Ancient Chinese Theology: From Shàngdì to Tiān

The Chinese civilization is if not the, then certainly one of, the oldest persistent civilizations on the planet.[1] Its roots go back to the early part of the second millennium BCE with the first dynastic empire, the Xia Dynasty (circa c. 2070 – c. 1600 BC) was established by Yu the Great in the Yellow River valley basin of northeastern China. The Xia Dynasty was succeeded by the Shāng Dynasty (circa 1600 BCE to 1046 BCE) and is contemporaneous with what modern historians call “Bronze Age China” given the proliferation of Bronze that is found in the archaeological record during this time. It is during the Shāng Dynasty period that we see the first evidence of writing in ancient China, on bone inscriptions and is from this time period that the worship of Shàngdì dominates the theological landscape. Some of the earliest elements of Chinese civilization can be found from the Shāng Dynasty era, both from the (limited) written and more extensive archeological evidence from this time period, along with the historical information we gather from later historians and literature that compiled later during the Zhou, Qin and Han Dynasties in the first millennium BCE

Much of what we know about the Shāng Dynasty comes from not only archeological records, which include some of the earliest written inscriptions we have from ancient China, i.e. Oracle bone inscriptions[2], but also from ancient Chinese texts written in Classical Chinese, or “Literary Chinese” (文言文 or wényán wén, which means “literary language writing”), a written form of the Old Chinese language.[3] These texts were compiled in the Zhou, Qin and Han dynastic periods of Chinese antiquity – latter part of the first millennium BCE – during which time much of the classic Chinese literature from antiquity took its present form and during the same time period more or less that “philosophy” emerged and was codified in both the Indian subcontinent as well as throughout the Mediterranean in the region of Hellenic influence.

Figure 11: Theo-Philosophical Development in Ancient China

The two most important historical texts from this period are the Book of Documents, or the Shujing), also called the Classic of History which is one of the Five Classics of ancient Chinese literature as well as the Records of the Grand Historian, or Shiji, which was written by Sima Tan (c. 165 BCE – 110 BCE) and his son Sīmǎ Qiān[4], both Han court astrologers at the turn of the second century BCE. The Records of the Grand Historian is a Herodotus Histories like text chronicling the history of China from the time of the pseudo-mythical Yellow Emperor, or Huangdi, to the Han Emperor Wu who was the reigning Emperor when the book was completed in 109 BCE.

From the material in these historical texts, and consistent with what we know about the Shāng Dynasty culture of ancient China from the archeological record, we see the importance of ritual and ceremony and the veneration of ancestors as important socio-theological constructs, hence the purpose behind the creation of such historical narratives to begin with which document the birth of Chinese civilization in the Yellow River basin and document the great deeds of their ancestors starting with Yu the Great (大禹 or Dà Yǔ, c. 2200 – 2101 BC), the tamer of the Great Flood who is the founder of the Xia Dynasty and renowned as a ruler of upstanding moral and ethical character, a philosopher king in the true sense of the term as espoused in Plato’s Republic.

It’s during this transition from the more archaic and prehistoric period of Shang dynastic influence – which was characterized theologically speaking by the worship of Shàngdì as the pre-eminent and all pervasive governor and presider over the universe and the affairs of men – to the influence of the somewhat more civilized and analytical culture that characterizes the Zhou Dynasty period of Chinese antiquity, that we see the introduction and ultimate replacement of the sacrificial worship of Shàngdì with the more theo-philosophical notion of “Heaven”, or Tiān (天) which is looked to as the benchmark of moral integrity as well as the ultimate authority upon which the governing class rests. We see this transition happening quite distinctly early in the Zhou Dynasty period as the early Zhou dynastic rulers appeal directly to the “Mandate of Heaven” to justify their overthrow of the Shāng Dynasty and establish themselves as rulers of the Chinese empire.

It is during the Zhou Dynasty period that we see the creation, evolution and proliferation of a multitude various different philosophical schools – the so called “Hundred Schools of Thought”, (諸子百家 orzhūzǐ bǎijiā) which flourished during what is referred to by modern Chinese historians as the Spring and Autumn period (c. beginning of the 8th to the end of the 5th century BCE) through the so called “Warring States Period” which culminates in the consolidation of power amongst the warring states in ancient China by the founder of the Qin Dynasty in 221 BCE.[5] During this time the intellectual elite, or scribes, were employed by the various political factions to advise them on matters of state as well as compile theo-philosophical works that were intended to not only legitimize their authority but also to systematize and document various schools of theo-philosophical thought. From the Shiji, the Records of the Grand Historian, the six main competing theo-philosophical schools of this period were Confucianism, Legalism, Daoism, Mohism, School of Yīn-Yáng, and the School of Names (or Logicians).[6]

Toward the end of the first millennium BCE, most of the ancient Chinese classics which we know today became standardized, and several were adopted as “official” literary documents of the Chinese state during the Western Han, or Former Han period (206 BCE – 9 CE) – namely the Classic of Poetry (Shijing), the Book of Documents (Shujing), the Book of Rites (Liji), the Book of Changes (Yìjīng), and the Spring and Autumn Annals (Chūnqiū), each of which became integrated into the core state sponsored academic curriculum and have been used up until modern times as not only history teaching texts but as moral and ethical guiding works as well.

At the same time, Confucianism is adopted by the Han Dynasty rulers as the official state ideology and therefore we begin to see a very strong influence of Confucian thought not only in the socio-political sphere, but also in ethical philosophy as well as theology and divination practices which were very closely connected as outlined in the Yìjīng. “Heaven” was seen not only on as guiding principle and ultimate authority upon which their theology was based, but also as the guiding principle upon which the emperors and ruling classes of ancient China were to base their decisions, and ultimately upon which their authority – as seen again through the Mandate of Heaven – rested upon. Heaven, as both a material and ever present physical construct as reflected in the heavens themselves, as well as a more ethereal and philosophical concept reflecting the underlying order and law of the universe which manifested in the material and socio-political spheres as well, was looked upon as the standard bearer for not only ethics and morality for individuals, but also as the guiding principle behind the governance of society and politics.

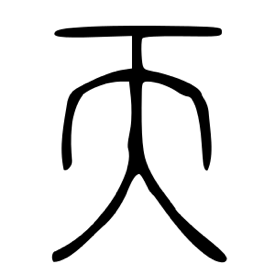

The Traditional Chinese character for Tiān is “天”, which can be traced back through Seal script, Bronze script and even as far back to Oracle bone inscriptions from pre-historic China from the second millennium BCE, is closely related to the Traditional Chinese character for “man”, or “person” (rén, “人”). Essentially the character for Tiān seems to have evolved from the glyph for man, to which strokes were added to illustrate the magnificence and ultimate superiority of Tiān over all the other anthropomorphic deities as well as all mankind as well of course, ultimately evolving into the Traditional Chinese character “天”.

Figure 12: Evolution of Chinese character for Tiān or “heaven”[7]

Figure 12: Evolution of Chinese character for Tiān or “heaven”[7]

The fact that the character for Tiān can be traced back through the archeological record to illustrate its relationship to the character for “man” betrays the anthropomorphic aspect of Tiān/Shàngdì which must have been predominant in pre Zhou Dynastic China.[8] So while the anthropomorphic qualities of Tiān are smoothed over as it were by the time of the classical era of Chinese philosophical antiquity, i.e. when Confucian philosophy becomes the predominant tradition throughout ancient China, we can see the direct reference of the idea, the concept, of an all pervading anthropomorphic deity, i.e. Shàngdì, reaching at least as far back as the Shāng Dynasty (2nd millennium BCE).[9]

In the time of the Zhou Dynasty at the turn of the first millennium BCE, we see a transition and semantic equivalence that is established between Shàngdì and Tiān, or Heaven, which is also the word for “sky”. Tiān becomes one of the three pillars of the world order in classical Chinese philosophy – Heaven, Earth and Man. We see this transition take place, along with the evolution of Classical Chinese as a writing system, first in the Zhou Dynasty period and then maturing in the latter half of the first millennium BCE in the Warring States Period, being firmly established in Chinese philosophical nomenclature by the beginning of the Han Dynasty in 202 BCE (Former or Earlier Han) when most if not all of classical Chinese philosophical works were standardized and “canonized” so to speak.

We see the role of heaven played out in the socio-political sphere as well beginning with the Zhou Dynasty specifically which Confucius looked upon as a bygone age of justice and virtue. It’s in the transitional period between the Shang and Zhou dynasty that we find the first reference to the notion of the “Mandate of Heaven” which was used by the first dynastic rulers of the Zhou as justification for the overthrow the Shang dynastic rulers. This idea that the emperor of China gets his authority from Heaven which bestows a right to rule on a just ruler or “Son of Heaven”, i.e. Tianzi, is somewhat unique to the Chinese and has been leveraged by emperors in Chinese antiquity after the Zhou Dynasty to justify an overthrow of an emperor or a dynasty. Natural disasters, unrest or famine were for example generally considered to be signs that the rulers had lost the Mandate of Heaven and so the well-being of the ruled and the authority of the ruler were seen as tightly interconnected and interdependent upon each other.

One of the unique attributes of the Chinese philosophical tradition is its lack of focus on what we would call in the West theological concerns, i.e. issues related to how the universe was created (cosmogony or theogony) and what divine forces if any preside over it. While even in the philosophical works of Plato and Aristotle we find a rejection, or at least a lack of consideration, of mythology and the realm of the gods, in favor of underlying principles which drive creation which have a more “rational” foundation – i.e. Aristotle’s prime mover and Plato’s Demiurge. This is the classic Logos over mythos transition that takes place quite unique to the Mediterranean and is a marked characteristic of the Hellenic philosophers.

In the ancient Far East however, the region which eventually became what we know today as China, while we find an implicit theological principle in the idea of “Heaven” (Tiān), we do not see it dealt with specifically or directly in the works of the philosophers themselves like we do with Plato’s Demiurge or Aristotle’s prime mover. It is more of a fundamental backdrop of existence and divine “order”, which is looked upon as a benchmark, an example as it were, of ethics and morality, of social governance, and as a living “being” or “entity” which can be queried to assist in practical matters of state as reflected in the yarrow stalk divination rituals surrounding the Yìjīng. In other words, in the Far East the existence of an anthropomorphic god who creates and maintains the universal order is not analyzed or documented in the early theo-philosophical tradition as it were, it is simply presumed and looked to as a guiding principle for the life of the individual, and within the socio-political sphere of life.

In general, Heaven to the ancient Chinese takes on the form of what we in modern parlance would call a more naturalist view of divinity, in particular as the Chinese philosophical systems evolve and are compiled and documented in the classical period of Chinese antiquity from the second half of the first millennium BCE onwards. Implicit in all the classical philosophical works from Chinese antiquity is a belief in the tri-partite universal order based upon the interworkings and relationships of the realm of Heaven (Tiān 天), the realm of Earth (Di 地), and the realm of Man. It could be said that the whole of Chinese philosophy is meant to, and produced for, the establishment of harmony between these three interconnected yet distinct aspects of reality.

From the Yìjīng), the Book of Changes, one of if not the cornerstone Chinese philosophical text from antiquity, the core of which was written and used as a divination text from the late Shang and early Zhou periods, we find the predominance of the notion that the purpose of life, and in fact Fate itself, is best understood as the harmonization and balance of the forces of change (yi) as reflected through the understanding of the workings of material and spiritual universe which are intellectually and metaphysically delineated across three separate but related conceptual frameworks – those of Heaven, Man and Earth.

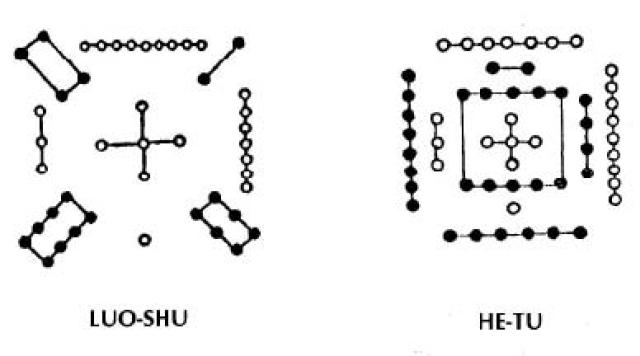

In the Yìjīng, and in the bāguà (eight trigrams), each of these respective world orders was represented by an individual broken line representing Yīn (receptive, dark, female) or a solid line representing Yáng (creative, light, male), which when brought together in the trigram arrangements (again eight of them, i.e. the bāguà) were read from the bottom up, with the bottom symbol representing the domain of Earth, the middle symbol the domain of Man, and top most symbol the domain of Heaven. These trigrams were combined together, two of them, to form the 64 hexagrams which constitute the core of the Yìjīng, where in the hexagram structure the bottom two lines represented the world of Earth, the middle two lines represented the world of Man, and the top two lines represented the world of Heaven, where each hexagram symbolized a specific state of being, or aspect of change (yi), which was to be interpreted given the current context of the consultation of the text, i.e. the divination process.[10]

From the Great Commentary, one of the most prominent of the Ten Wings treatises that expounds upon the underlying metaphysics and philosophy underlying the Book of Changes, we find the work described specifically as, “… vast and far-ranging, and has everything complete within it. It contains the way of the heavens, the way of human beings, and the way of the earth”.[11]

The Book of Changes contains the measure of heaven and earth; therefore it enables us to comprehend the tao of heaven and earth and its order.

Looking upward, we contemplate with its help the signs in the heavens; looking down, we examine the lines of the earth. Thus we come to know the circumstances of the dark and the light. Going back to the beginnings of things and pursuing them to the end, we come to know the lessons of birth and of death. The union seed and power produces all things; the escape of the soul brings about change. Through this we come to know the conditions of outgoing and returning spirits.

Since in this way man comes to resemble heaven and earth, he is not in conflict with them. His wisdom embraces all things, and his tao brings order into the whole world; therefore he does not err. He is active everywhere but does not let himself be carried away. He rejoices in heaven and has knowledge of fate, therefore he is care free. He is content with his circumstances and genuine in his kindness, therefore he can practice love.

In it are included the forms and scope of everything in the heavens and on earth, so that nothing escapes it. In it all things everywhere are completed, so that none is missing. Therefore by means of it we can penetrate the tao of day and night, and so understand it. Therefore the spirit is bound to no one place, not the Book of Changes to any one form.[12]

While these excerpts no doubt represent later interpretations of the significance of the text, at least later than when the text was initially drafted and used which goes at least as far back as the Zhou Dynasty (early first millennium BCE) and probably much earlier, we see implicit here the fundamental belief in the cosmological world order being broken into three disparate and yet at the same time interconnected aspects, i.e. the world order of Heaven, Earth and Man.

The totality of possible states of existence of these three aspects of the universal order, as well as the notion of change (yi) which was believed to be the elemental property of existence, being itself, is reflected in the 64 hexagrams underlying the Yìjīng, the proper understanding of which, when combined with the yarrow stalk divination process itself, would yield understanding of the true nature of a given situation through which a proper and optimal “decision” could be made which lended itself toward greater tranquility, harmony and balance rather than disharmony, chaos and confusion.

In the Analects, a Confucian text authored during the Warring States Period (4th/3rd centuries BCE), we find references to Heaven spread throughout the text, not necessarily representing a core philosophical principle per se, but yet at the same time representing a fundamental force in the universe, a force of good, that cannot be ignored and which needs to be properly understood in order to lead a moral and true life, the basis of which led to happiness and psychic and emotional harmony and balance.

The Master said, “Without recognizing the ordinances of Heaven, it is impossible to be a superior man. Without an acquaintance with the rules of Propriety, it is impossible for the character to be established. Without knowing the force of words, it is impossible to know men.”[13]

The “ordinances of Heaven” here refer to the classic Confucian ideals of propriety and ritual (lǐ) which hearken back to early Zhou Dynasty rituals and customs to which Confucian philosophy looked upon as a period of moral and ethical virtue, in particular within the context of the Warring States Period of Chinese antiquity. To Confucius, these ancient customs and rituals formed the fabric of a well-functioning society and were directly linked, integrally tied to, the proper balance and harmony of the world of Heaven and the world of Man.

Also from the Analects we find:

The Master was put in fear in Kuang. He said, “After the death of King Wen, was not the cause of truth lodged here in me? If Heaven had wished to let this cause of truth perish, then I, a future mortal, should not have got such a relation to that cause. While Heaven does not let the cause of truth perish, what can the people of Kuang do to me?”[14]

Heaven to Confucius also represents an ever-present force of nature that cannot be deceived, and one who guides people’s lives and maintains a personal relationship with them, one who has instilled various qualities, like virtue for example, in Confucius himself, and even in some cases dolling out tasks for people to fulfill in order to teach them of virtue and morality, i.e. ethics. The order of the world according to Confucius is established and overseen by Heaven, it was the source of all truth and knowledge. Much of the notion of Heaven as established by Confucius in the Analects and other later Confucian philosophical works, of which the Yìjīng ultimately comes to be known as, lends itself to the sense of naturalism that the ancient Chinese theo-philosophical systems are known for.

Similarly, Mohism (or the “School of Mo”) which was one of the competing philosophical schools of Confucianism during the classical period, appealed to Heaven as the ultimate guiding post for moral and ethical behavior, contrasting their system of ethics and governing to the ancestor worship and veneration that played such a prominent role in the Confucian teachings. Despite Mozi’s more practical bent, the school attributed to him nonetheless still looked to Heaven as the guidepost to moral and ethical behavior.

Mohism, founded by Mozi (or Mo Tzu, c 470 BCE to 391 BCE), took root in ancient China around the same time as Confucianism in the second half of the first millennium BCE. While initially it clearly had some strong socio-political support particularly during the Warring States Period, never got an imperial in later Chinese dynasties in particular after unification with the Qin Dynasty in the third century BCE.

Now, what does Heaven desire and what does it abominate? Heaven desires righteousness and abominates unrighteousness. Therefore, in leading the people in the world to engage in doing righteousness I should be doing what Heaven desires. When I do what Heaven desires, Heaven will also do what I desire. Now, what do I desire and what do I abominate? I desire blessings and emoluments, and abominate calamities and misfortunes. When I do not do what Heaven desires, neither will Heaven do what I desire. Then I should be leading the people into calamities and misfortunes. But how do we know Heaven desires righteousness and abominates unrighteousness? For, with righteousness the world lives and without it the world dies; with it the world becomes rich and without it the world becomes poor; with it the world becomes orderly and without it the world becomes chaotic. And if Heaven likes to have the world live and dislikes to have it die, likes to have it rich and dislikes to have it poor, and likes to have it orderly and dislikes to have it disorderly. Therefore we know Heaven desires righteousness and abominates unrighteousness.[15]

Here we see Heaven being represented as not only having a direct role in the proper harmonious functioning of the cosmos and natural, material world of nature, but also very specifically as applied to the affairs of men as the guiding principle to morality and ethics. While it might be a little far fetched to tie any anthropomorphic attributes to the Heaven which Mozi appeals to, we still find a very well developed theo-philosophical concept here which in some sense is presumed to have will and desire of its own, and reflects and embodies so to speak, a notion of fairness and justice much like the Platonic and Aristotelian sense of virtue, i.e. arête.

A more anthropomorphic sense of Heaven can be found in Mozi’s work Will of Heaven, language which reflects again not only the source of morality and ethics in human behavior, but also the source of order, balance and harmony for the material universe as well, all of which come to form the core theo-philosophical construct in ancient Chinese theo-philosophy in all its forms.

I know Heaven loves men dearly not without reason. Heaven ordered the sun, the moon, and the stars to enlighten and guide them. Heaven ordained the four seasons, Spring, Autumn, Winter, and Summer, to regulate them. Heaven sent down snow, frost, rain, and dew to grow the five grains and flax and silk that so the people could use and enjoy them. Heaven established the hills and rivers, ravines and valleys, and arranged many things to minister to man’s good or bring him evil. He appointed the dukes and lords to reward the virtuous and punish the wicked, and to gather metal and wood, birds and beasts, and to engage in cultivating the five grains and flax and silk to provide for the people’s food and clothing. This has been so from antiquity to the present.[16]

Here we see the Mohist tradition look to Heaven and its semblance of order, even justice, as the proposed bedrock of their moral and ethical system. While it may be a stretch to call this some form of ancient monotheism, the parallels between this Heaven and the Yahweh of the Jews which Christianity and then Islam later adopted is somewhat striking. To this end the Way (Dao), as reflected in the Will of Heaven (Tianzhi, Tiān “Heaven” + zhi “Will”), and the importance of “right” and “correct” moral and ethical behavior in both everyday life as well in the sphere of governance as understood through the proper understanding of the notion of Heaven itself, become the dominant themes of early Chinese theo-philosophical.

Whether in early Daoist sources (the dao of Heaven) as reflected in the Yìjīng, or in the more ethical and moralistic schools represented by Confucian and Mohist doctrines as noted above, each of the schools rested their doctrines in no small measure on the fundamental belief that Heaven not only existed, but that it also operated according to a moral and ethical rule or law which should be emulated and followed by man, and the society at large, to promote peace and harmony. While this principle represents a significant evolution and deviation from the worship and ritual sacrifices offered to Shàngdì from the Shāng Dynasty that presumably was practiced in pre-historical China as well, the semantic equivalence which was tied to this ancient god of the sky and Heaven in the more abstract sense clearly share a common ancestry.

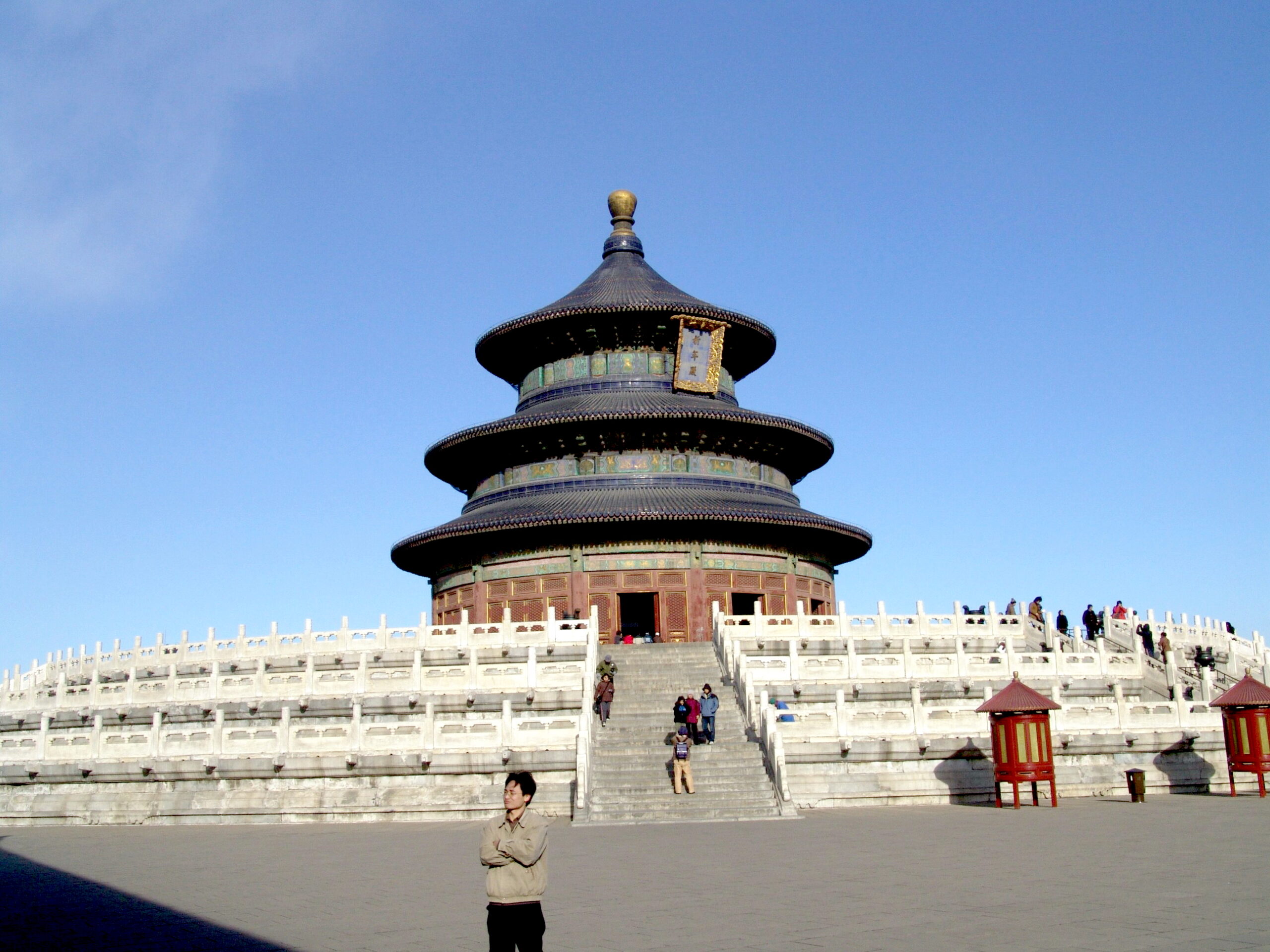

So this worldview of the tripartite order of Heaven, Earth and Man which is meant to operate in harmony and balance that the sages (shamans really from early Chinese pre-history) attempted to align in the individual and social fabric via the use of divination texts like the Yìjīng which in its original form is referred to as the Zhōu Yì prior to the addition of the Ten Wings in the last half of the first millennium BCE. The system of belief that is encoded in the Yìjīng which became one of the Five Confucian Classics which underpinned all of ancient Chinese theo-philosophy, clearly reflected and evolved from a much older theological belief system that was based upon the worship of Shàngdì through elaborate rituals and sacrifice, practices which continued to persist in some form or another even up until the 20th century in China. The underlying philosophy and ritual of divination which was encoded in the structure and practices surrounding the Yìjīng, evolved and emerged out of this ancient worship of Shàngdì and was based upon the fundamental belief in the existence of Heaven as a guiding principle of balance, harmony, ethics and virtue in not just the sphere of Heaven, but the sphere of Earth and Man as well.

Parallels to this worship of a supreme god of the sky existed in the West in antiquity as well, in the cosmological and mythical traditions of the Ancient Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, Jews, and even Indo-Aryan peoples, each who worshipped their own versions of a sky god as one of the primary forces of nature that was established at the very beginning of the creation of the cosmos. No doubt this reverence for the “god” of the sky, a personification and system of worship for that mysterious realm of the heavens, reflected the beliefs of the ancient hunter-gather shamans and priests that held this realm, and the being that presided over it, as the supreme ruler and governor over the universe. The ordering and movement of the stars, sun and moon, and the underlying belief that these movements and events (eclipses, comets, full moons, passage of the seasons, movement of the sun and moon throughout the ecliptic, etc.) dictated and had a profound influence on human affairs, essentially what we refer to as astrology today, is consistent across all ancient civilizations. The ancients of course had a much closer relationship, and reliance on, the celestial sphere than that of “civilized” man. In some sense, like the Epicureans to the West it could be argued that Confucius held that the world of spirits and the gods, i.e. shén, was too difficult to comprehend and therefore the mind or intellect should be focused on more practical measures – like for example how best to live, behave and govern and which social norms could be established for the good of all society. But this “spirit” world, the world of the gods to the West, was encapsulated in the notion of Heaven from early Chinese theo-philosophy, not altogether denied existence, it simply took a back seat to what were considered more important and practical topics such as how to live and how to govern.

While there are clearly some differences in terms of the characteristics or properties of Shàngdì and its later formation into the more philosophical construct Heaven and the Judeo-Christian concept of God for example. The “Heaven” that we see in the classical Chinese texts is far removed from the sky and heaven god of the ancient Chinese pantheistic traditions, Shàngdì, from which it surely originated from, albeit even in this form falling short of the one and only one God of the Abrahamic religious systems.[17] The emphasis of the early Chinese theo-philosophy tradition however, much like the early Hellenic philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle, is upon the importance of behavior, ethics, custom, and ritual as it related to the leading of a happy and balanced life as well as how to create a harmonious and just society.

[1] India being the only comparable civilization from a durability standpoint although its history is not quite as continuous as the Chinese in the sense of regional, linguistic and cultural continuity dating as far back in antiquity.

[2] Oracle bone inscriptions are Chinese character inscriptions on turtle shells or ox bones that were used for divination. It is believed that the inscriptions were made on the shell or bone, the shell or bone was put into a sacrificial fire, and then the priest/shaman or “diviner” would interpret the will of the gods, the will of heaven in this case (Tiān), based upon how the lines and symbols were drawn out of the fire. Despite the very specific religious and spiritual use of these characters, the symbols are abstract enough to indicate that the form of writing that they represent had been around for some time, many centuries if not millennia at least. See http://www.chineseetymology.org.

[3] Classical Chinese was used for almost all forms of formal writing in China up until the early 20th century. See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Classical Chinese’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 27 June 2016, 08:32 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Classical_Chinese&oldid=727190919> [accessed 9 September 2016]

[4] Later generations of Chinese refer to Sīmǎ Qiān as the “Grand Historian” (Chinese: 太史公; Tàishǐ Gōng or tai-shih-kung) given his lasting and unique contributions to the history of Chinese in antiquity.

[5] The “Warring States Period” derives its name from the Record of the Warring States text, or Zhan Guo Ce, a work compiled early in the Han Dynasty which documents the period of ancient Chinese history from the 5th to the 3rd centuries BCE which is marked by political strife and war between competing states and regions.

[6] See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Hundred Schools of Thought’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 31 August 2016, 11:33 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hundred_Schools_of_Thought&oldid=737041169> [accessed 9 September 2016].

[7] From Wikipedia contributors, ‘Tiān’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 29 July 2016, 00:36 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Tiān&oldid=732013599> [accessed 6 September 2016].

[8] See https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/%E5%A4%A9.

[9]See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Tiān’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 29 July 2016, 00:36 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Tiān&oldid=732013599> [accessed 6 September 2016].

[10] See The I Ching or Book of Changes, Wilhelm/Baynes. Princeton University Press 1977. 27th printing (1997). “Shuo Kua / Discussion of the Trigrams” chapter, page 264-265.

[11] Great Commentary B8. Quotation from The Great Commentary (Dazhuan) and Chinese natural cosmogony by Roger T. Ames. Translation by Ames. Published March 2015 in the International Communication of Chinese Culture.

[12] From The I Ching or the Book of Changes by Wilhelm/Baynes. Princeton University Press 1977. “Ta Chuan” / “The Great Treatise” chapter IV pgs. 293-296.

[13] Analects, Chapter “Yáo Yue” verse 3. Translation by James Legge. From http://ctext.org/analects/yáo-yue.

[14] Analects, Chapter “Zi Han” verse 5. Translation by James Legge. From http://ctext.org/analects/zi-han.

[15] Mozi, Chapter “Will of Heaven” 1.2. Translation by W.P. Mei. From http://ctext.org/mozi/will-of-heaven-i.

[16] Mozi, Will of Heaven, Chapter 27, Paragraph 6, ca. 5th Century BCE

[17] A distinction is drawn by some modern scholars between immanent transcendence (Shàngdì/Tiān) and external transcendence (Christian God), allowing for the recognition of the monotheistic strain of thought that is clearly manifest in Chinese antiquity while at the same time drawing a distinction between Western monotheism and its (much earlier and prehistoric) counterpart to the Far East. For more on theology in the Confucian tradition see the chapter Confucian Theology: Three Models in Religion Compass by Yong Huang. Blackwell Publishing 2007 pgs. 455-478 and Chapter 13 from the Dao Companion to the Analects entitled “Religious Thought and Practice in the Analects” by Erin M. Cline. Springer Netherlands 2014.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!