student of Plato and an alumnus of the Academy which Plato founded.

Socrates life’s end is marked by his execution by Greek authorities for, at least according to Plato, corrupting the minds of youth and challenging the legitimacy of the gods as well as the established authority of the aristocracy of Greek society of the day. Both Plato and Xenophon wrote works describing the last days of Socrates and the trial specifically, where Socrates attempts to defend his position as simply a seeker of wisdom and man of virtue, almost enticing his accusers to sentence him to death rather than banish him to some foreign land.

Plato was by far the most prominent of Socrates’s disciples and was a prolific author, all of his writings however coming after the death of his mentor and therefore at best represent at least one generation removed of the actual life and times of the great martyr who as the story goes sacrificed his life in the name of truth and knowledge[9]. Plato however is named specifically in the Apology by Socrates himself as being present at the day of the trial however, so there is some evidence, albeit disputed by some scholars, that at least some of Plato’s accounts of Socrates in his dialogues represent first-hand accounts by direct witnesses of events. But taken as a whole though, the life and times of Socrates, from whose example stemmed the great lives and works of both Plato and Aristotle must be looked at through the rose colored lens of his successors who clearly held him in great esteem.

Socrates then personifies what we conceive of today as the prototypical philosopher, despite the contributions of the men that came before him. However what the ancients considered philosophy and what we consider philosophy today, and in turn the field of metaphysics, are conceptually similar but at the same time very different things, the ancient term being much more broadly used to cover a wide variety of topics and branches of thought. The ancient philosophical doctrines of Socrates (as reflected in Plato’s earlier work), the works of Plato himself as reflected in his later works that most scholars agree represent Plato’s own philosophical and metaphysical beliefs, and the works of Aristotle not only explored concepts which we today would consider fall under the category of philosophy, but also covered topics such as theology, ethics, the underlying principles of logic and reason, as well as what we today would call metaphysics, or the study of the nature of reality and knowledge itself. All of these topics fell under what the ancients termed “philosophy”, or more specifically what Aristotle referred to as epistêmai (which is typically translated as “sciences” but is the plural of the Greek word for knowledge).

It must be kept in mind, when looking at and reviewing the authors of Plato and Xenophon in particular who both wrote what are considered to be direct accounts of the last days of Socrates, that the political backdrop was a time of war, a war that affected the entire Greek realm at the time. The Peloponnesian War was the great conflict between Athens and her empire and the Peloponnesian League led by Sparta at the end of the 5th century BC (431 to 401 BC), the termination of which marked the end of the golden age of Athens, after the loss of which was relegated to a secondary city-state in the Ancient World.

This conflict raised many questions as to the nature of political systems in general to the great thinkers of the day, as Sparta’s form of government differed in many respects to that of Athens, and given the war that had such a significant impact on all of Ancient Greece and its bordering city-states at the time, much of the philosophical works of Plato, as well as Aristotle in fact, analyzed the competing socio-political systems of the day and proffered up opinions, philosophical and otherwise, upon which system of government was the best. From Charlie’s perspective, it was from this socio-political self-analysis and introspection, stemming from the great perils and destructive force of war, that democracy in its current form was forged.

Therefore the role of the state, the exploration into the ideal form of government, and the role of the philosopher within the state, topics that would not be classically consider as philosophical inquiries today, is the main topic that runs through Plato’s Republic, arguably one of his most lasting and prolific works. In this text, Plato explores the various forms of government prevalent in ancient Greek society and specifically delves not into the meaning of justice and virtue. He also, through the narrative of Socrates, explores the role of the philosopher in society, even going so far as to speak of the utopian form of government being one that is led by the “philosopher-king”.[10]

In a broader sense, The Republic portrays Socrates, along with other various members of the Athenian and foreign elite, discussing the meaning of justice and various forms of government, and examines whether or not the just man is happier than the unjust man by comparing and contrasting existing regimes and political systems, as well as discussing the role of the philosopher in society. All of these themes must have crystallized in Plato’s mind and life after the death of his beloved teacher Socrates given the socio-political context within which he was put to death. Plato’s concern with the ideal city-state, reflected in the title of the work that was given to it by later historians and compilers of his work on this topic, i.e. The Republic, focused on the value and strengths and weaknesses of democracy as it existed in Ancient Greece, again an important topic of the day given the broad impact of the Peloponnesian War on the world of Ancient Greece at the time and the competing forms of government each side of the conflict espoused.

Another example of the importance of the state in the early philosophical works of the ancient Greeks comes from Aristotle’s Politics. Here Aristotle continues Plato’s exploration into various forms of government and their pros and cons, looking specifically at the government of Sparta in one passage, describing it as some combination of monarchy, oligarchy and public assembly/senate of sorts, all of which were combined to balance power, in many respects similar to the balance of power as reflected in the House, the Senate and the office of the President in the United States today.

Some, indeed, say that the best constitution is a combination of all existing forms, and they praise the Lacedaemonian [Spartan] because it is made up of oligarchy, monarchy, and democracy, the king forming the monarchy, and the council of elders the oligarchy while the democratic element is represented by the Ephors; for the Ephors are selected from the people. Others, however, declare the Ephoralty to be a tyranny, and find the element of democracy in the common meals and in the habits of daily life. At Lacedaemon, for instance, the Ephors determine suits about contracts, which they distribute among themselves, while the elders are judges of homicide, and other causes are decided by other magistrates.[11]

So government then, its role and purpose, as well as the role of the individual citizen, were clearly very important topics of the early Greek philosophers and you’d be hard pressed to believe that to at least some extent they influenced the development of various political systems in their day. But their most lasting contribution arguably was their devotion to the pursuit of knowledge and truth for their own sake, as opposed to the pursuit of knowledge to establish the legitimacy of authority and the ruling class which had been the pattern that had existed for centuries if not millennia before them, as well as their creation of institutions of learning from which this new field of study could be practiced and taught, passing its tenets down to later generations not only orally but through a written tradition for further enquiry and analysis by subsequent students, as reflected in the works of Plato and Aristotle which survive to this day.

Plato, and in turn Aristotle, then should be considered the first metaphysicians in the modern day sense of the word, a metaphysician in this sense being defined as someone who attempts to create and describe a framework within which reality can be described, as well as the boundaries which knowledge and truth can be ascertained, the prevailing characteristic of such a quest being the implementation of reason and logic as opposed to myth or any theological framework which rested on faith. They called this search and exploration philosophy, but the meaning of the term in Greek implied not only at the study of the true nature of knowledge and reality, but also the source of virtue and ethics and their relationship to society at large. In the much quoted words of Alfred North Whitehead, a prolific and influential philosopher and mathematician of the early twentieth century:

The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato. I do not mean the systematic scheme of thought which scholars have doubtfully extracted from his writings. I allude to the wealth of general ideas scattered through them.[12]

Plato’s works are classically divided into three categories – his early dialogues, more commonly referred to as the Socratic dialogues, which focused on the last days of Socrates along with what are presumed to be a summary of Socrates’ philosophy, the Middle dialogues where most scholars agree Plato starts to explore his own philosophical systems of belief, and his Late dialogues where Plato explores his metaphysics, philosophy, theology and cosmological views in greater detail. It is from Plato’s early dialogues that much of what we know about the life and times of Socrates survives to us today.

Plato wrote in dialectic[13] form, exploring theoretical and metaphysical concepts by the use of a narrative or dialogue between various characters, some of whom were verifiably historical and others whose place in history is unknown, exploring esoteric and metaphysical topics from varying points of view in order to arrive at some sense of truth or essence of the topic at hand. Plato believed, and this view was inherited to a certain degree by Aristotle, that the most direct and powerful way to arrive at truth or the essence of an abstract topic was through dialogue, and so almost of all of his writings were drafted in this form. From Plato’s perspective, it was only through dialectic, through the bantering and discussion of varying points of view by several individuals, that the truth or wisdom of a certain topic could be revealed. This form of writing and exposition by Plato can be viewed as evidence of Plato’s insistence that pure, absolute truth is unknowable, but can be explored or better understood by evaluating all sides of an issue or topic and using reason and logic to arrive at understanding, even if absolute truth is elusive.

Socrates plays a significant role in many of Plato’s dialogues, and although it’s not clear to what extent the narratives that Plato speaks of are historically accurate, Plato does make use of a variety of names, places and events in his dialogues attributed specifically to Socrates and others that lend his dialogues a sense of authenticity, be they historically accurate or not[14].

Taken as a whole however, given the philosophical and metaphysical nature of the topics Plato explores in his extant work, historical accuracy isn’t necessarily an imperative for him. In other words, Plato is not attempting to provide any sort of historical narrative but attempting to lay out alternative points of view on a variety of topics to yield knowledge and truth regarding esoteric topics that had hitherto been unexplored. In other words, given the purpose of Plato’s dialogues and extant work, the veracity of the individual beliefs of the persona in his dialogues, or even the accuracy of events which he describes, are of less importance and relevance than the topics which he discusses as well as the means by which he explores the topics – namely dialectic or dialogue. So although it is safe to assume that the life and teachings of Socrates formed much of the basis of many of the philosophical constructs that Plato covers in his extant work, particularly in his early, or Socratic dialogues, just as in the analysis of any ancient literature or culture, the historical and political context within which the works were authored must be considered when trying to determine their import and message.

The essence of Plato’s metaphysical world view is probably best encapsulated in his theory of forms, as elucidated in the allegory of the cave buried deep in The Republic, a metaphor supported by his analogy of the divided line, the sum total of which lays out his view of the nature of reality in its progressive forms as shadow, form, the light upon which the world of name and form reveals itself, and then the source of all knowledge, i.e. the Sun. His analogy of the divided line is the beginning of his explanation into this world of Forms and their relationship to the what he considers to the be illusory, or less real, world of the senses:

Now take a line which has been cut into two unequal parts, and divide each of them again in the same proportion, and suppose the two main divisions to answer, one to the visible and the other to the intelligible, and then compare the subdivisions in respect of their clearness and want of clearness, and you will find that the first section in the sphere of the visible consists of images. And by images I mean, in the first place, shadows, and in the second place, reflections in water and in solid, smooth and polished bodies and the like…

Imagine, now, the other section, of which this is only the resemblance, to include the animals which we see, and everything that grows or is made.…

There are two subdivisions, in the lower of which the soul uses the figures given by the former division as images; the enquiry can only be hypothetical, and instead of going upwards to a principle descends to the other end; in the higher of the two, the soul passes out of hypotheses, and goes up to a principle which is above hypotheses, making no use of images as in the former case, but proceeding only in and through the ideas themselves (510b)…

And when I speak of the other division of the intelligible, you will understand me to speak of that other sort of knowledge which reason herself attains by the power of dialectic, using the hypotheses not as first principles, but only as hypotheses — that is to say, as steps and points of departure into a world which is above hypotheses, in order that she may soar beyond them to the first principle of the whole (511b).[15]

In this section of The Republic, which precedes his more graphic metaphor of his Theory of Forms as told in his Allegory of the Cave, albeit wrapped up in the middle of a socio-political work, does represent from a Western standpoint the one of the first prolific and well-articulated forays into the world of metaphysics, i.e. the exploration of the true nature of reality that underlies the world of the senses, and attempts to explain our place in this world and the illusory and shadowy nature of the objects of our perception independent of any religious or theological dogma. It also illustrates the prevalence of geometry and mathematics as a one of the primary means to which this reality can be understood, paving the way for further mathematical conceptions of reality brought forth by Aristotle among others.

In in the Allegory of the Cave[16], Socrates describes a group of people who have been chained to a wall in a cave for their whole lives, a chain which does not allow their heads to move and therefore they can only see what is directly in front of their field of vision. There is a fire behind them, which casts shadows upon images and forms that are moved behind the chained souls on the top of a wall, much like a puppet show casts characters across the field of a wooden stage. So the chained souls can see shadows in front of them, or forms, projected to the wall in front of them off of the fire that blazes behind them which they cannot see. Hence these people know only shadows and forms their whole lives, although they believe this to be the one and only reality and source of truth for they know nothing else. Socrates then goes on to explain that a philosopher is like a person who is freed from this cave, and is let out into the light of the sun, where he sees and realizes that everything that he has thought to be real, has only been a shadow of truth and reality.[17]

Plato’s ethics and world view centered on this Theory of Forms, or Ideas as reflected by the allegory of the cave and his analogy of the divided line. His belief in the immortality of the soul and its superiority to the physical body, the idea that evil was a manifestation of the ignorance of truth, that only true knowledge can revealed by true virtue, all of these tenets stemmed from this idea that the abstract form or idea of a thing was a higher construct than the physical thing itself, and that the abstract Form of a thing was just as true and real, if not more so, that the concrete thing itself from which its Form manifested.

It is in the Timaeus however, one of the later and more mature works of Plato, that he expounds upon his view on the nature of the divine, the source of the known universe (cosmological view), as well as the role of the soul in nature. And although Plato, and Socrates as represented by Plato’s earlier works, rejected the mythological and anthropomorphic theology that was prevalent in Ancient Greece, Plato does not completely depart from the concept of a theological and divine or supra-natural creator of the known universe, at least as reflected in the words of Timaeus in the dialogue that bears his name.

In many respects, the ideas and postulates of the Timaeus represent an expansion on Plato’s Theory of Forms which he introduces in The Republic via his Allegory of the Cave. In the Timaeus, Plato makes a distinction between the physical world which is subject to change, and the eternal and changeless world which can only be apprehended by use of the mind and reason, i.e. is not perceivable by the senses directly. He also attempts to establish via a logical argument that the world and nature itself are the product of the intelligent design of some creator, and that mortals, given their limitations, can conceive only of that which is probable or “likely” and that the essential truth is perhaps unknowable. The passage itself in the Timaeus is profound enough to quote in full.

First then, in my judgment, we must make a distinction and ask, What is that which always is and has no becoming; and what is that which is always becoming and never is? That which is apprehended by intelligence and reason is always in the same state; but that which is conceived by opinion with the help of sensation and without reason, is always in a process of becoming and perishing and never really is. Now everything that becomes or is created must of necessity be created by some cause, for without a cause nothing can be created. The work of the creator, whenever he looks to the unchangeable and fashions the form and nature of his work after an unchangeable pattern, must necessarily be made fair and perfect; but when he looks to the created only, and uses a created pattern, it is not fair or perfect. Was the heaven then or the world, whether called by this or by any other more appropriate name-assuming the name, I am asking a question which has to be asked at the beginning of an enquiry about anything-was the world, I say, always in existence and without beginning? or created, and had it a beginning? Created, I reply, being visible and tangible and having a body, and therefore sensible; and all sensible things are apprehended by opinion and sense and are in a process of creation and created. Now that which is created must, as we affirm, of necessity be created by a cause. But the father and maker of all this universe is past finding out; and even if we found him, to tell of him to all men would be impossible. And there is still a question to be asked about him: Which of the patterns had the artificer in view when he made the world-the pattern of the unchangeable, or of that which is created? If the world be indeed fair and the artificer good, it is manifest that he must have looked to that which is eternal; but if what cannot be said without blasphemy is true, then to the created pattern. Every one will see that he must have looked to, the eternal; for the world is the fairest of creations and he is the best of causes. And having been created in this way, the world has been framed in the likeness of that which is apprehended by reason and mind and is unchangeable, and must therefore of necessity, if this is admitted, be a copy of something. Now it is all-important that the beginning of everything should be according to nature. And in speaking of the copy and the original we may assume that words are akin to the matter which they describe; when they relate to the lasting and permanent and intelligible, they ought to be lasting and unalterable, and, as far as their nature allows, irrefutable and immovable-nothing less. But when they express only the copy or likeness and not the eternal things themselves, they need only be likely and analogous to the real words. As being is to becoming, so is truth to belief. If then, Socrates, amid the many opinions about the gods and the generation of the universe, we are not able to give notions which are altogether and in every respect exact and consistent with one another, do not be surprised. Enough, if we adduce probabilities as likely as any others; for we must remember that I who am the speaker, and you who are the judges, are only mortal men, and we ought to accept the tale which is probable and enquire no further[18].

Plato then goes on, through the narrative of Timaeus in the dialogue, to describe the establishment of order by what he refers to as a divine craftsman, dêmiourgos, applying mathematical constructs onto the primordial chaos leveraging the four basic elements – earth, air, fire, and water – to generate the known universe, or kosmos. Note that the view espoused by Timaeus is that the world was not created by chance but by deliberate intent of the intellect, nous, as represented by the divine craftsman. Although one might conclude that this would imply Plato’s belief in an anthropomorphic principle of creation, akin to our Judeo-Christian God, there is no evidence that Plato would have been exposed to that theology as he lived some 4 or 5 centuries before Jesus and the Judaic theology was not nearly so wide spread in the centuries before Christ. Furthermore, one of Plato’s underlying premises for all of his work, is that the principles of reality or the known universe are most certainly worth exploring, again via dialogue and dialectic, but that absolute truth or knowledge is not something that he attempts to be putting forth, and in fact that absolute knowledge and facts are comprehensible by metaphor or analogy at best.

In the Timaeus, Plato attempts to describe the nature of the soul and its purpose within the context of this creative universe, describing the kosmos as the model for rational souls to emulate and try to understand, restoring the souls to their original state of balance and excellence. Therefore Plato, although clearly establishing the supremacy of reason and rationality in the search for truth and the nature of universe, as well as a mathematical and geometrical framework from which this demiurge crafted the world which permeates much of the Timaeus, did not completely abandon theology in his world view. Theology, in an anthropomorphic context, was the source from which the natural world was born in Plato’s view, even though he points directly to the fundamental unknowable nature of the universe, stating that we can only know what it is “like” rather than its true nature. Furthermore, by establishing the critical and comprehensive role of the soul, both of an individual and for the world at large, Plato rooted his ethical and moral framework within his cosmological narrative, i.e. a reason to be good that did not relay on a concept of an afterworld or hell as motivation.[19]

Plato’s most famous student by far was Aristotle, who is best known for his work on formalizing some of the basic principles of logic and reason, as well as a further development of the incorporation of mathematical concepts into philosophy and metaphysics among other things. He is also known for being the tutor for Alexander the Great, the great Greek empire builder of the 4th century BC, although the extent of the influence that he had on Alexander is debated by scholars[20].

The term metaphysics is first associated with Aristotle as the title of one of his works on the subject, although this was not a word that Aristotle used or titled any of his works himself, but was coined by later editors of his work who viewed the material in Metaphysics as that which came after (meta), or should be studied after, his work on Physics. Aristotle called the subject matter in question first philosophy or the study of that which defines that which is (specifically the term he uses is being qua being which as you can imagine is difficult to translate directly into English), but the term metaphysics has stuck over the centuries and has taken on to be a much more specific meaning in modern day usage as the fields of science, philosophy, biology, etc. have evolved into their own separate disciplines.

Just as Plato’s work covered much more than what is today considered philosophy, Aristotle’s extant literature explored many concepts outside of the realm of what we would classify as metaphysics or philosophy as well, topics such as biology, physics, logic, mathematics, and even geology. He also explored more in depth than Plato such concepts that relate to classical physics such as theories of motion and causation, setting the stage for centuries of analysis and thought which culminated in the branching off of science and empirical method from philosophy as reflected in the works of Descartes and Newton some two millennia later.

There are thirty-one surviving works that are attributed directly to Aristotle by modern scholars sometimes referred to as the Corpus Aristotelicum. Throughout these works, he refers to the variety of fields of research that he studies and writes about as epistêmai, or “sciences”. Although epistêmai is typically translated into English as “knowledge”, in the context of Aristotle’s work the word is classically translated to “science”, science in the broader and more modern sense of the term, e.g. the sciences. Note that It wasn’t until much later in history, not until the end of the Renaissance in the 17th and 18th centuries, that scientific method transformed what Aristotle deemed natural philosophy into an empirical activity whose basis derived from experimental results, thereafter distinguishing science from the rest of philosophy proper and the term science coming to mean those fields of knowledge and study that could be verified empirically by means of experimentation. Thereafter metaphysics denoted philosophical enquiry of a non-empirical character into the nature of existence.[21]

Although classification and grouping of Aristotle’s extant work is open to interpretation, for the most part it is agreed that Aristotle divided these “sciences”, into three basic categories, from which all of his philosophy and world view is structured. The first category, and the one of most interest to Charlie given the context of his inquiries into the historical development of theology and its divergence into philosophy and science proper, is what Aristotle refers to as the theoretical sciences, or what Aristotle calls first philosophy. Aristotle’s first philosophy includes his work in metaphysics, philosophy and theology, and also includes what he calls the natural sciences or natural philosophy which is reflected in his research and analysis in fields such as biology, astronomy, and what we would today call physics (e.g. the analysis of bodies of motion and their relationships in time and space) all of which have a more empirical basis as juxtaposed with his metaphysics which is purely theoretical in nature[22].

His second category of “science” he called practical science, which includes the analysis of human conduct and virtue and its effect on society at large, or ethics from both a personal and societal perspective. Much of his work in this area built off of the foundation provided by his teacher Plato, in his The Republic for example. The third classification or area of research of Aristotle was what he termed the productive sciences, which included exploration into such topics as rhetoric, agriculture, medicine and ship building as well as the arts of music, theater and dance[23].

Note that this broad range of topics that Aristotle explored, all of which he clearly felt strongly required further examination and analysis relative to the work of his predecessors, covered not only how the world is to be viewed or framed, with respect to identifying those qualities or attributes that described reality or being, i.e. his metaphysics, but also the foundations for society at large, ethics and virtue, as well as establishing the framework within which natural philosophy could be analyzed and explored, i.e. his elaboration and exploration of the principles of reason and logic which bled into geometry and mathematics. All of these fields of research were related from his perspective, just as they were by his predecessor Plato. One could not simply just create a logically framework for reality in and of itself, one needed to provide the framework for ethics and the relationship of the individual with the state and society within which he lived, and this connection needed to be well established in the metaphysical framework which described reality, and in turn mankind’s place in it. In other words, one must look at Aristotle’s extant work in toto to come to a complete understanding of how his metaphysics and world view related to his sociological and cosmological stances, for all the pieces of his metaphysical framework fit together.

In order to provide the theoretical and logical framework within which all of the sciences could be explored and established, Aristotle also authored many works on what we might call the basis of logic or reason. These constructs, which he expounds in his Categories, which provides his stratification of the building blocks of his metaphysical framework, as well as his treatises Prior Analytics and Topics where he delves deeply into the building blocks of analysis and reason itself, all fall into this category. His works in this area are typically categorized as the Organon, which comes from the Greek word for “tool”, signifying its foundational basis for the rest of Aristotle’s metaphysics and philosophy. In today’s nomenclature, these works could be loosely classified as the works which represent Aristotle’s epistemology, or the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature and scope of knowledge itself, or that which can be known.

His Category Theory, as it is typically referred to, is covered at length in The Categories. This basic framework of reality forms the foundation of his metaphysics so it’s important to have some idea as to what the different categories or the basis of reality are from his perspective, and what their relationship to each other is. The list of categories is meant to be exhaustive, in the sense that realistic construct must fall into one or more of the categories that he outlines and in turn anything that one would deem to be “real” must be able to be described through some articulation of its relationship to his Category Theory[24]. Aristotle divides the known world up into 10 different conceptual groups, the most important of which was his concept of substance, or ousia. These categories then provide the building blocks upon which all of his sciences, or epistêmai, are constructed. Below is an excerpt from Categories where he outlines not only what he considers to be his exhaustive list of “things” which are, or things which exist, but he also calls out the critical nature of that which is typically translated as substance, or ousia in Greek.

Of things said without combination, each signifies either: (i) a substance (ousia); (ii) a quantity; (iii) a quality; (iv) a relative; (v) where; (vi) when; (vii) being in a position; (viii) having; (ix) acting upon; or (x) a being affected. (Cat. 1b25–27)

All other things are either said-of primary substances, which are their subjects, or are in them as subjects. Hence, if there were no primary substances, it would be impossible for anything else to exist. (Cat. 2b5–6)

Translating ousia to “substance” in English does not express the full meaning of the term the way Aristotle intends however, and given the critical importance of this term in Aristotle’s metaphysics and philosophy, and in turn Aristotle’s influence on Western philosophy, science and metaphysics over the ensuing centuries, it is worth exploring this term ousia and how it’s relationship to its Latin derivative substantia or essentia, from which its English counterpart substance originates.

Ousia (οὐσία) is the Ancient Greek noun formed on the feminine present participle of εἶναι (to be); it is analogous to the English participle being, and the modern philosophy adjectival ontic. Ousia is often translated (sometimes incorrectly) to Latin as substantia and essentia, and to English as substance and essence; and (loosely) also as (contextually) the Latin word accident (sumbebekós).

Aristotle defined protai ousiai, or “primary substances”, in the Categories as that which is neither said of nor in any subject, e.g., “this human” in particular, or “this ox”. The genera in biology and other natural kinds are substances in a secondary sense, as universals, formally defined by the essential qualities of the primary substances; i.e., the individual members of those kinds.

Much later, Martin Heidegger said that the original meaning of the word ousia was lost in its translation to the Latin, and, subsequently, in its translation to modern languages. For him, ousia means Being, not substance, that is, not some thing or some being that “stood”(-stance) “under”(sub-).[25]

As shown above, the term ousia that Aristotle uses to describe the cornerstone of his metaphysics and world view is far from straight forward to translate into English, and the word “substance” does not really yield its true significance and much is lost in translation. From Charlie’s perspective this was a perfect example of the non-trivial task to try and translate some of these ancient esoteric ideas from Ancient Greece to the Indo-European, Romance languages in particular, languages that derived from the Latin translation of the Greek and then into the destination tongue, i.e. at least two transliterations away from the original source. This was true not only when attempting to translate some of the works of the Ancient Greek philosophers into English, but also when translating some of the extent Judeo-Christian literature into English which in many cases was also authored in Greek, or in many cases from an even more distant relative of English, Hebrew. To make matters worse, the Greek language itself was not necessarily designed to handle these esoteric and philosophical ideas that Aristotle, Plato and others were trying to articulate.[26]

Contrast this with the Indo-Aryan tradition who from earliest times had a language framework, namely Sanskrit, from which their esoteric and metaphysical, and of course theological, principles and constructs could be articulated to the reader. A reflection of this translation difficulty is that much of the Indo-Aryan philosophy, and many of the key terms that are used, are NOT in fact translated into the English when being described or conveyed to the modern reader, i.e. English has adopted some of the original Sanskrit terms for there is no English equivalent. The terms Atman and Brahman for example, and their relationship in the human body-mind construct as described by the chakras and Kundalini yoga, are all Sanskrit terms that represent core Vedic philosophical and theological constructs that have no English counterpart. These terms, and others such as Satchitananda, typically translated into English by modern Sanskrit and Vedic scholars as “Existence-Knowledge-Bliss-Absolute”, or even Samadhi, the state of emergence of the individual soul Atman into the essence of the source of all things or Brahman which is the eighth and final limb of the Yoga Sutras attributed to Patanjali, both are examples of esoteric terms that have a deep philosophical and psychological meaning in the Vedic tradition and have no direct English translation.

These Sanskrit terms, and many others, have made their way into the English language over the last century as Yoga has been introduced to the West as the most accurate way to describe these principles and to a great extent this provides for a better direct communication of their true underlying meaning. Samadhi has no English equivalent; the state which it refers to is best understood within the context of the Yoga Sutras within which it is described and the seven limbs that come before it, all of which also have their own Sanskrit counterparts and also have no direct English translation. Not so for the Greek and Judeo-Christian esoteric words that were used by the ancient philosophers and theologians, these words in almost all cases have been transliterated into English and in so doing have lost at the very least some of their meaning and context, and in some cases the original meaning intended by their original authors may have been lost altogether.

In many respects the best way to understand the underlying theology of Aristotle, or what scholars have later termed his teleology, or the postulate that some underlying final cause must exist in nature, is to contrast his metaphysical or theological beliefs with those of his teacher Plato, specifically as represented by the cosmology he outlines in his narrative in the Timaeus and his Theory of Forms as outlined in The Republic. For from Charlie’s perspective, it was not too much of a stretch to presume that it was the influence and works of his predecessor Plato that provided the impetus to Aristotle’s work and teaching, even if it was to establish his disagreement with his teacher.

Aristotle didn’t necessarily directly attack Plato’s belief in the existence of a divine creator per se, Plato’s demiurge, but he did argue, rightfully so from Charlie’s point of view, that Plato’s Theory of Forms lacked the sophistication to truly explain the totality of existence, or being qua being to use Aristotle’s terminology. That is to say, Plato’s Theory of Forms, despite being a powerful metaphor to describe the what he considered to be the underlying illusory nature of reality, the transformation and relationship of a Form or Idea into a thing which we would perceive as existing in and of itself is not fleshed out at all in Plato’s metaphysical framework. Aristotle’s metaphysics fleshed these concepts out in much more detail, and by providing the rational underpinnings of this more fleshed out Theory of Forms if you could call it that, he was able to build a rational and metaphysical framework that could extend not only the explanation of the underlying principles of ethics and virtue, but also to the world of natural philosophy, providing for the foundations of modern science as it were.

Although Aristotle’s theological beliefs are debated by modern scholars, it is certain that Aristotle disagreed with Plato’s cosmological and theological belief system in the sense that he believed that one must formulate a more rational underpinning for the explanation of reality, theological or otherwise, than what Plato puts forth in his body of work. Aristotle’s metaphysics, along with his work on defining logic and reason itself, represents a challenge to Plato’s belief, or faith as you might call it, that the underlying beauty of the world combined with the supremacy of Forms over the world of shadow as reflected by sensory perception as Plato describes in his Allegory of the Cave, is justification enough to establish the existence of an intelligent or divine creator, i.e. the demiurge or divine craftsman that Plato puts forth as the source of the kosmos.

In order to try and comprehend Aristotle’s cosmological or theological stance, you must not only comprehend his Category Theory, but also understand his causal framework for adequacy upon which his entire metaphysics rests. It is this framework, sometimes referred to as his four-causal explanatory scheme[27], that he describes the basis for all of his explanations of reality, or perhaps more aptly put, all things that which are said to exist. In other words, the existence of a thing, its substance, must be underpinned by his four-causal explanatory scheme in order to fully understand the attributes of a thing which exists. Although this may appear to be a metaphysical nuance at first, in this causal framework rests Aristotle’s fundamental metaphysical building blocks upon which any theological or teleological interpretation of his work must be viewed. He describes this causal framework quite explicitly in Physics:

One way in which cause is spoken of is that out of which a thing comes to be and which persists, e.g. the bronze of the statue, the silver of the bowl, and the genera of which the bronze and the silver are species.

In another way cause is spoken of as the form or the pattern, i.e. what is mentioned in the account (logos) belonging to the essence and its genera, e.g. the cause of an octave is a ratio of 2:1, or number more generally, as well as the parts mentioned in the account (logos).

Further, the primary source of the change and rest is spoken of as a cause, e.g. the man who deliberated is a cause, the father is the cause of the child, and generally the maker is the cause of what is made and what brings about change is a cause of what is changed.

Further, the end (telos) is spoken of as a cause. This is that for the sake of which (hou heneka) a thing is done, e.g. health is the cause of walking about. ‘Why is he walking about?’ We say: ‘To be healthy’— and, having said that, we think we have indicated the cause.[28]

From this we can gather that Aristotle’s causal metaphysical framework for reality is made up of four distinct but related causes, the second of which corresponds loosely to Plato’s Forms.

- the material cause of a thing or that from which a thing is made,

- the formal cause of a thing or the structure to which something is created (loosely corresponding to Plato’s idea of Forms or Ideas),

- the efficient cause of a thing which is the agent responsible for bringing something into being, and

- the final cause of a thing which represents the purpose by which a thing has come into existence.

Although it is open to debate whether or not Aristotle presupposes that all four causes must be present in order for a thing to exist (in fact in some cases he cites examples of which all four causes are not present but yet existence of said thing is still adequately explained[29]), this idea of a required efficient cause is unique to Aristotle relative to the philosophers that came before him and forms the basis upon which much of his theory of natural philosophy rests. This efficient cause of Aristotle can also be seen as representing the connecting principle of Plato’s concept of Forms to Plato’s illusory realm of the senses, representing the expansion of Plato’s metaphysics as reflected in the Theory of Forms rather than a complete abandonment of it[30].

Aristotle does not however, go so far as Plato as to believe in the existence of some divine, intelligent creator as being the source from which humans, or souls even, are born. It is clear however that from Aristotle’s point of view, there must be a final, or penultimate, cause in order to establish the firm existence of thing, or substance, in reality – at least in almost all cases. The complexity and importance of this issue of final cause is not lost on Aristotle, and he addresses the specific case of the explanation of the final cause of the natural world specifically in a subsequent passage in Physics, resting on the notion of formal cause as basis enough for the justification of a final cause in nature, as circular an argument as this may seem.

This is most obvious in the case of animals other than man: they make things using neither craft nor on the basis of inquiry nor by deliberation. This is in fact a source of puzzlement for those who wonder whether it is by reason or by some other faculty that these creatures work—spiders, ants and the like. Advancing bit by bit in this same direction it becomes apparent that even in plants features conducive to an end occur—leaves, for example, grow in order to provide shade for the fruit. If then it is both by nature and for an end that the swallow makes its nest and the spider its web, and plants grow leaves for the sake of the fruit and send their roots down rather than up for the sake of nourishment, it is plain that this kind of cause is operative in things which come to be and are by nature. And since nature is twofold, as matter and as form, the form is the end, and since all other things are for sake of the end, the form must be the cause in the sense of that for the sake of which. (Phys. 199a20–32)[31]

Aristotle’s metaphysics, or view of reality, then for the most part built off of the platform established by Plato’s Theory of Forms or Ideas, but Aristotle looked at the objective world perceived by our senses as more of an integrated manifestation of substance and its related attributes, combined with the notion of the prerequisite of his four-causal theory rather than espousing the material world as distinct and separate from the world of Forms, or in fact less real than the world of Forms and Ideas, as Plato espoused. This is a subtle distinction but an important one as what as what we find in subsequent philosophical and metaphysical systems after Aristotle (leaving aside theological and/or religious systems of belief as illustrated in Judaism, Christianity or Islam) is a departure of the conception of the world of the senses as simply a shadowy representation of true reality into a belief in the fundamental existence and reality of the objective world, the world of substance, a notion that has evolved into today what we might call materialism. To take this one step further, Charlie looked at Aristotle’s metaphysical constructs and belief system as the first step toward the departure of a theological conception of the basis of reality in the Western world.

So as the Greek society recognized and affirmed the role of the philosopher in society, due in no small part to the contributions of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, the branch of thought known as philosophy, as seen separate and apart from theology and religion, was born. And as this development occurred, the cosmological and mythological views of the ancients started to take a back seat to the more abstract constructs laid out by these ancient philosophers, leading at the very least to the introduction of a more rational and metaphysical foundation for theology and cosmology as well as providing a foundation for a more critical and scientific world-view as these new metaphysical frameworks started to become more widely accepted.

Reason, logic and mathematics then were all born at the same time as philosophy, and it required a civilization that allowed these ideas to reign freely, what we might call today freedom of speech, in order for these fields of knowledge and branches of thought to flourish and grow. If we are to believe the accounts of Plato and Xenophon, and Charlie saw no reason not to, Socrates gave his life in order to demonstrate his firm belief in the supremacy of truth, knowledge, wisdom, virtue, and the rule of law, over one’s own personal belief systems or blind faith in the mythological and cosmological constructs that underpinned Greek authority and politics in his day. With his execution then, and this was a critical step in the evolution of science from Charlie’s perspective, came the beginning of western man’s faith in the power of reason and mind over religious dogma and mythology.

So if we are to look for the birth of philosophy and metaphysics, and we are to believe Plato’s depiction of Socrates as reflected in the early dialogues of Plato, we must conclude that it is Socrates who established the supremacy of knowledge, truth and virtue over religion or theology, doctrines which had hitherto been questioned only at great peril. Socrates died, again if we are to believe Plato’s account of these events, in order to establish this new world order, or at least to create an environment in which these abstract ideas and constructs could be more freely explored.

In Plato’s Apology, where Socrates defends himself against the charges of “corrupting the young, and by not believing in the gods in whom the city believes”[32], Socrates tries to explain the meaning of the Delphic Oracle’s anointment of him as the most wise man in Athens, as well as explain the lengths to which he will go to establish the supremacy of wisdom over blind religious dogma.

This investigation has led to my having many enemies of the worst and most dangerous kind, and has given occasion also to many calumnies, and I am called wise, for my hearers always imagine that I myself possess the wisdom which I find wanting in others: but the truth is, O men of Athens, that god [theos] only is wise; and in this oracle he means to say that the wisdom of men is little or nothing; he is not speaking of Socrates, he is only using my name as an illustration, as if he said, He, O men, is the wisest, who, like Socrates, knows that his wisdom is in truth worth nothing. And so I go my way, obedient to the god, and make inquisition into the wisdom of anyone, whether citizen or stranger, who appears to be wise; and if he is not wise, then in vindication of the oracle I show him that he is not wise; and this occupation quite absorbs me, and I have no time to give either to any public matter of interest or to any concern of my own, but I am in utter poverty by reason of my devotion to the god.[33]

It was Plato then who carried on this tradition began by Socrates into the search for wisdom and truth for their own sake. Plato’s Academy was founded to train men in this art of the pursuit of knowledge, and teach its students the means by which these lofty ideals could be ascertained, as illustrated in his dialogues, all of which challenged the reader to look at various points of view of a certain topic or idea, and come to their own conclusions about the truth or what was right. Plato’s emphasis on dialectic, a rational tool that even Aristotle did not abandon, represented the cornerstone of Plato’s teachings from Charlie’s perspective, for it implied that reason and logic were more relevant and more important when trying to ascertain wisdom or truth. And it was within this framework of dialogue within which he presented his readers and students his metaphysical world view and its loosely coupled philosophical foundation, namely his Theory of Forms and his belief in the existence of some type of anthropomorphic God, not as indisputable facts of reality but as theses and hypotheses that were to be analyzed, thought through and molded by later students of his work.

It was Aristotle however, who spent decades learning from Plato and others in the Academy which Plato founded, who expounded upon Plato’s thin metaphysical framework and created a much richer and fleshed out rational foundation to describe the world around us, or that which could be considered real, along with the rational and mathematical building blocks with which the all subsequent branches of knowledge were to be constructed upon in the centuries to follow. And even though Aristotle’s theological beliefs are not explicitly stated anywhere in his work, it is safe to say that he does not anywhere put forth any specific theological stance or dogma, the absence of which could only have been by design. Furthermore, it is not too big of a leap of faith to state that Aristotle’s theology, or his faith if you will, rested in reason itself as the instrument from which truth and knowledge can be born.

[1] Note that in the Greek, there is no direct translation of the English monotheistic conception of God. Deus in Latin is the original etymological construct from which God originated.

[2] The delineation of a priesthood class survives to this day even in Hindu society, namely the Brahmin class of the Hindu caste system, albeit it in a less formal and strict form given the democratic form of government. See https://snowconesdiaries.com/2012/07/25/ancient-sumerian-cosmology-order-out-of-chaos/ for a look at Sumer-Babylonian ties between cosmological beliefs and authority and https://snowconesdiaries.com/2012/07/21/the-cosmology-of-the-egyptians-religion-and-power/ for a review of the connection between the priestly class of the Egyptians, namely the pharaohs, and their cosmological or religious system of beliefs.

[3] From Cicero, Tusculan Disputations, 5.3.8–9.

[4] Sophists were known for teaching debate and rhetoric along with what we would consider today to be philosophy in exchange for money, and therefore eventually became associated with the bending of truth and argument for political or other personal gain: hence the modern day definition of sophism which implies the use of argument with some level of underlying deceit and cunning. Although Socrates was reputed to have been taught by several sophists, he later shunned their methods as exclusive and unethical. Prominent Sophists in Ancient Greece include Protagoras (490-420 BCE) from Abdera in Thrace, Gorgias (487-376 BCE) from Leontini in Sicily, Hippias (485-415 BCE) from Elis in the Peloponnesos, and Prodicus (465-390 BCE) from the island of Ceos.

[5] Although you could argue that the notion that all of reality was related to and underpinned by mathematics and numbers was first propagated by Pythagoras, given his place in history and the lack of first-hand accounts regarding his theological and philosophical teachings however, there is not much direct evidence that points to this as an immutable fact. It is safe to say assume however, citing references to Pythagoras by Plato and Aristotle among others, that many of his ideas influenced Socrates and in turn Plato and therefore through Pythagoras has had at the very least an indirect influence on the development of reason and science in Western civilization.

[6] References to these pre-Socratic philosophers and their work comes from the extant literature of of Aristotle, Plutarch, Diogenes Laërtius, Stobaeus and Simplicius, as well as from early theologians, especially Clement of Alexandria and Hippolytus of Rome.

[7] Pythagoras, Thales of Miletus, Heraclitus, Xenophanes, Parmenides, Zeno, Empedocles, Anaxagoras, Leucippus, and Democritus all made contributions to pre-Socratic philosophy thought and were referenced by later philosophers and historians to some extent or another.

[8] Socrates plays a significant role in Aristophanes Clouds, a satirical play of the sophist and philosophical traditions of late 5th century BC Athens. He is primarily depicted as a bit of a buffoon in the play, but if nothing else it reflects the broad cultural and socio-political impact that the philosophical and sophist traditions of his day, Socrates and Plato reflecting the most prominent school, and therefore the easiest targets to be made light of.

[9] Plato lived and wrote in the latter part of the 4th and early part of the third century BC (circa 424 to 327 BC), and in his later life founded the Academy of Athens, the first known institution of higher learning in the Western world that persisted until the beginning of the first century BC, the same Academy from which Aristotle was schooled. Thirty-six dialogues have been ascribed to Plato, and they cover a range of topics such as love, virtue, ethics, and the role of the philosopher in society.

[10] The Republic (Greek: Πολιτεία, Politeia) is a Socratic dialogue written by Plato around 380 BC concerning the definition of justice and the order and character of the just city-state and the just man. The work’s date has been much debated but is generally accepted to have been authored sometime during the Peloponnesian War which took place between Athens and Sparta at the end of the 5th century BC (circa 431 to 404 BC). The Republic is arguably Plato’s best-known work and has proven to be one of the most intellectually and historically influential works of philosophy and political theory since the dawn of civilized man. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Republic_(Plato) for more detail.

[11] The Politics of Aristotle, trans. Benjamin Jowett (London: Colonial Press, 1900).

[12] A. N. Whitehead, Process and Reality, p. 39

[13] Dialectic is a form of intellectual pursuit and authorship reflected in a dialogue between two or more persons where various positions on the topic in question are posited and rationally expounded upon, a yielding of the truth via reason and logic where both sides of an argument are explored and stood behind by individuals, be they fictitious or real persons. This is the basic structure of Plato’s Socratic Dialogues, a selection of works authored by Plato and Xenophon, the other prominent disciple of Socrates, being so categorized because Socrates is a characterized in the work not due to the content of the dialogues themselves.

[14] The exception to this would be Plato’s Apology which by all accounts is Plato’s attempt to describe the actual events of Socrates trial and Socrates’s actual defense and to a lesser extent the Crito which is Plato’s description of the final conversation between Crito and Socrates concerning justice where Crito attempts to convince Socrates, unsuccessfully, that he should flee his cell and Athens to avoid his impending execution.

[15] Plato, The Republic, Book 6, translated by Benjamin Jowett.

[16] Also sometimes referred to as the Analogy of the Cave, Plato’s Cave, or the Parable of the Cave.

[17] In its simplest interpretation, the allegory of the cave can be viewed as outlining and defining Plato’s belief in the supremacy of forms or ideas over knowledge derived from sensory perception or the material world, i.e. his theory of forms[17], and taken one step further can be interpreted to mean that Plato is espousing a doctrine of the illusory nature of reality much like the Vedic tradition and its concept of Maya.

[18] Benjamin Jowett translation. From http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/timaeus.html.

[19] For a more comprehensive look at the Plato’s Timaeus and its import, see the Stanford Encyclopedia entry, Plato’s Timaeus, which can be found at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/plato-timaeus/.

[20] Aristotle is known to have been Alexander’s tutor for at least two years, from when Alexander was 13 to 15, but then Alexander was commissioned to the Macedonian army and therefore any later influence by Aristotle is brought into question.

[21] The branch of philosophy called Epistemology stems from the same root as epistêmai, i.e. meaning “knowledge” or “understanding” combined with logos, meaning “study of”. This field of study is concerned with the nature and scope of knowledge itself, and arguably is the best description of Aristotle’s work in toto. Epistemology questions what knowledge is, how it is acquired, and to what extent it is possible for a given subject or entity to be known. The term was introduced by the Scottish philosopher James Frederick Ferrier (1808–1864) and the field is sometimes referred to as the theory of knowledge. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epistemology for more details.

[22] ‘Prior to the modern history of science, scientific questions were addressed as a part of metaphysics known as natural philosophy. The term science itself meant “knowledge” of, originating from epistemology. The scientific method, however, transformed natural philosophy into an empirical activity deriving from experiment unlike the rest of philosophy. By the end of the 18th century, it had begun to be called “science” to distinguish it from philosophy. Thereafter, metaphysics denoted philosophical enquiry of a non-empirical character into the nature of existence. Some philosophers of science, such as the neo-positivists, say that natural science rejects the study of metaphysics, while other philosophers of science strongly disagree.’ From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metaphysics.

[23] There are a variety of ways to categorize Aristotle’s extant works but this categorization seems most intuitive and is taken from the Standard Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Aristotle.

[24] Note that despite the critical role that Aristotle’s Category Theory plays in his metaphysics and world view, he does not anywhere describe the rational foundation as to why the world should be broken up into the ten categories that outlines. This of course leaves much of his metaphysics open to criticism by later scholars and interpreters of his work given the lack of rational underpinning for such a critical metaphysical construct that permeates virtually all of his extant literature.

[25] From Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ousia.

[26] A classic Judeo-Christian example of this transliteration problem can be found in the Gospel According to John, or simply John, the fourth of the Canonical Gospels of the New Testament and the Gospel unique to the other three Synoptic Gospels in many respects. The oldest extant examples of the John were authored in Greek, and in particular the opening verse which is classically translated into English as “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.”

[27] As outlined in the Standard Encyclopedia of Philosophy’s interpretation of Aristotle’s work in Aristotle, http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle/.

[28] Physics 194b23–35 as taken from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Aristotle at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle/.

[29] See Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Aristotle at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle/ pages 41-43 for a more detailed description of Aristotle’s view on the necessary and sufficient attributes of his four causal theory.

[30] It is however, very clear that Aristotle most definitely deviates from Plato’s view that the world of Forms is real and the world of the senses is simply illusory, which does in fact represent a significant divergence from Plato in his world view of reality akin to the dualistic view of reality in the Vedic philosophical tradition.

[31] From the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Aristotle. Found at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle/.

[32] Plato’s Apology (24b). Apology in this context coming from the Greek meaning “defense” or “explanation”.

[33] From Plato’s Apology. Jowett’s translation at http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/apology.html.

Thanks. More coming. Next post will be on Western philosophical development from Plato down through the Middle Ages up until the Renaissance. Work in progress but coming soon.

I entered your site while I was searching cartilage earrings

and I admit that I am very lucky for doing so. I think that this is a extremely cute blog you have here.

Would it bother you if I shared site on FB along with your url and

title of the page:”Socrates, Plato and Aristotle: First Philosophy “??

Regards!

The Piercings for Cartilage Group

That would be fine. Thanks.

I realize it is more utnnrsnaedidg a subject by parallel study with historical approach, for example ” Buddhism, A journey of 2500 years” by U Aunt Maung (M.A) Bombay that give background scenario, various trends of beliefs in India, in which we learn the rise and fall of religion. I noted Sayagyi U Shwe Aung and U Aunt Maung were contemporaries and probably studied in India same time. I prefer their presentations and quotations. Last, Saya Sonata and well wishers, thank to all of you for comprehensive post and heartfelt comments.

I realize it is more utisrenanddng a subject by parallel study with historical approach, for example ” Buddhism, A journey of 2500 years” by U Aunt Maung (M.A) Bombay that give background scenario, various trends of beliefs in India, in which we learn the rise and fall of religion. I noted Sayagyi U Shwe Aung and U Aunt Maung were contemporaries and probably studied in India same time. I prefer their presentations and quotations. Last, Saya Sonata and well wishers, thank to all of you for comprehensive post and heartfelt comments.