A Brief History of the Mystical Arts: Beyond Yoga (Excerpt from Intro of latest work)

The terms mysticism and meditation are used throughout this work, in particular with respect the analysis and study, i.e. the “interpretation”, of the life and teaching of a 19th century Bengali/Indian sage called Paramhamsa Ramakrishna, a topic of much of the last Part of this work.[1] As such, it is required that we do our best to define these terms, even though quite paradoxically the field of study, or domain, within which mysticism as a concept or idea originates, is quite clear that the term defies definition – by definition as it were. Go figure. But we are Westerners here, and we’re certainly not Lǎozǐ or Heraclitus, and particularly given the intended audience of this work being Western academics at least to some degree, we must take the plunge and try to define the undefinable so if nothing else we round out the edges of what mysticism is not, at least from our perspective, and perhaps more importantly, try and place the terms within their proper intellectual, sociological and historical context. In this way the reader can then at least come to a better understanding of how the author views these terms and how they are presented throughout the work, even if again they defy definition in the classical Western intellectual sense.

Mysticism, and the somewhat related practice of meditation, are terms that from a modern, scholarly and academic context are typically associated with longstanding, classically “Eastern”, fields of inquiry. They have nonetheless taken root in the West in the last century or so, mostly within the context of what the West refers to as Yoga, and through this relatively modern cultural transmission many of the terms, words, phrases and ideas associated with mysticism and meditation, have taken root in the languages of the West – English in particular of course. These fields were not always “Eastern” however, and it is worthwhile to trace their roots and origins, back through history and time perhaps get a bit of insight not only into where this break between East and West occurred with respect to the mystical arts and practices themselves, of which meditation is of course one, but also come to a better understanding of the terms within the theological context within which they effectively “emerged”, theology of course being a major theme in this work.[2]

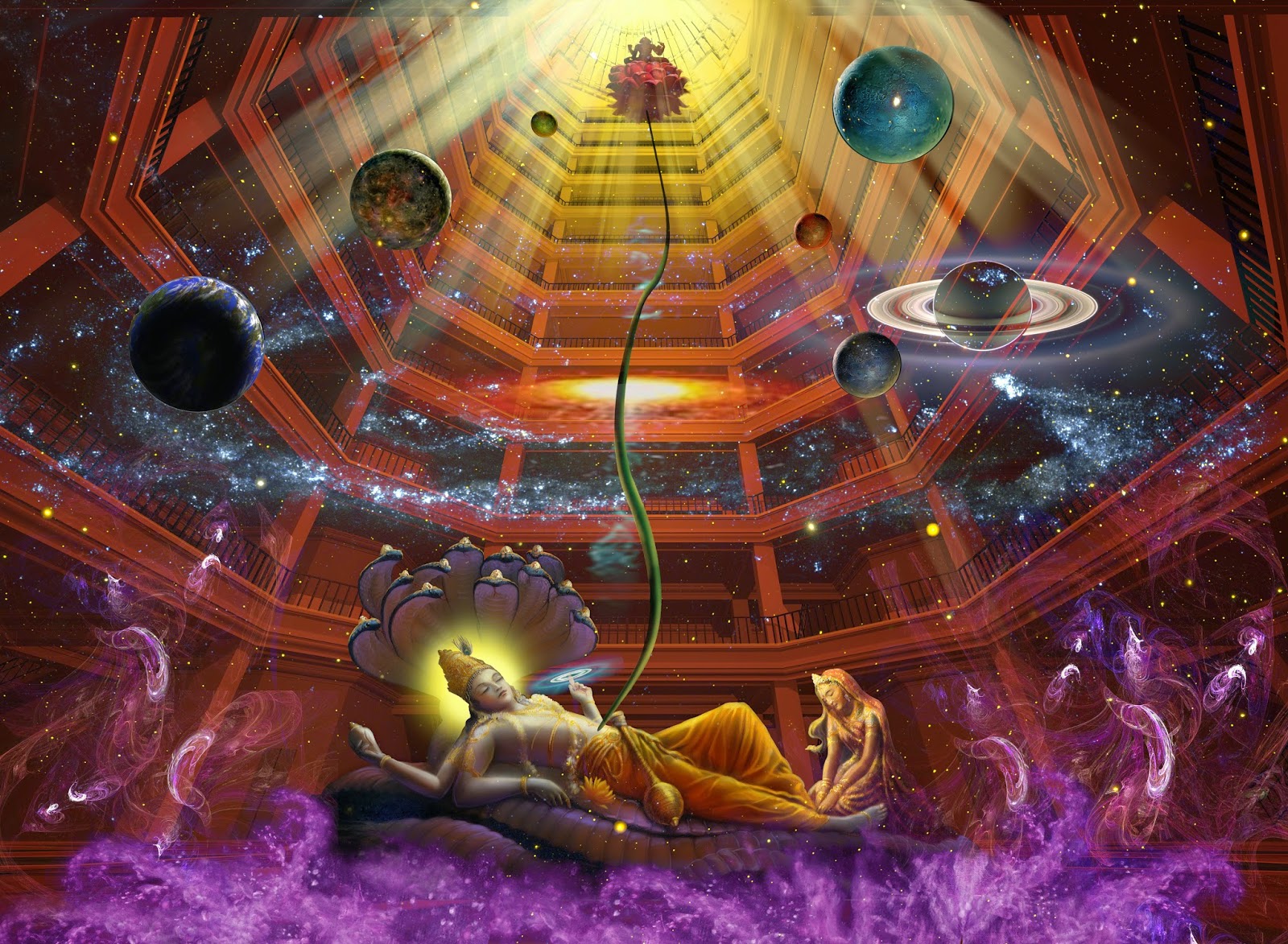

Meditation is a much more technically specific term than mysticism, even though it can mean or imply “concentration”, “deep thought”, or simply “focus”, within the context of the Eastern “mystical” tradition, the term has a fairly well defined history and context, as a translation of the Sanskrit word dhyāna, a word which plays a significant role in the fundamental practices, philosophy and metaphysics of the Indian theo-philosophical tradition as a whole, to which the religions of Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism are fundamentally associated with. In this context, meditation should be understood not in its most broad sense as the word is used in the West, but from a more technical standpoint as defined within the context of the ancient Indian theo-philosophical tradition, Yoga and Buddhism in particular. And to be even more specific definitionally and contextually speaking, while the practice (the art really) of meditation is a fundamental aspect and core tenet of Buddhism[3], and perhaps is most often associated with it, the most precise definition actually comes from the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali, the foundational text of Yoga as we have come to know it in all its forms in the West today.[4]

Within the specifically Indian theo-philosophical tradition of Yoga, understood through the lens of the Yoga Sūtras, dhyāna – the Sanskrit corollary to the modern Western notion of meditation – is one of the “eight limbs”, or practices, that are to be cultivated in order for “Yoga”, samādhi really, to be attained. Yoga in this context, definitionally is a state of mind, a state of being really, where the fluctuations of the mind are halted, or ceased, by means of deep concentration or absorption more or less.[5] Dhyāna, or “deep contemplation” (or again meditation), as the 7th limb of the system of Yoga is the next stage of maturation or development after dhāraṇā, the sixth limb of Patañjali’s system. Dhāraṇā signifies a state of mind that is somewhat less focused, or less intense, than dhyāna but is nonetheless a precursor to it. While dhāraṇā is the holding of one’s mind on a particular object of contemplation, a mantra or focus on one’s breath or the focus on a particular deity for example, dhyāna is a more profound state of contemplation where the particular object of meditation is fixed within the mind as constant stream of thought – where the fluctuations or perturbations of the mind, even with respect to the object of contemplation or meditation itself, is “one pointed” and “uninterrupted”. The difference between dhāraṇā and dhyāna is more one of degree along the progression of Yoga as it is defined within the system itself, the end of which is the eighth limb which is a more commonly used, and nonetheless still not necessarily completely understood Sanskrit term called samādhi, the definition of which of course also hinges upon it’s precursor limbs, or states of mind, of dhāraṇā and dhyāna.

Yoga in the modern era, and in particular in the West, comes in many forms and schools but all of them nonetheless rest upon this eight limbed system of Yoga as it is defined in the Yoga Sūtras themselves, a theo-philosophical system which is classically “Indian”, in the sense that it is the legacy of, and emerges directly out of, the intellectual, theological and metaphysical belief system which is ultimately tied to what we refer to throughout this work as the “Indo-Aryans”, a people and culture who we know of and understand as reflected in the literary tradition to which it is directly tied to, i.e. the Vedas, one of the oldest extant body of literary work of known to man.[6] In the context of this work, we refer to the Indo-Aryans as the people and culture which is reflected in the Vedas, and a people who spoke Vedic Sanskrit, the language of the Vedas.[7] The Indo-Aryans lived and thrived in the Indian subcontinent starting from around the 4th or 3rd millennium BCE or so. The term Indo-Aryan then as we use it throughout, refers to a people and culture, and a related theo-philosophical belief system, that is co-existent with the Vedic corpus itself, i.e. the Vedas – a body of literature that is dated with respect to its so-called “composition” by most scholars (based primarily on linguistic evidence) to between 1500 BCE and 500 BCE depending upon the specific “layer” of material within the corpus itself.[8]

However, while the dating of the so-called “composition” of the Vedas (as well as the “philosophical” portion of the Vedas which is referred to as the Upanishads, the earliest of which are believed to have been added to the Vedic corpus in the middle to late part of the first millennium BCE) is not disputed by the author, we do however argue that the oldest portion of the Vedas (for example the Rigvéda) reflects a set of beliefs, rituals and mythology that reach much further back into ancient history than most scholars consider. The argument for this rests primarily on not only the “form” or “structure” of the Vedas (lyric poetry primarily, what is usually referred to as “hymns”) which points unequivocally to the oral transmission of said hymns for generations, if not centuries, prior to their actual “composition”, but also the typically underemphasized and sometimes even overlooked nature, breadth and power of the oral transmission itself in antiquity – what the author considers to be a “technological innovation” of sorts that is one of, if not the, unique attribute of homo sapiens that distinguishes it from the rest of the species on the planet and in turn is perhaps (as a corollary to the actual invention of language itself) the very reason why mankind has become the most widespread, successful and dominant species on the planet.

For we know in fact that man, in its modern physiological form as homo sapiens, existed for tens of thousands of years in complex hunter-gatherer societies throughout Eurasia (and of course in Africa as well which we know from genetic evidence is where our ancestors in Eurasia came from) prior to the invention of writing and even prior to the advent of “advanced societies”, what is commonly referred to in the academic and historical literature in the West as the so-called “advent of civilization”. Furthermore it is also clear that in order to survive, these ancient humans had to work together and collaborate with each other, i.e. communicate, to not only facilitate the tracking, hunting and killing of large game upon which their survival depended, but also learn to inhabit and survive in a wide range of harsh habitats and environments across Eurasia – for which (archeological) evidence exists that shows that they did quite successfully for some 30,000 years or so give or take before these more “advanced” societies developed, and before agriculture was invented which facilitated the development of more advanced, stable societies which are the hallmark of the so-called “Neolithic Revolution”. It is also clear that in order to facilitate these technological and sociological innovations, “language”, as defined by the ability communicate complex ideas and thoughts between individuals which of course depended upon at least some level the capability for abstract thought, was absolutely essential. And in turn, from the author’s perspective primarily again, along with these advanced intellectual and linguistic capabilities, there also developed and evolved in parallel a means, a method, by which these ideas – these technological and intellectual innovations as it were – could be effectively “transmitted” across generations such that the overall body of knowledge of homo sapiens could increase, exponentially really, to support and facilitate the proliferation of the species itself. In other words, in the author’s view, oral transmission techniques in and of themselves, techniques which we find throughout virtually all of the ancient texts across Eurasia, can be viewed as a specific intellectual (and technological) innovation as it were and as such reflected a form of natural selection from a Darwinian standpoint.

Furthermore, it is not too much of an intellectual leap to consider that this body of knowledge that was transmitted from generation to generation in antiquity, which again also included the method, the means, by which this transmission could take place in as invariant a form as possible, included not only knowledge of technology proper – how to make tools, how to build shelter, how to hunt and track game, etc. – but also cultural phenomena as well, “belief systems”, such that not just species survival could be supported and preserved but that cultural, or tribal knowledge, could also be passed down and preserved as well.[9] This ability to transmit knowledge from generation to generation such that the overall body of knowledge of a people, culture or society would exponentially expand over time, greatly enhancing the probability of survival and persistence of not just homo sapiens itself as a species, but also of the specific permutations of said species, i.e. specific cultures and peoples. This technique of oral transmission then, is arguably a critically important trait, mechanism as it were, to support the flourishing or “thriving” of peoples and cultures in antiquity. In fact, we go one step further and argue that this technique of knowledge transmission, i.e. oral transmission techniques in and of themselves, combined of course with the invention of language itself which predates the techniques of transmission, represents the defining characteristic of homo sapiens, i.e. thinking man, in its later stages of development and is the specific technological, and fundamentally intellectual (sapiens, i.e. “thinking”) innovation which drives the advancement of proliferation of the species which underpin the Neolithic Revolution. These linguistic techniques in toto then, as we see reflected in the earliest literary treatises extant from antiquity across Eurasia more broadly, and in India more specifically in the Vedas, were the specific innovation that underpinned not only the species ability to out-compete, out-survive and eventually effectively take over dominion of the planet, but also underpinned the persistence, the survival, of cultures and nation states which we see take root in Eurasia in the 2nd and 1st millennium BCE as well.[10]

The point we are making here is that in order for this to occur, in order for knowledge transmission to effectively take place, and in order for the scope of knowledge to continue to increase with each successive generation, there must have been technology, a means, by which this transmission could occur and be facilitated. And this very technology is what we find in the very first written records that show up in archeological and literary records once writing is developed and once the necessary tools to support writing on a wide scale are developed as well. In other words, shortly after the invention of language that supported the evolution of ancient hominids into homo sapiens, our ancestors, it is the author’s contention that the means to transmit this knowledge developed as well, the combination of which provided much of the distinguishing characteristics of these ancient peoples, ancient man, that supported their natural selection as it were as the dominant species of hominid on the planet, and throughout Eurasia in particular which is the primary geographic region of focus in antiquity of this work.[11] This particular technological innovation, again one which we see in the earliest literary records across Eurasia as well as in ancient Egypt in fact, is what is referred to in the literature as the oral tradition, or oral transmission techniques – techniques and methods that we find evidence for not just in the first written records that crop up in the 3rd and 2nd millennium BCE across Eurasia, but in fact techniques which appear to be co-existent with ancient (and modern) hunter-gatherer societies themselves which exist without the support of, or need for, writing. We find various oral transmission techniques employed for example by the Native Americans for example, by the native remote tribes that still exist in pockets in South America, by the Aborigines in Australia, even in pockets of remote areas in highly populated and relatively modern countries like India and China for example, in the remote regions of Tibet and Nepal – all of these people and societies have very rich and persistent oral traditions that go back generations, well beyond what many more modern, technologically advanced and writing dependent societies and peoples are capable of imagining, for the very reason that modern humans, those that have grown up with the support of writing and books, no longer have the need for, nor the capability, to memorize or remember bodies of knowledge like people in antiquity did prior to the invention, or widespread use, of writing.

It is not too far-fetched to imagine, and in fact we have modern day examples of this very fact, that the oral transmission of ideas, can persist in an essentially consistent form, for hundreds if not thousands of years. Mankind’s survival in antiquity arguably depended upon this very capability, and therefore, necessity being the mother of invention as it were, there developed very specific techniques, intellectual “technologies”, to support this capability. It is these techniques in fact that we find in virtually all pre-historical peoples and societies, Eurasia being no exception, in order to support the transmission of the very particular and unique sociological, historical and theo-philosophical traditions of the respective peoples and cultures in question. Techniques, intellectual “technologies”, that again were “invented” or “devised” for the relatively invariant transmission of ideas across generations – the invariant transmission of sounds, ceremonies and forms of worship in fact, i.e. what we refer to herein as theo-philosophical knowledge. The specific tools that were used were lyrical, in the sense that specific verse and rhyming techniques, effectively mnemonic devices, were employed to facilitate memorization and transmission, along with of course the use of mythical narratives as well, i.e. mythology – all of which made things easier to remember, understand and pass down from generation to generation.

And this is precisely what we find all throughout the very first texts that show up in the archeological record after the invention of writing, where scholars, priests or poets, or scribes – a sociological designation which is an outgrowth of what are referred to sometimes as shamans – transcribed or wrote down, i.e. “compiled”, as the documentation of the very ancient lore that had supported that specific people or society for generations over a time period of centuries and millennia even. This is what we find inherent in the “form” of the Far Eastern texts of the Dao De Jing, and the Yijing (although the Yijing is not lyrical per se but more mathematically and logically structured), as well as the ancient Chinese poems such as the Heavenly Questions, in the major epics of the Hellenes such as the Iliad and the Odyssey and the Theogony of Hesiod which were transcribed in hexameter, or lyric, verse, in the great Sumer-Babylonian epic the Enûma Eliš, in the Pyramid Texts and the so-called Book of the Dead of the ancient Egyptians, as well as in the earliest written records of the Indo-Aryans and the Indo-Iranians as well, that is in the Vedas and the Avesta respectively.

Scholars of ancient Studies typically consider that the “content” of these ancient texts could only be a few hundred, or at most a thousand years older than the date when they were “transcribed”, or “written down”, but it is the author’s contention that is altogether possible, and in fact probable, that the content of these ancient texts, and probably much of the underlying rhythmic and linguistic structure along with the mythical narratives themselves, persisted for thousands of years prior to them being written down. And in turn that the technology and capabilities which underpinned the oral transmission tradition which had supported mankind’s development during the Upper Paleolithic and into the Neolithic Era (a period of some 20 to 30 thousand years) dissolved for the most part once it no longer became necessary. In other words, once these ancient theo-philosophical traditions were written down, compiled as it were, the specific technological innovation which had supported the transmission of these idea, the intellectual capabilities that underpinned oral transmission as a “tool” or “technology”, disappeared along with it.

As such, it is the author’s contention (which although is shared to a certain extent by some ancient historians and scholars, none of them seem to allow for the oral transmission techniques to reach as far back in history as the author theorizes and concludes based upon the analysis and research in Parts I and II of this work) that the dates of the “content” of some of the oldest extant literature we find throughout Eurasia, the Vedas being the prime example, should be moved even further back in history than what most ancient historians and scholars attribute them to – a method of dating that relies on a much more “literal” and “factually scientific” dating technique that dates the specific texts relative to their associated archeological or linguistic context rather than their theo-philosophical “content”. This perspective on the dating of the “content” of this material which shows up in the archeological record once writing is invented, provides for an altogether different perspective entirely not just on the possible “dating” of the material itself, but (as we argue throughout this work and especially in Parts I and II) also supports the hypothesis of the potential shared origins of much of the theo-philosophical “content” that we find in antiquity – in Eurasian antiquity specifically which is the geographic nexus of this work. In this context, we can refer to and discuss a “Eurasian” theo-philosophical tradition that is “reflected” in the earliest extant texts that we have from all of these ancient peoples and civilizations within which we find many common themes, motifs and narratives.

The argument then, is that the “content” of the earliest extant literature from antiquity throughout Eurasia, Vedas included, are much earlier – millennia perhaps – than most, if not all, ancient historians typically date the source material to. Once this is established, or at least granted as a potentially conceivable hypothesis, one can then begin to discuss the possibility[12] of a shared common (intellectual) ancestry of this material, i.e. the ideological content as it were, of the earliest extant literature we find from ancient history throughout Eurasia. This thesis again is based primarily on the known and well documented ability of people to transmit language in lyric poetry, form for hundreds if not thousands of years with very little variance, as well as the commonalities linguistically and theo-philosophically that we find in the earliest extant literature from all of these ancient peoples of Eurasia which are studied within the context of this work – specifically the Hellenes (the Greeks), the Indo-Aryans, the Indo-Iranians, the Sumer-Babylonians, and the ancient Chinese which are all explored at length in Parts I and II of this work.

Regardless of the strength of the arguments made here, in a time period that lacks much if any intellectual records in fact, what is certain however, is that the transmission of knowledge in antiquity, prior to the development of writing, was done in oral form and was facilitated by the use of lyric and or hymnic poetry. A specific linguistic technique which shows up in literary form in virtually all of the earliest extant literary treatises from the various cultures and peoples throughout Eurasia in antiquity (2nd and 1st millennium BCE primarily), a linguistic technique that facilitated, and was specifically designed for, consistent and persistent, i.e. invariant, oral transmission of ideas. We argue then that a case can be made, albeit circumstantial, that these techniques which facilitated and supported the transmission of ideas, in mythological and theological form mostly, for millennium prior to the invention and proliferation of writing, is in all likelihood the very reason, the necessary condition as it were, that mankind developed the capability of “advanced civilization” itself.

This period in ancient history has come to be known as the Neolithic Revolution and is characterized by the widespread use and adoption of agriculture and the domestication of animals, which in turn led to the establishment of trade and commerce, which in turn led to the invention of writing itself along with the tools and techniques that were necessary to support writing. All of which in the aggregate come to characterize what we effectively call “civilization” from an ancient historical perspective, even though it is altogether very likely, and in fact very probable, that long before the invention of writing – and long before the invention of agriculture of the domestication of animals – human beings, i.e. homo sapiens, were communicating and passing down complex ideas via the use of these linguistic techniques, intellectual technologies in a sense, in order to support, and in turn ensure, the survival of their “people” – from a socio-political perspective, as well as from (the very much related) theo-philosophical perspective as well. The latter being a main topic of Parts I and II of this work.

Mysticism then, within the context this work, is distinct from the modern, 20th century usage of the term which was created primarily to distinguish “Eastern” spiritual practices (that underpin again Yoga and Buddhism primarily, and ancient shamanic practices more generally[13]) from the study of Western theology, e.g. Comparative Religious studies, which is much more dogmatic and “scripturally” based. We use the term as a distinguishing characteristic of ancient theo-philosophy in general, a tradition that is reflected and preserved by means of language and forms of writing yes, but also by oral transmission techniques, as well again lyric poetry, primarily. It is these common themes and characteristics of virtually all of the ancient the-philosophical texts from antiquity that we find in the very earliest literary texts throughout all of Eurasia and the Mediterranean which all to some extent contain “mystical” undertones and themes – mystical in this sense denoting an experiential oneness and connection with the ground of being and universal existence itself, and one which only later, as ancient civilizations evolve and progress, becomes transplanted with – albeit in allegorical and mythological form – deities and their respective worship via means of specific rituals and incantations, i.e. hymns.

This later theo-philosophical development in antiquity, which is born out of its mystical roots as it were, is characterized initially by ancestor worship, and then in turn by ceremonial worship, which in turn evolves into cultural specific mythology and the worship of “divine” figures who are depicted as heroes and associated with various aspects of the natural world – like the mother goddess who is worshipped to support fertility for example. So even though mysticism then as a modern designation of these very ancient “belief systems”, along with their underlying practices, or arts, as exemplified by the Indo-Aryan art of meditation as it were, is a necessary designation to distinguish these types of belief systems and practices from Western theology, i.e. Religion in the most orthodox sense, within the context of the modern Western intellectual and academic, or scholarly, landscape, from the point of view of the ancient peoples themselves from whom these practices and techniques that we call mystical originate from, had no such designation as the worldview of these ancient peoples was fundamental mystical at the core. That is to say fully unified and experiential, passing even beyond the boundaries of death, and integral to life, and reality, itself – a fundamental and all-pervading characteristic of human experience, of existence in all its forms, and as such did not need definition per se.

Mysticism, from this specifically ancient theo-philosophical perspective, is virtually ubiquitous in the mode of worship and underlying belief system of all the cultures and peoples through Eurasia in antiquity which we see reflected and crystalized particularly in the earliest theo-philosophical treatises of the various peoples and cultures which inhabited this geographic region during this time period in ancient history (Eurasia during the 3rd, 2nd and 1st millennium BCE). If we then take the next logical step to search for the roots of this mysticism, we find that it can be traced – ideologically and linguistically – not just across the Indo-European linguistic and cultural landscape (the Proto-Indo-Europeans), but also even to Afro-Asiatic speaking peoples as well (in Northern Africa), begging the question of how far back in time these theo-philosophical tenets and principles upon which our definition of mysticism is based, could have potentially originated. This logical progression of the tracing of these ideas as far back as the 4th and even 5th millennium BCE, provides much of the basis for the argument of the shared origins of what we refer to throughout this work as “theo-philosophy”, common themes and literary techniques that are to be found throughout Eurasia in antiquity – despite the linguistic peculiarities and specificities of individual cultures, peoples and of course the ancient theo-philosophical works themselves (which surround the very first literary compositions which show up in the archeological record once writing is invented and is spread throughout its respective societies in its respective form – be it hieroglyphic, cuneiform, ancient Chinese, Sanskrit or Greek depending upon the culture and geographic region and people in question), which make them “appear” different from a theo-philosophical standpoint but at closer look can be seen as reflecting very similar ideas and concepts – theo-philosophically speaking at least.

It is upon this basis that we speak of and use the term mysticism to reflect the very ancient and longstanding theo-philosophical belief systems which underpin all of these ancient theo-philosophical works from antiquity across all of the cultures and peoples throughout Eurasia and Northern Africa really, and in turn the surrounding mythology (mythos) that is characteristic of ancient man in general. The cultural specific mythos traditions having evolved of course from their theo-philosophical precedents, ideologically at least, which presumes that the “spirit world” (which consists of the realm of the dead along with the realm of the “gods” as well) was not just “real” but that this aspect of reality actually governed, or presided over, the physical and natural world that ancient man depended upon for survival. It is this belief system of the role of the spirit world over the physical or natural world, that in fact underpins all of the ancient forms of ceremonial worship, and in turn provides the theological, and socio-political really, basis for virtually all of the nation-states that emerge in the ancient world as “civilization” takes root, and as more complex and advanced societies, which are the hallmark of the Neolithic Revolution in fact, emerge – where virtually all of the kings, emperors and pharaohs of these ancient nation-states all claimed descent from, or alignment with, these ancient gods or heroes in one respect or another.

[1] Ramakrishna is the main figure, as it relates to the notion of mysticism and ontology in particular, in the last three Chapters of Part IV of this work.

[2] Even though an historical and cultural context is provided, the author will also posit the notion that mysticism at some level is co-emergent with the (modern) human condition, i.e. a prerequisite and necessary condition for modern man, or homo sapiens.

[3] Think Buddha sitting in contemplation under the Bodhi tree where he “achieves” or experiences nirvana, what we in the West like to call “enlightenment”.

[4] The Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali is a 3rd/4th century CE text made up of almost 200 aphorisms or verses which is attributed to the ancient Indian sage Patañjali. This work, and its place intellectually within the context of ancient Indian theo-philosophy (orthodox Indian theo-philosophy primarily), is covered in Part IV of this work in the Chapter on Vedānta and Yoga, and Vivekananda, the spiritual successor of Ramakrishna.

[5] Yoga Sūtras, 1.2. yogaś citta-vṛtti-nirodhaḥ in Sanskrit where citta is a technical term that means “mind stuff”, vṛtti means “various forms” or “fluctuations” more or less, and nirodhaḥ means “inhibit” or “cessation”. Hence the English translation as something along the lines of “Yoga is the cessation of the fluctuations of the mind”.

[6] The oldest strata of hymns in the Vedas can be reasonably dated as far back as the 2nd millennium BCE, if not prior.

[7] Vedic Sanskrit is an Indo-European language, the root of the language tree of virtually all Western languages. Throughout this work we use the philological, or linguistic, term “Indo-European” to not only designate a set of people that spoke languages that share a (theoretical) common ancestor, but also who the author argues also share a common cultural and theo-philosophical ancestry as well. Linguistically this common shared, theoretical, ancestral language shared by all “Indo-European” language speaking people in antiquity is referred to philologically (the study of linguistics or language) as “Proto-Indo-European”.

[8] This time period in Indian history sometimes referred to as the “Vedic period” or “Vedic Age”.

[9] Ancestor worship for example, which we find evidence of across virtually all of ancient human populations in pre-historical times, reflects this very principle in fact.

[10]We know that at the same time that homo sapiens was spreading across Europe, the Mediterranean and Asia – collectively what we refer to as Eurasia throughout this work – that at the same time there existed other species of hominids in the same territory at the very same that homo sapiens competed with, and also in fact interbred with – Neanderthals for example.

[11] The argument we are making here is that the requirement for the effective transmission of knowledge, was in fact necessary for the survival of ancient man and underpinned his ability to dominate (and most likely exterminate) all other forms of ancient hominids. And all of this must have occurred well before the invention of writing which we don’t find in the (Eurasian) historical record come into widespread use until the 3rd and 2ndmillennia BCE.

[12] As originally conceived of by the Harvard Sanskrit scholar Michael Witzel in his work Origins of the World’s Mythologies.

[13] As put forth by Mircea Eliade in his body of work for example.

PETER, is this you? Want to forward it to my friend who’s into philosophy..

>

Yes it’s me. Pls do. Thx Bob.