The Ancient Hebrews: The Tanakh, Torah and Five Books of Moses

As a specific example of how a word, a concept, can be disfigured and lose its fullness and richness of meaning as it moves through successive languages of translation and cultural evolution, let’s look at how the Hebrew word Torah, which carries so much significance in the Jewish community, has come to be more understood as law or custom rather than the full revealed and complete theological and spiritual framework that it implied to not just its original author, Moses, but also to the audience to which the treatise was originally compiled and transcribed in the ancient Hebrew.

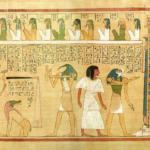

For example, the Torah is sometimes loosely translated into English simply as “law” or “the law”, coming from the Greek word for law, or “Nómos” (νόμος). Nómos is a fairly loaded term in Greek antiquity that plays a very prominent role in classical Hellenic philosophy. To the Hebrews, their governance structure, the guiding social structure of their people, is established and rationalized via the narrative and stories in the Torah, hence the inclination to use the Greek Nómos as a transliteration of the underlying purpose of the text. In many respects, this concept is analogous to the Ma’at of the ancient Egyptians which is the deity and notion that provides the rational foundation, and mythological tradition, that provides the basis for balance and harmony, justice and “law”, in human affairs.

The word “Torah” in Hebrew is derived from a root that means to “guide” or “teach”, so a good translation for the word directly into English might be “teaching”, “doctrine”, or “instruction”. But in the Greek Septuagint, which was transcribed in the first or second century BC in old Koine Greek by a group of Jewish scholars at the behest of Ptolemy II (309 -246 BCE) in Alexandrian Egypt which by that time had been infused with Hellenic culture. In the Septuagint, or simply the LXX, the Hebrew word “torah” was translated into Greek to as Nómos, which in fact is the Greek word for “law” or “custom”. In Hellenic intellectual and philosophical circles however, Nómos had a much more complex and rich meaning. A Greek Orphic hymn to the god Nómos illustrates its depth of meaning of this concept to the Ancient Greeks, a tradition that undoubtedly was in the minds of the translators of the LXX:

The holy king of gods and men I call, heavenly Nómos, the righteous seal of all: the seal which stamps whatever the earth contains, and all concealed within the liquid plains: stable, and starry, of harmonious frame, preserving laws eternally the same. Thy all-composing power in heaven appears, connects its frame, and props the starry spheres; and unjust envy shakes with dreadful sound, tossed by thy arm in giddy whirls around. ‘Tis thine the life of mortals to defend, and crown existence with a blessed end; for thy command alone, of all that lives, order and rule to every dwelling goes. Ever observant of the upright mind, and of just actions the companion kind. Foe to the lawless, with avenging ire, their steps involving in destruction dire. Come, blest, abundant power, whom all reverse, by all desired, with favouring mind draw near; give me through life on thee to fix my sight, and never forsake the equal paths of right.[1]

So Nómos then, at the time that the Hebrew Old Testament was transcribed into Greek, is very much akin to the Ma’at of the Egyptians, the personification of which becomes and is synthesized with the (Orphic) Greek notion of Nómos. Having said that, given how steeped in tradition and custom the Jewish faith is, still following today in many respects the ways and customs of the ancient Hebrews that was codified and captured in the teachings of Moses, one can certainly see why the Greek Jewish scholars in the 3rd century BCE used this word.

The translation of torah then Nómos, and in turn to the its Latin successor lex, which has a much more direct association with our modern conception of “law”, has historically given rise to the notion that Torah signifies or emphasizes laws or customs rather than the implying the complete historical and socio-religious narrative captured in the scripture of the Jewish faith, i.e. “teaching” where torah is not just the law that governs human affairs but the law, and underlying order, of the cosmos which in turn human affairs should be aligned and consistent with.

This history or etymology of the phrase, “Law of the Hebrews” which we find in modern readings of the subject and is associated with the Torah illustrates how the richness of meaning and fullness of the original word in the original language developed over the centuries and effectively “stuck”. But the true meaning of the word and its relation to the Jewish faith in general is best understood when looking more closely at its etymology. Words and ideas lead to understanding, or misunderstanding as the case may be, just as Plato has told us.

Christianity and Islam are the most widespread and influential religions in the world today by any measure, and both sprung from and were heavily influenced by the monotheistic traditions, and metaphysical and philosophical systems, that preceded them – most notably Judaism, but Zoroastrianism as a close and far less recognizable second. These influences are evident by the obvious incorporation of Judaic mythology and tradition directly into the canonical version of the Bible as we know it today, along with the explicit references to the Abrahamic prophetic lineage, including Jesus himself, in the Qurʾān. Less explicitly however, we find the incorporation of many of the theological themes and divine principles of Zoroastrianism integrated into Christian belief systems, perhaps not surprisingly so given the Persian influence in the region that Jesus was born and taught in.

The written tradition upon which the Jewish religion, or religion of the Hebrews as it was called in antiquity, is based upon what is called in Jewish circles the Tanakh, which corresponds to the canon of the Hebrew Bible, what we have come to know as the Old Testament, which includes the Torah, or Books of Moses”. The Torah represents the heart of the Jewish written and historical tradition and rests squarely on the writings and teachings attributed directly to the prophet Moses, a pseudo-mythological and historical figure who lived, if we believe in his historicity at all, sometime in the middle of the 2nd millennium BCE.

The written tradition also includes “non-canonical” writings, specifically a companion tradition of rabbinic commentary which is called the Talmud which consists of commentaries upon the Jewish faith on topics ranging from law, ethics and customs, theology and philosophy, as well as history and mythology, and provides the basis, along with the Tanakh, for Jewish law. According to the Talmud, much of the contents of the Tanakh were compiled by the “Men of the Great Assembly” in the middle of the 5th century BCE. While this date of composition is the topic of much debate in modern scholarship, most scholars of ancient history would agree that the Tanakh in its present form was shaped for the most part in or around the 2nd century BCE.[2] The origins of some of the writings however, particularly in Genesis, clearly have origins that can be placed much further back in antiquity.

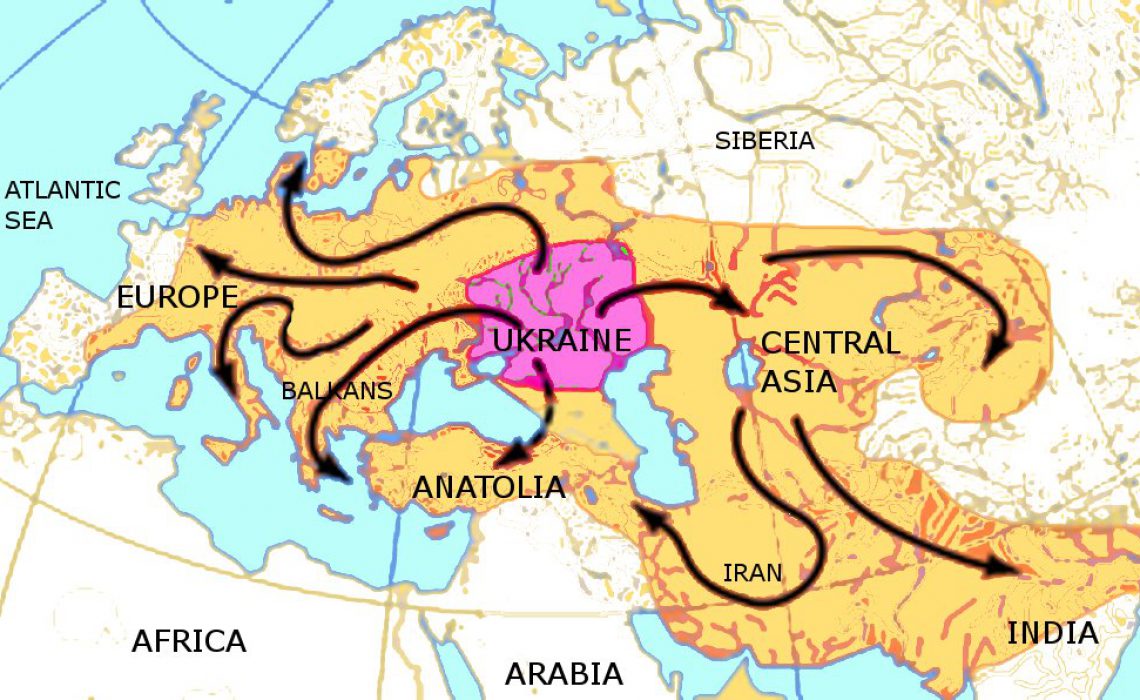

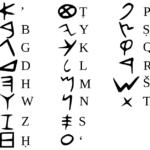

The Tanakh and Talmud were mostly written in Biblical Hebrew, although some parts written in Aramaic, a closely related Semitic language. Ancient Hebrew and Aramaic (as well as Arabic) are in the Afro-Asiatic/Semitic family of languages, a distinct branch of the language tree from the Indo-European languages from which almost all modern European languages descend, a branch which includes English of course.[3]

Judaism has its roots deep in ancient history, and in many respects represents one of the oldest and most well documented ancient theological traditions. Some of the historical narrative of the Old Testament can be placed well back into the second millennium BCE judging by the historical evidence from within the text itself, as well as corroborating archeological and other historical (written) evidence which supports at least some of the historical narrative in the text.

Judaism today, and from its outset upon its founding by the pseudo-historical prophet Moses, teaches that there is only one God and no other God is to be worshipped other than He, namely Yahweh and that he, through Moses and the line of prophets descendant from him, has outlined very specifically how the Hebrews should conduct themselves and how they should organize and structure their faith and worship. The Jewish mode of worship, its religious practices and ritual, and even its ethical and moral precepts, are based upon both this written tradition as encapsulated in the Tanakh and Talmud but also a vibrant and lasting oral tradition as well which is referred to as the “Oral Torah” and is to be studied in conjunction with the written word, with the assistance of a competent Hebrew scholar and teacher (i.e. a Rabbi) in order for full appreciation and understanding of the teachings to be realized.

The Tanakh is broken down into three different parts or sections, almost all of which were included in the Christian Biblical canon as part of what we have come to know as the Old Testament. We first have the Torah, or again the “teaching” which is directly attributed to Moses, then the Nevi’im or “prophets”, and then finally the Ketuvim or “writings”, the sum total of which represents the written teachings of the ancient Hebrews which is looked upon even today by the Jewish community as the guiding principles for the leading of a good and just life in the eyes of God (Yahweh).

The Torah consists of five books, all of which are attributed to Moses and all of which are believed by modern scholars to have been written by one individual – hence the Five Books of Moses’. In the Hellenic philosophical tradition, we find these books referred to as the Pentateuch, literally “five books” in Greek and as they come down to us through the canonization of the Bible, we have come to know these as these books as the first five books of the Old Testament, namely Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In Hebrew, the original language of the Torah, each of the books is known by the first prominent word or phrase in each book, a custom that was common in antiquity, and sometimes in the Hebrew intellectual and theological tradition we see the books referred to by their Hebrew names which are:

- Bereshit (בְּרֵאשִׁית, literally “In the beginning”), i.e. Genesis

- Shemot (שִׁמוֹת, literally “Names”), i.e. Exodus

- Vayikra (ויקרא, literally “And He called”) i.e. Leviticus

- Bəmidbar (במדבר, literally “In the desert [of]”), i.e. Numbers

- Devarim (דברים, literally “Things” or “Words”), i.e. Deuteronomy[4]

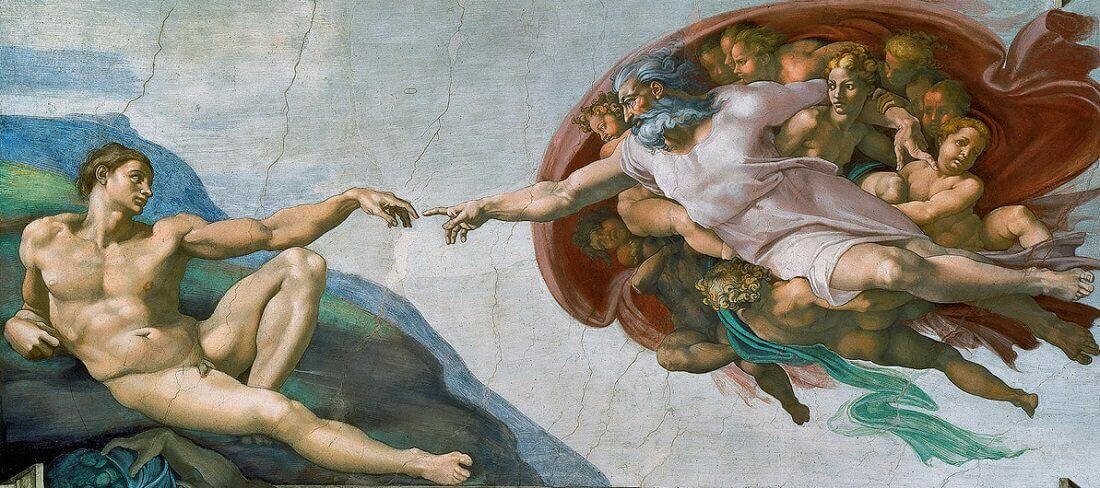

In these books, Moses tells the story of the creation of the world and mankind, down through the origination and lineage of the Hebrews, culminating in a detailed pseudo-historical account of the life of Moses himself and the famed story of the leading of the Hebrews out of Egypt by Moses as told in Exodus. It starts however, in the first few verses of Genesis, with the famed creation of the world in 7 days, perhaps the most well-known and commented on passage from any text in the history of mankind:

1 In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.

2 And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.

3 And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.

4 And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.

5 And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And the evening and the morning were the first day.

6 And God said, Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters.

7 And God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament: and it was so.

8 And God called the firmament Heaven. And the evening and the morning were the second day.

9 And God said, Let the waters under the heaven be gathered together unto one place, and let the dry land appear: and it was so.

10 And God called the dry land Earth; and the gathering together of the waters called the Seas: and God saw that it was good.

11 And God said, Let the earth bring forth grass, the herb yielding seed, and the fruit tree yielding fruit after his kind, whose seed is in itself, upon the earth: and it was so.

12 And the earth brought forth grass, and herb yielding seed after his kind, and the tree yielding fruit, whose seed was in itself, after his kind: and God saw that it was good.

13 And the evening and the morning were the third day.

14 And God said, Let there be lights in the firmament of the heaven to divide the day from the night; and let them be for signs, and for seasons, and for days, and years:

15 And let them be for lights in the firmament of the heaven to give light upon the earth: and it was so.

16 And God made two great lights; the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night: he made the stars also.

17 And God set them in the firmament of the heaven to give light upon the earth,

18 And to rule over the day and over the night, and to divide the light from the darkness: and God saw that it was good.

19 And the evening and the morning were the fourth day.[5]

In this creation narrative, one that no doubt has shaped the theological beliefs of Western society for some 2000 years at least, we have the formulation of structure and time as underpinnings for the story itself – God creates the world in seven days – but we also see the emanation of various basic universal elements, and then the heaven and earth itself, that emerge from the “primordial waters”, a very old cosmological motif that is virtually ubiquitous in ancient civilization of the Middle, Near and Far East.

But core to this narrative in fact, and underlining the Judeo-Christian worldview (which in turn is shared by the Muslim tradition despite its basic disagreement with its Judeo-Christian brethren on the relative importance of various prophets and basic theological stances such as the Holy Trinity and its implications on the underlying unity of God/Allāh) is the role of God, the grand creator, preserver (and ultimate destroyer) of not just humanity but the universe itself. In this tradition we do not have any thread of philosophical questions with respect to the unity of existence, duality from unity or even any epistemological questions as to what could be known or who it could be known by (the chicken and the egg question so to speak), we simply have a creation story in succinct form which lays out what was created, when, by whom in quite literal fashion – laying the groundwork for a moral and ethical framework which is just as unforgiving as it were, given its lack of philosophical foundations, despite the longstanding work done by the Greco-Roman philosophical tradition to facilitate these philosophical lines of questions.

Genesis then is the first part of the Torah, the scripture of the Hebrews within which we find not only the famed story of the creation (two of them actually), but also the famed legend of the Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden and their fall from grace via the temptations of the great snake, as well as the story in Exodus of the giving of the Ten Commandments to Moses by Yahweh after his people had been led out of tyrannical Egypt through various miracles performed by Yahweh on behalf of their “chosen” people, and many of the other legendary tales that have come to represent the mythos of the modern day Judeo-Christian (and again to a lesser extent Muslim) world. It is in the Pentateuch where we find the historical and theological underpinnings of the Jewish faith, the philosophy of the ancient Hebrews as it were.

The Nevi’im, or “Prophets”, consists of eight books and cover the history of the Jewish people from the time Hebrews enter the land of Israel until the time of Babylonian captivity under the prophet Judah in the early 6th century BCE. Books of the Nevi’im include Joshua, Judges, Samuel I & II, Kings I & II, Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel.

The Ketuvim, or “writings”, sometimes referred to by the Greek name Hagiographa, consists of eleven books which include the Book of Psalms, Proverbs, Job, Ecclesiastes, Daniela and Chronicles among others. Two of these books are the only ones were that have significant portions written in Aramaic rather than Hebrew, and some of the books are in poetic form rather than prose which is standard for the rest of the Torah. The contents of the Ketuvim are considered to be later editions of the Torah and although not as authoritative as the “teachings” are nonetheless considered instructive and crucial to understanding Hebrew philosophy (the Jewish faith) and were therefore canonized along with the contents of the Nevi’im and Books of Moses.

With respect to the underlying history and evolution of the Torah as a written textual, and associated oral, tradition of the ancient Hebrews, scholars best guess for the actual compilation of the (earliest) material is, at the earliest, in the middle of the first millennium BCE. Given the historical material in these works, and there is much historical material that can be corroborated with other ancient authors, our best guess as to when Moses actually lived, as the historical figure rather than the author, is at least a thousand years or so before the earliest parts of the Torah was compiled, leaving plenty of room for doubt and question as to whether or not a) Moses was the author of the Books attributed to him, or b) what the actual socio-political factors were that drove its adoption and prevalence among the ancient Hebrews for a thousand years after Moses died and handed over the care for the Jewish people (and state) to his successor Joshua.

Ancient oral traditions were strong no doubt, but how much was lost or transformed within these 1000 years before the Old Testament was officially compiled and transcribed by the Men of the Great Council in the 5th century BCE and the centuries thereafter? This oral tradition problem, or prophetic separation if we may coin a term, existed in almost all religious systems, at least the ones that are most commonly practiced today. Even the Qurʾān was not written down by Muḥammad himself, implying that even if we leave aside the problems of language and socio-political interpretation of the text, we’re still left with some level of prophetic separation, the time period and possible miscommunication of ideas between what the prophet actually said, or communicated, and what was actually written down, or transcribed. This notion of prophetic separation is reflected in the Islamic tradition by for example slightly different versions of the Qurʾān that have persisted down to present day.

As far as authorship goes for the Pentateuch itself, it is very much debated by modern scholars and theologians as to whether or not it can be established that Moses was in fact the true author. Having said that it is clear that the five books attributed to Moses provide a consistent and cohesive narrative however and that would seem to indicate that there was a single author or editor who compiled at least these 5 books. Whether or not this was actually Moses is a different question entirely of course. There are however many references in the Books of Moses themselves, as well as throughout the rest of the Old Testament (and even in the New Testament), that indicate that Moses is in fact the author in question, but identifying whether or not this individual was in fact the historical Moses or some other later individual who later wrote down the narrative remains a matter of speculation. The tradition of the compilation of ancient material from a long standing oral tradition associated with an historical figure from many generations prior to authorship is of course a common practice in antiquity – the Vyasa of the Vedic tradition or Zarathustra of the Avestan lore, and even Orpheus being from the Greek tradition being prime examples.[6]

The core of the Jewish faith and tradition however rests in the Torah, and from the Jewish vantage point its author, at least the first five books, is Moses. The Moses to whom Yahweh (Elohim) revealed his message to directly, which was captured in the Torah, in both written and oral form, and passed down through the ages via the Rabbinic scholars and teachers into present day. According to the Jewish tradition, the contents of the Torah were “revealed” to Moses by Yahweh himself, in the very same way the Zoroastrian, Christian and Islamic faiths had at their core the belief that their scripture was revealed by the one true God of their respective faiths through their respective prophets – Zarathustra, Jesus and Muḥammad respectively[7].

The Jewish tradition, referred to in antiquity as the religion of the “Hebrews”, was born out of the eastern Mediterranean and therefore not surprisingly shows marked Sumer-Babylonian influence, influence that has now been well documented by modern scholarship. This influence can be seen most prominently in the mythology and historical narrative laid out in Genesis (“in the beginning”), where the stories of creation and fall from grace from the garden of Eden bear striking similarities to motifs and mythological narratives that we know were commonplace in the Assyrian/Babylonian civilization that lay just to the East. The story of the Noah and the Great Flood and the preservation of mankind from the wrath of God also in Genesis can also be found in the mythos of the Near East within the great Epic of Gilgamesh.

The Sumer-Babylonian/Assyrian civilization from which these stories clearly originated, or at least from which we have the earliest evidence of their existence, preceded the compilation of the theo-philosophical tradition of the Hebrews by some centuries, millennia even, but at the same time provides evidence for the cultural milieu within which Moses the prophet lived and transcribed the ancient Hebrew narrative in what has come down to us as the Pentateuch, surviving to this day as one of the great cultural heritages of the West in the canon of the not just the Hebrew Bible but the Christian Bible as well as the Old Testament, incorporating much if not all of the ancient Hebrew mythos.[8]

So with the Jewish monotheistic tradition then, we see some outside influences on the scripture itself from Sumer-Babylonian and other Canaanite mythos, but the faith, as with all of the Abrahamic traditions, is centered around the belief in the direct revelation of the Word of God to its prophet, Moses, and the subsequent transmission and codification of this revelation to its people. But what should not be lost, and is true most certainly for Christianity and Islam as well, is that the canonization and standardization of the faith and its practices down through the centuries after the passing of its prophet, was intended to unite its people, and somewhat distinctly for the Jews, to legitimize and establish their ancestral homeland in Israel.

But with Moses and Judaism, as was the case in each of these other ancient monotheistic traditions, the prophet taught the message of the one true God to students and followers, their people, and then generations after these teachings were transcribed from the oral tradition into written form in order to unite its people, each revealed tradition transcribed in the language that was prevalent in the civilizations within which the religions flourished. For the ancient Jews, it was Hebrew, for the Zoroastrians it was Old Avestan, for the Indo-Aryans it was Vedic Sanskrit and for the Christians it was Greek and then Latin, and for the Muslims it was Arabic. The language within which each of these ancient religious frameworks was documented reflected and mirrored the civilization within which they took root, each civilization unique in its own way and this uniqueness was reflected in the prevalent language and form of writing which was most common place, for language and civilization evolved together no doubt.

[1] Orphic Hymn 64 to Nómos (trans. Taylor) (Greek hymns C3rd B.C. to 2nd A.D.).

[2] There is also credible historical evidence at least that indicates that the final Jewish canon in its present day form was still as yet finalized by the first century CE, as reflected for example in the writings of Jewish historian Josephus among others, see Wikipedia contributors, ‘Tanakh’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 30 July 2016, 02:19 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Tanakh&oldid=732165354> [accessed 23 August 2016]

[3] Ancient Hebrew and Aramaic were written in an alphabet system that was closely related and derived from the Phoenician alphabet system, the very same alphabet system and form of writing for Greek, Arabic, and Latin. The lineage of these different ancient languages and their corresponding writing systems within which their respective languages were encoded as it were is important because it provides us with some insight as to the challenges in translating the Hebrew text into English, sometimes through the intermediary language of Greek to which the Old Testament Hebrew texts were translated in 3rd century BCE Hellenic Egypt (i.e. the Septuagint).

[4] Wikipedia contributors, ‘Tanakh’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 30 July 2016, 02:19 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Tanakh&oldid=732165354> [accessed 23 August 2016].

[5] King James Bible. Genesis 1-19.

[6] See http://bible.org/seriespage/introduction-pentateuch for a fairly detailed account of the scholarly debate and evidence of the authorship of the Pentateuch.

[7] Vedānta as reflected in the Upanishads and the Vedas holds the same belief, namely that the scripture was divine revelation and therefore was to be held sacred.

[8] The story of Noah and the flood in the Torah is very similar in terms of the narrative as a whole as well as some of the specific features of the tale in the Epic of Gilgamesh, perhaps the most prevalent and popular of the Sumer-Babylonian myths from antiquity. Also, the creation of the world as laid out in Genesis, as well as the myth of the Garden of Eden can also be found in Sumer-Babylonian mythos. For a very detailed analysis of the Garden of Eden’s antecedents in Sumer-Babylonian mythos, as well as the potential origins of Jewish Kabbalistic practices from the Babylonian “Tree of Life”, please see the article by Simo Parpola on The Assyrian Tree of Life: Tracing the Origins of Jewish Monotheism and Greek Philosophy published in the Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 52, No. 3 (July 1993), pgs. 161-208 published by the University of Chicago Press.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!