Ancient Egyptian Mythos: The Weighing of the Heart, Ra and Ma’at

Perhaps the earliest mythological tradition we find documented, or evidence of, is that of the ancient Egyptians, a culture and civilization that evolved out of the settlement of the Nile delta river region in Northern Africa around the turn of the fifth millennium BCE. The Dynastic period of Egypt begins according to conventional Egyptian chronology with the unification of Lower and Upper Egypt circa 3150 BCE under the first “pharaoh” called Narmer, more commonly referred to as Menes. Archeological evidence for human settlements in the Nile River delta goes back to the end of the Upper Neolithic period, a period of human evolution going back to the 11th and 12th millennium BCE before the advent of agriculture and the advanced domestication of animals. We have evidence for more advanced settlements coalescing in this region in and around the 6th millennium BCE however, evidence that points to a society that had mastered various arts of animal husbandry and domestication, had developed techniques for the creation of pottery and ceramics, and had also invented and were using advanced stone tools and copper that allowed for them to begin to manipulate and leverage the rich and fertile Nile River delta to build more developed and advanced society.

These people from Pre-Dynastic Egypt clearly had at least the beginnings of a fairly evolved religious and/or mythological tradition, a tradition that allowed for the unification and consolidation of various nomadic tribes from the region and provide for socio-political stability that supported the unification of the Upper and Lower Egyptian valley, what we have come to know and call in Egyptology circles as “Dynastic” Egypt from antiquity.[1] Ancient Egypt was a land conquered by many ancient civilizations over the centuries, and yet one with a deep and rich history itself, one steeped in the rule of the Pharaohs in the land of the North African Nile River Delta valley, an area inhabited by mankind since as least as far back as 30,000 to 40,000 years ago, and one which developed a rich and unique mythos and social structure which rested on the firm belief that their leader, their King or Pharaoh, was the human manifestation of the divine on earth, directly connecting the established authority and governance of the people with their worship and belief in god, which for most of Ancient Egyptian history was associated with Atum, or Atum-Ra.

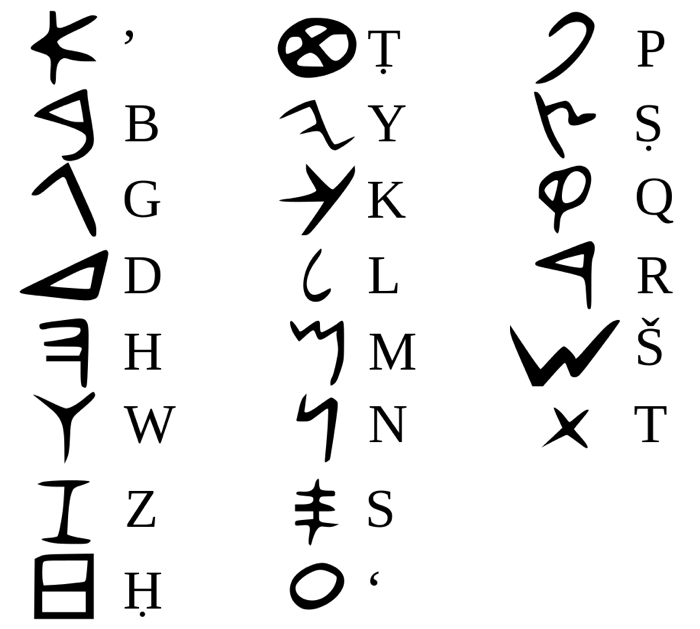

Before ancient Egypt was conquered and ruled by foreigners starting with the Persians in the middle of the first millennium BCE, then followed by the Greeks under Alexander the Great in 332 BCE, then the Romans in 30 BCE for some 5 or 6 centuries and then the Muslims/Arabs for some thousand years plus thereafter, it was one of the most sophisticated and advanced of all the ancient civilizations in the Mediterranean and Near East, with a system of writing and architecture that dates back to the 4th millennia BCE, making it one of, if not the, oldest civilization of mankind. The beginning of Ancient Egyptian civilization is typically marked by the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt by its first pharaoh[2] in the latter part of the 4th millennia BCE, what modern historians have come to call the Predynastic Era which succeeded the end of the Upper Neolithic in the Egyptian delta. This period of unification of Upper and Lower Egypt is also the time period associated with the emergence of Egyptian forms of writing as well, at first with hieroglyphs which we find inscribed on the tombs of pharaohs from this period, and later in the tombs of the upper and middle class as hieroglyphic inscriptions became more common and the hieroglyphics evolved to include not only ideograms and logographic (picture) elements, but also alphabetic elements to capture specific pronunciations and annunciations of spells designed to capture the specific annunciations and words used by the Egyptian priesthood for specific ceremonies and rituals, most notably of course the burial of the dead.

Alongside the development of hieroglyphs which evolved for some two millennia (and was still used up until the 3rd and 4th centuries CE after Egypt came under first Greek then Roman rule), a sister script called hieratic[3] also emerged which although closely related to hieroglyphics was character and phonetic/alphabet based. Hieratic was easier to write than hieroglyphs and like its sister hieroglyphs, was initially only used by priests and scribes to transliterate specific rituals and spells. Eventually, in the middle and latter part of the first millennium BCE, hieratic evolved into demotic, a script designed for more secular use that in most instance was used to capture the language of the period of the same name, i.e. Demotic, which succeeded Middle and Late Egyptian which had been the language spoken by Egyptians for the preceding few millennia in some form or another.

The Egyptian Demotic language (not to be confused with the modern Greek language with the same name, i.e. “demotic” which is typically written with a lower case “d”) and the script that supported it that is referred to with the same name, i.e. demotic, was prevalent in the middle and late first millennium BCE and was used for almost a thousand years up until the 5th century CE or so. Both hieroglyphics and hieratic script are used throughout ancient Egypt from the Predynastic Period (c 3100 BCE) all the way through the 6th century CE or so and it is through these writing systems, and the languages transcribed therein, that we can get a glimpse of the theology and religion of ancient Egypt.[4]

Our current historical view of categorizing ancient Egyptian history into Dynasties, typically marked by roman numerals, is derived from the first Egyptian historian Manetho, a 3rd century BCE priest and historian from Egypt who authored a three-volume treatise of the history of Egypt entitled Aegyptiaca, or “History of Egypt”, a period of Egyptian history when it was under Greek, or Hellenic influence hence the use of Greek to author his work. Manetho, according to later historians and excerpts of his work that do survive, gave a detailed and Egyptian perspective on the history of Egypt, beginning with the period of Egyptian societal consolidation under the rule of a single unified King or Pharaoh which he calls Menes circa 3100 BCE. His work is presumed to have been motivated by providing an Egyptian perspective on the history of Egypt in contrast to the one provided by Herodotus several centuries prior, whose perspective was not only foreign but also lacking with respect to a proper chronology and depth of coverage.

Later, more modern Egyptian historians (aka Egyptologists) break down the periods of ancient Egyptian civilization into different successive periods, each earmarked by the transition from one dynasty to another, where a dynasty doesn’t necessarily represent a blood lineage from one ruler to the next but some cultural or societal break in Egyptian history that denotes the transition into different period. All ancient Egyptian texts and inscriptions fall into one or more different periods, and Egyptologists typically use the Dynastic classification to denote the period within which a particular text, form of writing, or inscription is found so in order to have proper context of the time period and socio-political context of a given theological text or inscription, it was important to be able to classify it in the appropriate Dynasty and/or period.

The Dynastic period of Egypt lasting some three thousand years or so reaching far back in antiquity is characterized not only by a rich and unique pantheon of gods and their associated mythology (and ritual) that not only emphasized the belief in their ruler as a manifestation of god on earth whose authority derived from divine provenance, but also by a marked with what can only be call an obsession with the transmigration of the soul and the belief in an afterlife, emphasis that perhaps derives from the context within which almost all of this material and inscriptions survive down to us, namely first through Pyramid and Coffin (sarcophagus) inscriptions in the 3rd and 2nd millennium BCE, and then later on papyrus documents as the literature become more widespread and prevalent in society, and more standardized as what is known today as the Egyptian Book of the Dead.

This extant material, inscriptions in hieroglyphics within pyramids, tombs and on sarcophagus and then later in hieratic and hieroglyphic script on papyrus, indirectly refers to and incorporates their cultural and spiritual belief system and worldview, corresponding to what today we would call religion. All of this material was in fact crafted and designed specifically to protect, guide, and preserve the bodies and souls of the Egyptians into their journey into the afterlife, perhaps better translated as the “netherworld”, giving rise to their practices of mummification and pyramid and tomb building which were attempts to preserve the body, and its soul, for its journey beyond life into the afterworld.

The incantations, spells and utterances inscribed in these burial sites which constitute the core part of our knowledge of the mythos of ancient Egypt was apparently initially reserved only for the Kings and Pharaohs in the early dynastic period and Old Kingdom. These writings have come to be known as the Pyramid Texts. This tradition then spread to the aristocracy during the First Intermediate Period and Middle Kingdom where we find inscriptions on various sarcophagi and tombs, texts and literature that are known to modern historians as the Coffin Texts. This in turn evolved to its most mature and standardized form in Egyptian antiquity which was adopted more broadly by the general population in the New Kingdom dynasties through the Ptolemaic Period and is known to us as the famed Egyptian Book of Dead, a compilation of myths, stories and fables from Egyptian lore are found on papyrus scrolls associated with burial grounds of many tombs from this era[5].

Egyptian mythos is undoubtedly best known for this association, perhaps more aptly described as an obsession, upon the burial and rituals associated with death and the extensive steps taken to prepare the Soul (most commonly associated with the Egyptian term “Bâ”) for its journey into the afterlife, and it is from this context surrounding death and the afterlife for the most part from which we gain insight into Ancient Egyptian religious beliefs. Therefore, ancient Egyptian religion is closely associated with these sophisticated and wide-ranging spells and incantations and their associated mythology surrounding death and the journey of the Soul in the afterlife.

The Egyptian notion of Bâ was somewhat different than our conception of the Soul, perceived to be the aspect of the individual in toto which was permanent and persisted beyond death, perhaps best described as the fundamental essence of the individual which was deathless and timeless. Bâ was also used in reference to inanimate objects as well, denoting the broader meaning of the word in Egyptian to describe the essential nature of a thing, either animate or inanimate, with perhaps a close correspondence to Plato’s notion of form and/or Aristotle’s being qua being, or that which characterizes the primary essence of a thing and defines its existence, which he outlines in his Metaphysics.

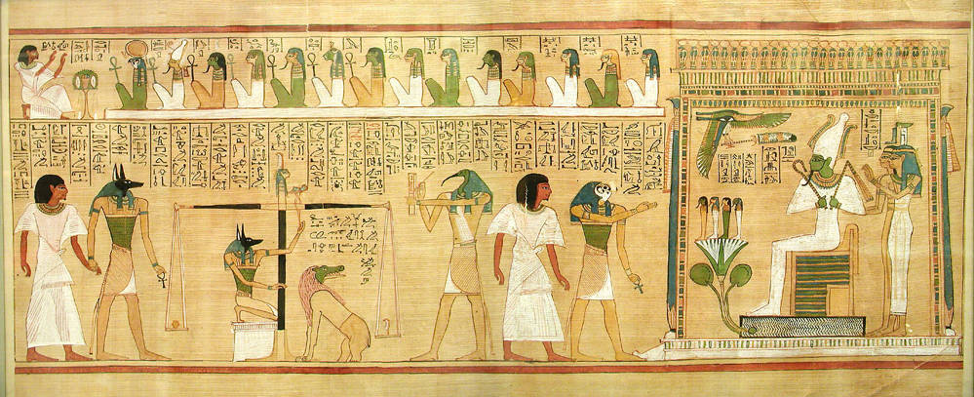

Furthermore, as reflected in the Book of the Dead which represents the most mature form of the Egyptian religion/theology as it stands from the latest part of Egyptian antiquity, special importance was given to not only the individual’s name which was given to them at birth, rén or rn, which the Egyptians held supported the continued existence of the soul as long as it was kept alive and spoken, but also special significance was given to the heart, ib or jb, which was looked upon as the seat of all human emotion, feeling, thought, will and intention. The importance and relevance of the heart in Egyptian theology can be seen from the classic Weighing of the heart ceremony which is depicted taking place in the underworld upon someone’s death where the individual’s heart was weighed/balanced against the feather of Ma’at representing truth, justice, or order; the outcome of such balance determining the ultimate fate of the individual. This practice and imagery as depicted in the Coffin Texts and then later encapsulated in the Book of the Dead most certainly has parallels to the Christian moral framework based upon the notion of Last Judgment.

Depiction of Ancient Egyptian Weighing of the Heart ceremony from the Book of the Dead. [6]

Ancient Egyptian theological and mythological beliefs from antiquity, as reflected first in the Pyramid Texts from the Old Kingdom, the Coffin Texts from the Middle Kingdom, and then further structured and canonized in the Book of the Dead in its various forms, displays a fairly advanced and complex system of beliefs characterized by the worship of many different deities in a variety of forms, each reflecting some aspect of nature and/or some anthropomorphized (or pseudo-anthropomorphized as the case may be) aspect of God, consistent in fact with almost all of the middle and late Bronze Age contemporaneous cultures and civilizations in the Mediterranean region and even into the Near and Far East.

A byproduct of the deep antiquity which was represented by these various (primary) sources of material, is the variety and breadth of the Egyptian mythos in general. There isn’t just one creation narrative that we can find, there are in fact several versions that survive. And while each of the versions is basically stacked with the same cast of characters, each tells the story with its own nuances and with the prevalence and predominance of one or more Egyptian deities over another, reflecting the religious emphasis on the worship of particular deities in the “Egyptian pantheon” (if we may call it that) that were representative of a particular metropolitan center or geographic region within Upper or Lower Egypt and/or the particular background and genealogy ascribed to a particular king during a particular era. These mythological narratives then became associated with particular city and region, and a particular time period, each again associated with its own “host” or “native” deity as it were, from which vantage point their mythology, and again more specifically their creation narratives, were told.

Generally, when studying the theo-philosophical traditions of ancient civilizations and cultures before the advent and proliferation of writing, one must rely less on actual firsthand accounts – like the Greek historian from the 5th century BCE Herodotus or the Egyptian historian Manetho (3rd century BCE) for example – and more on archeological evidence and general knowledge of the way of life of these ancient peoples. A way of life that is characterized by the transition of nomadic tribes, who spoke various languages and had their own distinctive customs and belief systems, to a more domesticated and stationary existence. An existence that typically sprang up around a fertile river delta region that facilitated farming and agricultural developments and went hand in hand with various technological developments like architecture, irrigation and warfare. For once one settles in a particular region one must at the very least have the capability to defend it and at the very most have the ability to expand it as most ancient rulers had the desire to do. All of these developments required a more consistent cultural and linguistic narrative in order to facilitate this advancement of civilization, one that for the most part was in the best interests of the people themselves, i.e. represented a more stable and persistent life style and community.

What complicates matters for the study of ancient Egyptian history however, more so than for the study of ancient Greek or Roman history for example, stemming in no small measure due to its deep antiquity, is that first hand sources and accounts were limited at best, and mostly come from burial grounds or inscriptions of kings and aristocrats which represent a somewhat skewed and distorted version of history, a version that they wanted told and remembered and does not for the most part have the reliability and accuracy of later historical records, i.e. they blended mythology and hearsay alongside historical fact and it is more often than not difficult to tell the difference.

For what characterizes the earliest of civilizations is the eventual congregation and assimilation of various groups and tribes of people into larger communities that share a common language, i.e. form of communication, common belief system, and a cohesive and codependent livelihood. A livelihood where each member of the community serves a given purpose to serve the larger good so to speak and supports the overall growth and protection of the community at large. This presumes, and evolves in parallel to, what historians call “specialization”, where members of the community have specific skills that can be leveraged by the broader community and through systems of barter or trade, each of the members of the larger community can depend upon each other to support the growth of the community at large. As these early civilizations evolve to support larger numbers of people across more geographically expansive regions, systems of recording transactions, tracking history and lineage, the establishment of governance and authority and the classification of society necessary evolves out of necessity. Hence civilizations and what we call in the West “progress”, must in fact evolve to support larger and more complex socio-political environments.

Belief systems, which are encoded in language and ritual, evolve along with these other characteristics and typically in antiquity this meant that older forms of “worship”, were kept under close supervision and secrecy by a priestly (and later literary and scholarly) class of citizens who were closely affiliated with, and were sponsored and supported by, the ruling class. The priestly class general speaking then in antiquity, and specifically characteristic of Dynastic Egypt, were directly associated with the king. For the Egyptian king, that later came to be known by outsiders as the “pharaoh”, was thought to be descended from the ancient gods themselves and it was from this authority that he ruled the people. Because of this dependency, the prevailing mythology, and the capital city as well, tended to move and evolve with the leader depending upon which god he (or she) was primarily affiliated with.

This is in contrast to the Greek or Roman civilizations for example, where the culture, and in turn the mythology and theology, was much more distinct and separate from the ruling class, even if ultimate authority was still kept with the Roman Emperor for example, of the Greek Assembly – each of which throughout its history used this power to influence theo-philosophical thought. For if nothing else we inherit at least this basic concept of separation of “church and state” if you will, from these classically Western civilizations, the same civilizations to which we attribute the invention and establishment of the first forms of democracy. As the Greek form of government at least was not authoritarian per se, at least not based upon divine authority or upon royal descent from the gods, an attribute that was later acquired by the Roman Emperors even though it did not carry the same sort of direct theological descent attribute that was so characteristic of the earlier civilizations of the Mediterranean and Near East.

It is this socio-political feature of their society in particular that lends itself to a more consistent and coherent mythological (and in turn theo-philosophical) tradition, as the theologians, or priests as it were, could more or less perform their duties somewhat separate from and removed from those that legislated and ruled. This classically Western socio-political structure in turn what allows for an environment within which the likes of Homer, Hesiod and Herodotus, and then in turn the later Hellenic philosophical tradition as a whole most notably represented by Plato and Aristotle, can flourish.

In studying and analyzing the ancient Egyptian mythos from antiquity as evidenced by the archeological evidence as well as the written records, and in particular in looking at their various creation stories or myths, i.e. their metaphorical and allegorical descriptions of the creation of the universe, one of the distinguishing characteristics that stands out and is reflective of the ancient Egyptians that distinguishes it from the neighboring civilizations around the Mediterranean is that a consistent narrative of their mythology is entirely absent. We have no counterpart to Hesiod’s Theogony or Ovid’s Metamorphoses from ancient Egypt, no doubt stemming from the deep antiquity within which the civilization of study represents as well as the plethora of native tribes and various groups of people which were representative of this time in prehistory in the Nile River delta region (and one of the primary reasons why the people were so hard to consolidate under one rulership no doubt, a hallmark of Dynastic Egypt).

This is both a blessing and a curse as while we get have glimpses of a wide variety of ancient myths and gods that were prevalent during the Early dynastic period, no doubt reflecting stories from Pre-Dynastic Egypt, which give us a fairly broad perspective on the mythos of this ancient civilization, we do not have a consolidated, canonical version of their mythology that can be directly contrasted with their neighboring civilizations – like the Hebrews, the Greeks, or the Persians (and to a lesser extent the Sumer-Babylonians/Assyrians), all of which – given at a much later time in history – compiled more structured and formalized versions of their theological traditions.

To find out about Egyptian mythos then, with a particular emphasis on creation narratives which at their core form the basis of their theo-philosophical belief systems, one must parse through the ancient Egyptian texts and inscriptions themselves. A written narrative that consists mainly of hieroglyphic writings, the earliest form of Egyptian writing, found written on the walls of various burial sites and tombs (and later on papyrus in the latter part of the 2nd and first millennium BCE), that describe various hymns, magical and funeral and rituals that were meant to serve as guideposts and protection for the passage of the living into the realm of the dead. We then can combine these direct source materials with (much later) writings and references to Egyptian religion, culture and civilization from the Greek historians and philosophers form the latter half of the first millennium BCE – most notably the likes of Herodotus (c. 484 – c. 425 BCE), Plutarch (c. 46 – 120 CE), Diogenes Laertius (c 3rd century CE), all of whom speak to a long standing and deep cultural exchange between the peoples of the Nile River delta and their neighbors in the Mediterranean.

The Egyptian civilization formed primarily around the shared experience of the Nile River, with its annual cycles of flooding and recension upon which the entire society depended upon for nourishment and survival. Ancient Egypt was divided between Lower (the northern part) and Upper (the southern part), so called as the Nile flows from South to North, one of in fact the few great rivers in the world to flow in this direction. The two kingdoms of Upper and Lower Egypt were united around the third millennium BCE, but throughout the dynastic period each region maintained some level of autonomy. The vast and various mythological tradition of the ancient Egyptians reflected this hodge-podge relationship of its peoples and their collective and common experience with the ebb and flow, flooding and recension, of the great river Nile which supported the entire kingdom of Egypt throughout its history, into modern times in fact. Much of their mythology and its underlying belief system in turn, stemmed from and revolved around, the natural and annual cyclical pattern of the flooding of the Nile, governed by the seasons and most prominently by the great disk of the Sun in the sky. [7]

Ra, the Sun god or disc of the Sun, played a prominent role in Egyptian mythos and was one of the most important deities, in various forms and through various epithets and associations, throughout Dynastic Egypt. He was typically portrayed as a man with the head of a hawk or a falcon, and was believed to be the source and sustenance of all life. The governance of Day and Night was supposed overseen by him as he traveled across the Sky, in a boat (think Nile River boat travel) during the Day and then through the Underworld, Duat, at night. To the ancient Egyptians, this mythos explained the great delineation of Day and Night which played such an important role in daily life in ancient Egypt and in all antiquity really.[8]

The concept of the Underworld, and its relation to the sun god Ra as the creator and sustainer of life, was one of the distinguishing characteristics of Egyptian mythos in fact. This daily journey, battle really, of Ra through the Underworld as he battled the forces of darkness or evil in order to successfully make the journey back to the Sky and illuminate the earth again each day is one of the hallmarks of ancient Egyptian mythos. This journey of Ra mirrored the journey of the Soul, Bâ, into the Underworld at death. In the Middle Kingdom, it is Thoth and/or Osiris that becomes associated with this final, or last, judgment of the Soul to determine its ultimate fate, illustrating the role of the Underworld and judgment more generally in not just Egyptian mythos, but also with respect to morality and ethics in ancient Egyptian society – a motif that we see persist in Christian mythos as well in fact.

The primary focus of the Egyptian mythos then, and the intent of most of their rituals and religious ceremonies (consistent with all ancient civilizations really), was to both explain as well as ensure that the natural balance and harmony of nature was preserved. This natural order of the universe was symbolized by the goddess Ma’at, or simply Ma’at, who personified the notion of truth, justice, order, balance and harmony in this world and the next. She was not only the architect of the ordered universe out of its initial watery and chaotic abysmal state, but also the penultimate judge of souls upon death to determine their fate, as illustrated in the famed Weighing of the heart ceremony or ritual where the Soul (represented by the heart (again Bâ) is weighed against the feather of Ma’at, an image which is so prominently illustrated in the Book of the Dead.[9]

Ma’at then came to represent in an abstract sense, truth, balance, order, law, morality, and justice, principles that sat at the very core of ancient Egyptian society which were in turn reflected in their mythos which ultimately held that the Soul was immortal and persisted beyond death, a belief that we find fundamental to almost all ancient mythos, ethics and morality throughout Eurasia in antiquity in fact. Ma’at not only ensure balance and harmony in the sphere of man, but she also ensured balance and harmony in the sphere of the heavens as well, regulating the motion of the stars and the seasons, as well as the actions of the rest of the Egyptian pantheon. In almost all Egyptian cosmogony, it is Ma’at who established order in the universe when the Earth and humans were created. In a somewhat later development, Ma’at was paired with a masculine counterpart Thoth that shared similar attributes.

Thoth was the Egyptian god of wisdom, that during the Ptolemaic Period came to be directly associated with the Greek god Hermes who in Hellenic mythos of course was believed to be the founder and upholder of all knowledge (writing, magic, fire, etc.), the synthesis of which arose the characteristically Hellenic-Egyptian tradition of Hermeticism.

After her role in creation and continuously preventing the universe from returning to chaos, her primary role in Egyptian mythology dealt with the weighing of souls, or judgment, that took place in the underworld upon death, the underworld of the Egyptians akin to the Hades of the Greeks. It was the feather of Ma’at, representing righteousness or justice, that was the measure that determined whether or not a Soul (considered to reside in the heart) of the departed would reach the paradise of afterlife successfully. Pharaohs were often depicted with the emblems of Ma’at to emphasize their role in upholding the laws of the Creator. After the rise of Ra in the Egyptian pantheon, a somewhat later development, Ma’at and Thoth were sometimes depicted together as consorts to Ra. Ma’at, to the ancient Egyptian represented the fixed, eternal order of the universe, both in the cosmos and in human society.

With respect to their creation mythos, or theogony specifically, given the age and variety of inhabitants and peoples of the Nile River delta in antiquity we find are several different theogonic narratives from Dynastic Egypt, each having its source from a different geographical or metropolitan region, and each reflecting a somewhat different perspective on the origin of the universe and the generations, and primary roles, of the gods that came from out of the primordial chaos, or watery abyss, from which the material universe emerged.[10]

The narrative geographically centered in Hermopolis (or Khmun in ancient Egyptian which means “town of eight”) was predominant in Old Kingdom Egypt and is typically referred to as the Ogdoad, or great Eight. In this narrative, there exist eight primordial characteristics of the universe prior to its formation into a creative entity and before the gods come to exist. These four sets of male and female counterparts representing watery abyss itself (Nu & Naunet), eternity or limitlessness (Huh & Hauhet), darkness (Kuk & Kauket) and air (Amun & Amaunet).

The more classic, or orthodox creation myth from ancient Egypt is particularly prominent in the Pyramid Texts and describes the manifestation of Atum as the first deity upon which the world is created. Atum, again closely associated with the Sun as the creative force of the universe, is depicted as emerging, out of these primordial waters – “Nu” or “Nun” – after which the pantheon of gods and their respective elemental characteristics of creation are established. Centered around Heliopolis, the Greek name for the ancient city calling out its close association with the worship of the Sun, we find Atum as representing the deified personification of the great creative force from which all the lesser gods are created. In a fairly loose English rendering of a hymn as it was sung in around 400 BCE in Thebes we find:

At the moment of creation, Atum spoke: I alone am the creator. When I came into being, all life began to develop. When the almighty speaks, all else comes to life. There were no heavens and no earth, there was no dry land and there no reptiles on the land…

When I first began to create, when I alone was planning and designing many creatures, I had not sneezed Shu the wind, I had not spat Tefnut the rain, there was not a single living creature. I planned many living creatures; all were in my heart, and their children and grandchildren.…

Then I copulated with my own fist. I masturbated with my own hand. I ejaculated into my own mouth. I sneezed to create Shu the wind, I spat to create Tefnut the rain. Old Man Nun the sea reared them; Eye the Overseer looked after them…

In the beginning I was alone, then there were three more. I dawned over the land of Egypt. Shu the wind and Tefnut the rain played on Nun the sea…

With tears from my Eye, I wept and human beings appeared… I created the reptiles and their companions. Shu and Tefnut gave birth to Geb the earth and Nut the sky. Geb and Nut gave birth to Osiris and Isis, to Seth and Nephthys. Osiris and Isis gave birth to Horus. One was born right after the another. These nine [ennead] gave birth to all the multitude of the land.[11]

This tradition is sometimes referred to as the Ennead, or great Nine, as Atum begets or gives birth to (or seeds is perhaps the more accurate term) the eight lesser gods – the first pair being Shu (wind/air) and Tefnut (moisture/rain), and the next pair is Geb (earth) and Nut (sky), which in turn give birth to Osiris (overseer of the land of the dead) and Isis (goddess of life and fertility) and then finally Set (god of disorder, or storm) and Nephthys (goddess of order, literally “keeper of the house”), the last four of which provide governance and order to the universal creation.

While this is a fairly late rendition of a much older (Old Kingdom) mythological narrative, we still see the older rendition of the creation of the gods through the self-copulation of the original and primordial god, in this case Atum and the existence of the primordial abyss, Nun and his companion here represented by the “Eye” which preside over the initial generation of gods. Perhaps a later addition to the tale is the association of the word or speech to creation as we can see from the first verse quoted above. But nonetheless here we see the great Eight – the Ogdoad – is preserved here in male/female pairs, the sum total of which provide balance and harmony to the universe and preside over mankind and in particular the land of Egypt.

This Ennead mythos also co-existed or ran parallel with another mythological tradition centered in Memphis which tells the tale of the god Ptah and the universal creation emanating from his heart and mind (the heart being the seat of the Egyptian Soul, i.e. again Bâ) to his speech, or spoken word, where after the world and all its gods are created. From a quotation from an inscription in the tomb of the famed King Tutankhamun, we find the following inscription which is reflective of the ancient Egyptian cosmogonic tradition which centered around Ptah, from whose mouth the universe and all of its gods and creatures sprung forth.

The Lord of All, after having come into being, says: I am who came into being as Khepri (“the becoming one”). When I came into being, the beings became into being, all the beings came into being after I became. Numerous are those who became, who came out of my mouth, before heaven existed, nor earth came into being… I being in weariness was bound to them in the Watery Abyss [Nu]. I found no place to stand. I thought in my heart, I Planned myself, I made all forms being alone, before I ejected Shu, before I spat out Tefnut[12].

Here we see reference to this primordial abyss, represented by water that had both male and female attributes, coming before the generation of the fundamental elements (the gods) of the sky/air and water/moisture. We can also see here perhaps the beginnings of some of the later Hellenic philosophical themes surrounding the formation of the material world from ideas, or forms, or more generally Logos.

What captivates us about ancient Egypt, and is reflected in the text that ancient Egypt is perhaps best known for, The Book of the Dead, is their graphic and symbolic imagery that they created that is associated with death. While this book of myths and stories that was typically read aloud, at least portions, during the burial ceremonies of the upper class, priests and especially – in ornate fashion no doubt – to the pharaohs themselves. The Book has come to more or less be identified with the rituals surrounding death in ancient Egypt, and one of its most prominent features clearly reflects a strong sense of justice and social order, quite reminiscent of the notion judgment in Christianity in fact.

The Book of the Dead however should not be taken out of context within the overall social scheme of daily life to an ancient Egyptian. For this book of mythology as it were, survives because it was inscribed on the tombs of the dead and in the associated inscriptions found with dead rulers and aristocrats. The underlying mythos however, went beyond just death and eternal justice and reflected a broader social appeal, with depictions of various scenes and acts of daily, or “normal” life, reflecting a fairly advanced system of writing that the early Egyptians from the Old Kingdom did not have access to (from which the Pyramid Texts are from).

By the time society around the Mediterranean had advanced to support such grand epic mythological tales that have captivated our collective imaginations for so many centuries, Egypt had already come under strong Greek, Hellenic, influence (and then Roman shortly thereafter), and as such the mythos we see in the Book of the Dead carries with it distinctive Hellenic undertones, or overtones as the case may be. Of course, by the Ptolemaic Period in the last few centuries of the first millennium BCE, the mythos between the ancient Egyptians and the ancient Hellenes had almost completely assimilated, with deities from either tradition having virtual equivalents in the other – with Hermes and Thoth being perhaps the most prominent and notable of examples.

Depending upon the power center of ancient Egypt, there were slight variations of this creation mythos, each of which was centered around a specific metropolitan center off of the Nile which held prominence during the pharaoh’s rule at that time, and each of which ultimately represented the source, and lineage, of his power. Ancient Egypt was made up of Upper Egypt in the South, where ancient Thebes was located, and Lower Egypt to the North where Memphis was located. The prominence of the river, i.e. water, to life in ancient Egypt no doubt is integrally linked to the role that the water plays in its creation mythos, i.e. its cosmogony, manifest as the primal pairing of Nu and Naunet.

The main variants of the creation mythos, by city (using their Greek names) were:

- Hermopolis: the home of the Ogdoador “Eight”,

- Heliopolis: literally the “city of the Sun” (Heliosis the god the Sun in Greek/Hellenic mythos) where Atum, closely associated with Ra as the sun disc, was the leader of the pantheon which in this variant was nine primary deities, i.e. the Ennead,

- Memphis: co-existent with the mythosof Heliopolis except in this variant the universe is created through Ptah, the great craftsman god who, like Plato’s Demiurge, shaped the world through his speech or thought or mind, and lastly

- Thebes: where Amunwas not just a key member of the Ogdoad, or great Eight, but was the force behind all of the other deities and the universe itself.

But from the tombs of the pharaohs, and the written record that accompanied these tombs inscribed on their walls and entranceways, one can see a glimpse of the of the creation mythos, cosmogony, of the ancient Egyptians, which although varied from region to region throughout ancient Egypt, nonetheless still had some very consistent themes throughout, like for example the establishment of universal order, Ma’at (the child of Thoth, the god of the moon, and Ra, the sun god) from the watery, chaotic abyss of Nu (or Nun) and his consort Naunet. From these primary deities, or forces, the universe unfolds, with – like the other creation narratives from Eurasian antiquity in fact – the various universal elements being represented by deities which unfold as part of the theogonic sequence or narrative as it were – Earth (Geb), Sun (Ra/Khepri), Moon (Thoth/ Khonsu), Rain/Water (Tefnut), Wind/Air (Amun/Shu), Sky/Heavens (Horus/Nut), and then the last pairing of Isis and Osiris representing Life/Fertility and Death/Destruction respectively.

It is from the watery abyss, great chasm or void of creation upon which order unfolds, personified in Egyptian mythos as the goddess Ma’at who typically is depicted wearing an ostrich feather in her headdress symbolizing truth and justice, and who sits in opposition to Isfet – the god of chaos, disorder and evil. It is with Ma’at upon which mankind and civilization depends for their proper functioning and balance, encompassing not only the cosmic principle of order and law, but also the law and order of society at large, as well as the normal functioning of the forces of nature. It is Ma’at that shapes the world into its different, ordered creative aspects and which provides the framework within which the other deities are first created and then sustained and balanced to keep the universe together so to speak, and prevent it from falling into chaos.

So Ma’at was a key component of the theo-philosophy, the belief system, underlying ancient Egyptian society and civilization, a notion that helped bind together its peoples along the Nile River valley and helping establish order, justice and harmony not just in the sky and heavens, but also in the sphere of human affairs as well as reflected in the notion of justice or virtue, aspects of which carried the Soul from this world to the next. Ancient Egyptian society was structured to reflect this underlying mythology and belief system, or perhaps better put – the mythos of the ancient Egyptians reflected their way of life and underlying beliefs. These concepts and symbols, personified by the various gods and goddesses and as spoken of in various creation and other myths and takes that explained the natural order of things, its underlying cyclical nature and the fundamental relationship of life and death so eloquently represented in the daily struggle of Ra from the forces of darkness to which life must emerge each day , was ultimately reflected in their worship of the pharaoh as a manifestation of the divine, and in their focus on ritual and sacrifice to the gods to retain this order and balance in their world.

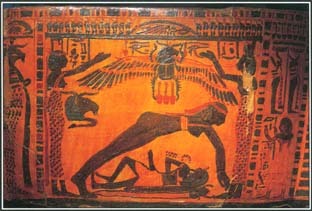

From early Dynastic Egypt as reflected in the Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts, and then later in the New Kingdom as reflected in Book of the Dead, we see a prominence of the notion of the importance of the protection and preservation of the established order of the universe, or Ma’at, that existed in eternal conflict with evil, or darkness, typically drawn as a serpent or snake in the earliest texts, and then later coming to be referred to as I͗zft, or Isfet. By the VIIIth dynasty onward, this serpent which represented the forces of darkness and evil became personified as the god Apep, who became a prominent figure in the New Kingdom mythos, being depicted in a daily epic struggle with the sun god Ra – who represented the forces of light and good – which Ra had to overcome as the Sun passed down through the horizon into the underworld, the place where Apep lie in waiting, in order that the Sun to rise again the following day. Apep was eventually replaced by Set in later Egyptian mythological tradition who came to represent the god of the underworld, or the Hades of the Greek tradition.

We see even in a Coffin Texts inscription specific reference to the requirement of the dead being cleansed of Isfet in order to be reborn in the netherworld, or Duat, speaking to the fundamental and very old ancient Egyptian notion of the universe being a battleground of the forces of good and evil, light and darkness, both at the cosmic level and at the spiritual or individual level.[13] These very same themes can also be found in the Zoroastrian tradition of the Indo-Iranian/Persian peoples to the East where Ahura Mazda and his band of angels are in constant struggle with Angra Mainyu and his band of demons (devas) who represent falsehood, darkness and evil, as well as of course in Christianity, where God and his counterpart the fallen angel Satan are also portrayed as opposing and dueling forces of the world. Another interesting Christian parallel to the Egyptian Isfet can be found in the Judeo-Christian Garden of Eden story where it is the serpent who tricks Adam and Eve into eating from the Tree of Life, plunging mankind out of the Garden and into the mortal world of endless toil, death and suffering.

In some sense, this shifting or changing of mythological emphasis was consistent of the ancient civilizations of the time, before true empires or states ruled whole regions where religious or mythological histories were more standardized or systematized. But regardless of the variety of creation myths that existed throughout ancient Egypt, they all shared a common component; that is the emergence of the world from a primordial watery abyss (referred to as Nu or Naunet in its male and female aspects respectively), quite consistent with what we find in the Hellenic mythological narrative as well as the Hebrew (Jewish) narrative from Genesis.

Regardless of these variations however, in all of the different cosmogonies a consistent undercurrent of the act of creation from the watery abyss (Nu or Nun) and the establishment of order, or Ma’at, can be found, establishing from it the foundations of the physical earth, sky, seasons and basic elements, along with the foundations of civilization itself. The role of the ruler of Egypt in fact was the keeping of this order, the shepherd of Ma’at in the human world as it were, and he (or she) was expected to establish and protect this divine order upon the people in his dominion and throughout the Kingdom of Egypt. In other words, the pharaoh’s role was to interpret and reflect, and to protect and establish, the cosmic order as indicated in the underlying cosmological myth, to the social order – maintaining life and society at large by ensuring that the gods were pleased and sustained with offerings and rituals, and the king’s power originated from his reflection of this cosmic, divine principal and therefore was upheld and respected by the population at large

But despite the different creation myth variants and different versions of the Egyptian pantheon that can be found throughout Dynastic Egypt as the capital shifted between Memphis, Thebes, Heliopolis, and then later in Hellenic Alexandria, there was always present this firm belief in the in the importance of order. Ma’at, in the world, and its epic struggle with chaos and evil, Isfet or Apep, that defined the universe as well as the internal world of the spirit. We see these same themes and notion of eternal struggle not only with Zoroastrianism and Christianity, but also with the Greeks as well, reflected in the epic battle between Zeus and the Titans in the Theogony, where after the Titans were forever bound and chained within Tartarus, the realm of the dead overseen by the Greek god of the underworld Hades, corresponding almost precisely to the Egyptian netherworld Duat and its presider Apep.

[1] Wikipedia contributors, ‘Ancient Egypt’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 15 July 2016, 07:45 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ancient_Egypt&oldid=729888188> [accessed 21 August 2016].

[2] Menes, aka Narmer is the first pharaoh said to have united Upper and Lower Egypt. It is notable that the ancient Egyptians did not use the term pharaoh; this word is taken from the Old Testament context and then later applied to ancient Egyptian history. King is a more appropriate term but we will use King or pharaoh interchangeably throughout. For more information on the etymology and history of the term pharaoh see http://ashraf62.wordpress.com/ancient-egypt-knew-no-pharaohs/.

[3] The word hieratic was first used by the Christian theologian Clement of Alexandria who lived and wrote in in the late 1st and early 2nd century CE and is derived from the Greek word hieratika which literally means “priestly writing”.

[4] Demotic was succeeded by the Coptic writing system/alphabet (and the Coptic language which it is designed to render) which started to take root in the 3rd century CE and is still in use in some Egyptian churches and other places today. The Coptic alphabet is based upon the Greek alphabet with strong Demotic influence.

[5] The Book of the Dead in Egyptian is actually titled, in Egyptian, rw nw prt m hrw which is more accurately transliterated into English as the “Book of Coming Forth by Day” rather than the more popular name it has been given by modern scholars and historians, the Egyptian Book of the Dead.

[6] From http://www.ancient.eu/image/113/. Original image by Jon Bodsworth and uploaded by Jan van der Crabben, published on 26 April 2012 in the Public Domain.

[7] The Nile is only main river system that flows from south to north and its name is derived from the Greek “Nelios”, meaning River Valley.

[8] Note the similarities to the Greek god Apollo who was depicted as riding a chariot through the sky and who also symbolized the sun, light and knowledge (life).

[9] See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Ma’at’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 18 June 2016, 05:43 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ma’at&oldid=725837786> [accessed 21 August 2016]. The notion of Ma’at is quite similar in fact to the Hellenic concept of Logos), at least as a more primitive personified form and arguably is the source from which this all important Hellenic philosophical principle originates from.

[10] E.J. Michael Witzel speaks to four ancient Egyptian cosmogonic traditions from Heliopolis, Memphis, Thermopolis and Thebes. The Heliopolis version he refers to as the most “orthodox”, dating from the 5th dynasty or the middle of the third millennium BCE. See also Wikipedia contributors, ‘Ancient Egyptian creation myths’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 4 July 2016, 18:40 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ancient_Egyptian_creation_myths&oldid=728334663.

[11] Old Testament Parallels: Laws and Stories from the Ancient Near East. Victor H. Matthews and Don C. Benjamin. 3rd edition published by Paulist Press, NY/NJ 2006 pgs. 8-9.

[12] Quoted from A Piankoff’s The Shrines of Tut-ankh-amon, excerpt from The Origins of the World’s Mythologies, E. J. Michael Witzel 2012; pg. 113/114. Note the translation from hieroglyphs to English is a wholly different exercise of the translation from Greek or certainly Latin to English where grammar (subject and object and verb transitions) as well as direct word etymology is absent.

[13] Coffin Texts 335a, reference from Rabinovich, Yakov. Isle of Fire: A Tour of the Egyptian Further World. Invisible Books, 2007 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isfet_(Egyptian_mythology).

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!