Pythagoras and Plato: From the One to Many

Philosophy to the Greeks not only helped them understand the cosmos, creation and destruction of the universe and the essence of the natural world, but also the harmony within which we as individuals should lead our lives, and in turn – as described by subsequent philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle and others – how the pursuit of excellence and harmonious virtue in our own individual lives corresponded to and aligned with a greater social good within which society as a whole could be organized.

In order to find this source of this “closed” view of the West, this almost obsession to break things apart and drill further and further into the constituent components of a thing until once can literally go no further, one needs to reach back to the beginning of development of thought, and language, in the West. To the ancient Greeks who laid down the intellectual foundations – linguistic, metaphysical and otherwise – that we have inherited in the West through language and culture down through the ages.

Pythagorean Philosophy as Expressed in the Tetractys

One can look at the beginning of this “bound” and “closed” systemic view of the world as having its roots in Pythagorean philosophy, a philosophy that as we understand it rested on the harmony and eternal co-existence of numbers and their relationship to each other, forming the underlying ground of all existence. It is from the Pythagorean tradition as we understand it, that Plato’s fascination with geometry – as reflected most readily in perhaps his most lasting and influential dialogues the Timaeus – was founded.

Pythagoras (c. 570 – c. 495 BCE) , or Pythagoras of Samos as he is sometimes referred to as, was born at the beginning of the 6th century BCE reportedly on the island of Samos in the Aegean Sea. While we don’t have any of his writings directly he was widely regarded as one of the most influential Ionian philosophers in antiquity and his views and beliefs greatly influenced the later philosophical schools of Plato and Aristotle among others. He is believed to have traveled widely throughout the Mediterranean in his youth, studying with the Egyptians, the Chaldeans and Magi, and even the Hebrews according to later biographers and interpreters of his school.

The Pythagorean school was known primarily for their obsession with, their identification with a complex and yet straightforward geometric symbol known as the tetractys – an equilateral triangle. The tetractys represented the core tenet of Pythagorean thought as understood by outsiders and later philosophical schools which either criticized and/or adopted some of its core principles, Plato being the prime example. The symbol, no matter how it is interpreted, represents the harmony of numerical order and relationships, and of course the underlying symmetry and geometry of the equilateral triangle, as reflected in the universe as a whole, the underlying symmetry and harmony of musical theory, and the underlying (or overarching depending upon your perspective) principle that sheds light on the comprehension of the universal order and in turn mankind’s place within it.

The Tetractys symbol is a perfect triangle of sorts that is classically viewed as a base of 4 equidistant points, on top of which a layer of three, then two and then at the top 1 point rested, altogether creating a perfect equilateral triangle with a base of 4 and a total of 10 total points in the system.

While there are a variety of ways to interpret the meaning of this geometric structure and how the Pythagoreans themselves understood it (no works from Pythagoras or his direct followers are extant), most later philosophers imposed a metaphysical transliteration of this geometric structure, applying some Neo-Platonic (actually Middle Platonic which integrated both Pythagorean/Italian philosophical elements with Peripatetic – Aristotelian concepts) principles onto the system, and looked at it as representing the cosmological world order.

At a very basic level of interpretation we have the top point of the triangle as the Monad, or the grand unifying principle from which the entire cosmos emanates, the next layer representing the Dyad or the grand opposing forces of nature within which the natural world comes into being, the third layer represents the great Triad of principles which culminates in later Hellenic philosophical development as the One, the Intellect and the Soul, and then at the base the Tetrad, or foundation of the world as represented by the four basic elements that the ancient Greek believed underpinned the entire physical world – earth, air, water and fire.

This geometric figure, along with the numerical and arithmological attributes associated with it, represented the finest layer of abstraction, the best explanation, of the underlying structure and order of the universe. The cosmos seen as having a beginning from the vast void comes forth, explained in the Judaic mythological tradition as “the spirit moving against the waters”, where the the One begets Two, and the Two beget Three the great Triad, and the Three rests on the foundation of the Tetrad (Four).

We can see this type of worldview all throughout the Mediterranean in antiquity in all the great schools of thought be they primarily philosophical or again theological. The foundational basis of the cosmos and its relationship to number and geometry was no doubt adopted by Plato from the Pythagoreans – “Let no one ignorant of geometry enter here” was said was to be inscribed on the Academy at its entrance. While Plato’s philosophical system was broad and far reaching as reflected in his dialogues, it is in the Timaeus where we find his cosmological world view put forth and geometry, and the tetrahedron specifically, came to represent one of the core foundational building blocks of the known universe.

Philo’s Exegesis of the Fourth Day of Creation in Genesis

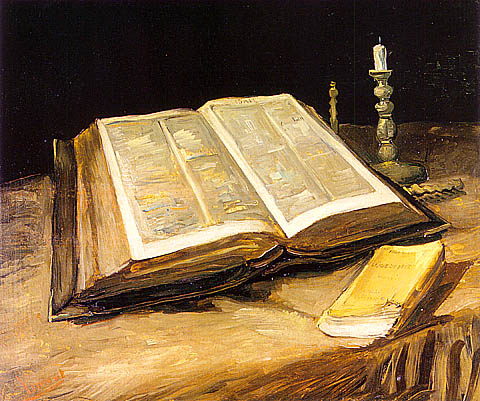

While we again do not have direct sources of the underlying meaning and explanation of this geometric symbol according to the Pythagoreans themselves, we do have later interpretations of the symbol and its underlying meaning from later Hellenic philosophers. One of the best sources of this material is Philo Judaeus (c. 25 BCE – c. 50 CE), or Philo of Alexandria, who lived and wrote in the first century CE in Ptolemaic Egypt. Philo was first and foremost a Jewish scholar, but he was trained in the Hellenic philosophical tradition and read and wrote in ancient Greek, the lingua franca from the Mediterranean in antiquity prior to the prevalence of Latin as advanced by the Roman Empire.

Embedded in Philo’s extensive analysis and “allegorical” interpretations of the five books of Moses from Hebrew Bible, or Pentateuch (πεντάτευχος in Greek or literally “five scrolls”) , specifically in perhaps his most influential work which was a commentary on the beginning of Genesis entitled De Opificio Mundi, or On the Creation of the World, we find a fairly extensive description of the symbolic figure in his explanation of the establishment of the heavenly bodies on the fourth day, the text of which is quoted below :

14 And God said, Let there be lights in the firmament of the heaven to divide the day from the night; and let them be for signs, and for seasons, and for days, and years:

15 And let them be for lights in the firmament of the heaven to give light upon the earth: and it was so.

16 And God made two great lights; the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night: he made the stars also.

17 And God set them in the firmament of the heaven to give light upon the earth,

18 And to rule over the day and over the night, and to divide the light from the darkness: and God saw that it was good.

19 And the evening and the morning were the fourth day.

This passage, which describes the creation of the Sun, Moon and Stars by God (Yahweh) on the fourth day of creation is interpreted by Philo from an intrinsically Hellenic philosophical perspective, and in particular Pythagorean, as he interprets these heavenly bodies and their importance in the theo-philosophical traditions of antiquity as representing the establishment, and ultimate representation, of time and order underlying the universe.

In his explanation of this part of Genesis, in particular on day Four of creation, Philo lays out the understanding of the importance of the number 4 within the context of the Hellenic philosophical tradition, a tradition marked quite clearly – at least from a numerological and arithmetic standpoint – by Pythagorean philosophy as embedded in the tetractys even though he does not specifically allude to the tetractys.

But the heaven was afterwards duly decked in a perfect number, namely four. This number it would be no error to call the base and source of 10, the complete number; for what 10 is actually, this, as is evident, 4 is potentially; that is to say that, if the numbers from 1 to 4 be added together, they will produce 10, and this is the limit set to the otherwise unlimited succession of numbers; round this as a turning-point they wheel and retrace their steps.

Philo describes the underlying perfection, or completeness, implied by the number Four as viewed within the context of the number Ten which he calls the most “complete” or “perfect” number (the sum of the four layers of the tetractys – 1 + 2 + 3 + 4) within classically Aristotelian terms of potentiality (4) and actuality (10). He also describes the sense of motion, or cyclical nature implied by this number 4, which actuates to the number 10, as a “turning point” and “wheel”, alluding to the base 10 that was used by the Greeks for counting and within which after the number 10 one begins to “count again”, starting with 11, 12 and so on.

He also describes the number Four as embedding within it three dimensional space, making it the perfect day (symbolically speaking of course) within which God should establish the foundations of the Heavens within which the world of man was thought to be governed in antiquity, and speaking to the importance the field of geometry held to the ancients, a tradition that became the hallmark of the West.

There is also another property of the number 4 very marvelous to state and to contemplate with the mind. For this number was the first to show the nature of the solid, the numbers before it referring to things without actual substance. For under the head of 1 what is called in geometry a point falls, under that of 2 a line. For if 1 extend itself, 2 is formed, and if a point extend itself, a line is formed: and a line is length without breadth; if breadth be added, there results a surface, which comes under the category of 3: to bring it to a solid surface needs one thing, depth, and the addition of this to 3 produces 4. The result of all this is that this number is a thing of vast importance. It was this number that has led us out of the realm of incorporeal existence patent only to the intellect, and has introduced us to the conception of a body of three dimensions, which by its nature first comes within the range of our senses.

And lastly, in reference to the four elements, and four seasons upon which the ground and order of human existence ultimately rests, Philo concludes with the following summation:

There are several other powers of which 4 has the command, which we shall have to point out in fuller detail in the special treatise devoted to it. Suffice it to add just this, that 4 was made the starting-point of the creation of heaven and the world; for the four elements, out of which this universe was fashioned, issued, as it were from a fountain, from the numeral 4; and, beside this, so also did the four seasons of the year, which are responsible for the coming into being of animals and plants, the year having a fourfold division into winter and spring and summer and autumn.

Porphyry: On the Life of Pythagoras

Another source of Pythagorean philosophy in antiquity is through the works of Porphyry (c. 234 – c. 305) and Iamblichus (c. 245 – c. 325 CE) who were contemporaries in 3rd century CE antiquity and who both wrote biographies of Pythagoras, who by that time had become a pseudo mythical figure. It is from Porphyry that we find the reference that it was Pythagoras who created and “would swear by” the Tetractys, what Porphyry referred to as the “eternal Nature’s fountain spring”.

Within Porphyry’s biography, he describes the fascination of the Pythagoreans with numbers, arithmology, and ultimately geometry thus:

49. As the geometricians cannot express incorporeal forms in words, and have recourse to the descriptions of figures, as that is a triangle, and yet do not mean that the actually seen lines are the triangle, but only what they represent, the knowledge in the mind, so the Pythagoreans used the same objective method in respect to first reasons and forms. As these incorporeal forms and first principles could not be expressed in words, they had recourse to demonstration by numbers. Number one [Monad] denoted to them the reason of Unity, Identity, Equality, the purpose of friendship, sympathy, and conservation of the Universe, which results from persistence in Sameness. For unity in the details harmonizes all the parts of a whole, as by the participation of the First Cause.

50. Number two, or Duad [Dyad], signifies the two-fold reason of diversity and inequality, of everything that is divisible, or mutable, existing at one time in one way, and at another time in another way. After all these methods were not confined to the Pythagoreans, being used by other philosophers to denote unitive powers, which contain all things in the universe, among which are certain reasons of equality, dissimilitude and diversity. These reasons are what they meant by the terms Monad and Duad, or by the words uniform, biform, or diversiform.

Here we see not only an explanation of the underlying geometrical formation of the Tetractys in terms of Platonic Forms, reflecting the underlying sentiment of the period that geometry and numbers are the best and most profound way to describe elemental reality, but also an explanation of the principles of the Monad (the One) and the Dyad (the Two) as the basic archaic elements of the universe from which all numbers, all of reality really, ultimately originates and emanates from.

Porphyry goes on to describe the meaning of the Triad, and in turn the Decad (Ten), which is formed from 1 + 2 + 3 + 4, the four layers of the Tetractys, and underpins the Pythagorean philosophical system which reflected in the Tetractys thus:

51. The same reasons apply to their use of other numbers, which were ranked according to certain powers. Things that had a beginning, middle and end, they denoted by the number Three, saying that anything that has a middle is triform, which was applied to every perfect thing. They said that if anything was perfect it would make use of this principle and be adorned, according to it; and as they had no other name for it, they invented the form Triad; and whenever they tried to bring us to the knowledge of what is perfect they led us to that by the form of this Triad. So also with the other numbers, which were ranked according to the same reasons.

52. All other things were comprehended under a single form and power which they called Decad [10], explaining it by a pun as decad, meaning comprehension. That is why they called Ten a perfect number, the most perfect of all as comprehending all difference of numbers, reasons, species and proportions. For if the nature of the universe be defined according to the reasons and proportions of members, and if that which is produced, increased and perfected, proceed according to the reason of numbers; and since the Decad comprehends every reason of numbers, every proportion, and every species, why should Nature herself not be denoted by the most perfect number, Ten? Such was the use of numbers among the Pythagoreans.

Here we see the direct metaphysical link drawn between Nature and Number, Ten being the reflection of the most perfect of numbers, upon which – to use Philo’s analogy – the (metaphysical) world turns. We also here can see the source of the Trinity, not in terms of the language and words that are used to describe it as defined by the early Church Fathers, but the underlying potency and perfection of the Triad as a symbolic representation of that which is most holy.

Conclusion

So with Philo and Porphyry, both of whom undoubtedly had access to knowledge regarding the Pythagorean philosophical school and their obsession with the tetractys that has subsequently been lost (even though later scholars indicate that his teachings were incorporated into those of the Hellenic philosophical tradition that followed), we find a full and complete explanation of the numerology and arithmology embedded in the Pythagorean philosophical system as manifest in the tetractys, a system which ultimately bounds the spatial dimensions of the material universe within it and from it, as well as enclosing it as it were with a beginning and an end as represented by the underlying numerology, arithmology, and geometry of the figure itself which represented to the ancient philosophers the best possible representation of the inherent cosmological world order.

Peter……

What the fuck are you doing in the business world?? If I’ve ever seen an academic, you sure fit the bill…with Brown under you belt & your writings, I’m positive you’d get your doctorate in a heartbeat & be teaching & be around like minded folks….who you’d greatly appreciate each other, but I’m sure I’m not telling you anything you don’t already know…. I’ve had a drinking cup in the bathroom by my sink for many, many years…on it is written, “Enjoy Life This Is Not A Dress Rehearsal”….they could have added, “And It Goes Really Fucking Fast”

XO, B

>

Man needs to earn his bread and wine… Been working on an interesting piece right now actually, that this is related to. Have you studied the I Ching at all?