Buddhism 101

Origins of Buddhism

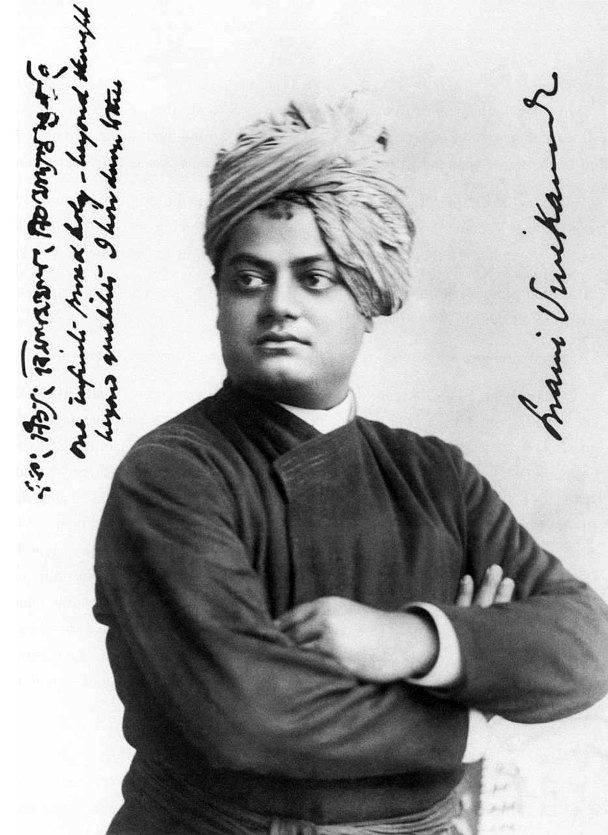

Buddhism originated out of the Hindu and Vedic culture just as Christianity emerged out of and in reaction to orthodox Judaism. The historical figure we know today as Buddha was raised on the northern Indian/Nepal border in the foothills of the Himalayas as a prince from an affluent ruling family, living and teaching somewhere between the end of the sixth and early part of the 4th centuries BCE but dated by most scholars to have lived and taught in the 5th century BCE.

What we know about the historical figure named Siddhartha Gautama who later became known as Buddha is from texts written in Pali (an extremely close relative to Sanskrit[1]), and other somewhat later Sanskrit, Tibetan and Chinese texts that were transcribed no sooner than some 2 or 3 centuries after his death and in some cases not fully codified until the 2nd or 3rd century CE. The texts cover what is supposedly his direct teachings to not just householder disciples but also covers specific guidelines and rules for the establishment of a monastic order as well, along with some materials (written in the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE) which outline the basic facts of his life, the latter being interspersed with some basic facts as well as a variety of mythical accounts that had become associated with the historical figure who is attributed to the founding of one of the world’s greatest and lasting religions that still thrives to this day.

The mythical narrative surrounding the birth, life and death of the Prince Siddhartha is consistent with the narratives of most pre-historical heroic figures (Jesus, Hercules, etc.) and starts with stories of his immaculate conception into a ruling family in the foothills of the Himalayas in Northern India. It is said that upon his birth, which his mother did not survive, he was visited by a great sage who predicted that he would either be a great ruler of men or a great religious teacher and reformer (holy man).

His early childhood and young adulthood was spent living the life of luxury within the confines of multiple palaces and exposed to all the pleasures and luxuries of life. It is said that his father, given the prophecy upon his birth, took great pains to shelter him from any outside influences that would expose him to the suffering and harsh realities of the world. He is said to have married and had a son (Rahula) and spent 29 years in this sheltered and elaborate existence as a great prince with no want or desire left unfulfilled.

After this illustrious and heavenly upbringing it is said that one day he left his palace to view his subjects first hand, despite the misgivings and sheltering instincts of his father, upon which he saw first and old man on the verge of death, then a diseased man in great suffering followed by the corpse of a dead man and lastly by an ascetic monk, all of which completely transformed his view of the world, drove him to great compassion for the plight of his people and inspired him to renounce his royal pedigree and live the life of a wandering monk to search for Truth and the secret to the end of suffering, leaving his wife and child behind.

Siddhartha then spent the next several years practicing various forms of yoga and asceticism to try and find the path to enlightenment and an end to suffering, each successive path and each successive teaching yielding no answer to what he considered to be the basic problem of life for all people and which he saw as his ultimate goal and purpose. It is then said that after practicing austere forms of renunciation and deprivation, he followed settled down under a Bodhi tree (believed to be in Bodh Gaya, India) resolved to sit in deep meditation until he solve the problem of human suffering or died trying.

From an historical context Siddhartha Gautama life and teaching represents one of the many theo-philosophical streams of thought that emerged in the Indus Valley region at the time as alternatives to the older Vedic religion that was steeped in ritual and dogmatism. These various religious movements are sometimes grouped together as Sramana and gave rise to not just Buddhism, but also the Upanishadic tradition of Vedanta, Jainism and later the Yogic philosophic traditions, all descending from the Vedic/Hindu theo-philosophical tradition of antiquity but all rejecting many of its orthodox positions regarding caste and ritual and all for the most part sharing core philosophic themes and terminology such as samskara, the psychology underpinning the cycle of birth and death, karma and the laws of action which underpin Indian ethics even to this day, and the possibility and reality of moksha, or liberation.

After supposedly sitting in deep meditation for some 49 days, being tempted during his practice by various demons and gods with all sorts of worldly temptations to lead him astray (think Jesus’s 40 days and 40 nights in the desert having been tempted by Satan), at the age of 35 Siddartha Gautama achieved Enlightenment and arose as the Buddha which we know his as to this day. Upon emerging from this deep meditative and transformative experience, which was supposed marked by a great earthquake when his state of enlightenment was achieved, the Buddha had complete understanding and knowledge of not only the source of the world’s suffering but also the path to rising above it so to speak, to reach a state of nirvana which would yield an end the seemingly endless cycle of birth, suffering, and death which plagued mankind since time immemorial. Although initially reticent to teaching this new found knowledge to the rest of mankind thinking that they were too steeped in ignorance and desire to every understand what he had come to realize under the Bodhi tree, he was supposed convinced by one of the great Indian deities Brahma Sahampati to at least try for the good of mankind.

And thus began the 45 years of teaching of Buddha, what is sometimes referred to as his Dharma or “way” as a complete explanation and exposition of the laws of nature and how they applied to the problem of human suffering and how the great cycle of birth, disease, decay and dying could be overcome by proper understanding of “reality”, or the shedding of ignorance “vijnana” which to Buddha was the ultimate source of suffering – ignorance of the true nature of the self and consciousness, i.e. that it was an illusion and that it does not in fact exist.

Buddhist Scripture and Philosophy

When analyzing the teachings of Buddhism, as reflected in the various textual sources which were compiled by his followers sometime after his death, we are left with very similar challenges and pitfalls when studying the philosophy of all of the great teachers in antiquity. While we can optimistically assume that his precise teachings and doctrines, words and phrases and terminology , were faithfully transcribed by his followers even if several generations of teacher and student transmission existed before any of the actual texts which codify his teachings were transcribed, we still nonetheless have to try and extract what he actually said and taught from the extant literature – for the texts were written in a variety of languages that a) in all likelihood do not reflect the actually language that he spoke, and b) we do know that he did not leave any written materials behind himself.

The most authoritative and oldest textual tradition surrounding Buddhism is the Pali Canon, also referred to sometimes by the Sanskrit Tripitaka, meaning “three baskets” denoting the three main treatises that make up the ancient scripture that is written in Pali, an ancient script very closely related to Sanskrit. According to almost all scholarly accounts, it is the Pali canon that represents the oldest authoritative Buddhist scripture. This strain of Buddhism represents what is referred to as Theravada Buddhism.

According to tradition, the transcription of the Pali Canon is the result of the Third Buddhist Council that was convened at the behest of the pious Indian emperor Ashoka Maurya (304-232 BCE) who ruled much of the Indian subcontinent in the third century BCE. His intent for convening the council, much like the Christian councils that were convened in the 3rd century CE onward, was to standardize the teachings, texts and some philosophical elements of Buddha’s legacy from amongst the various factions that had sprung forth after Buddha’s death, leading to the existence of a variety of teachers and philosophic schools who disagreed on many aspects of the Buddha’s message and precepts.

As the tradition has it, the council lasted nine months and consisted of senior monastic representatives from all around the emperor’s kingdom who debated various aspects of Buddhist doctrine, culminating in the canonization of the scripture (the Pali canon) and forming the foundations of Theravada Buddhism. After the council it is said that the emperor dispatched various monks who could recite the teachings by heart to nine different locations throughout the Near and Far East, laying the groundwork for the spread of Buddhist teachings and philosophy not just in the Indian subcontinent, but throughout the ancient world as far East to Burma and even as far West to Persia, Greece and Egypt.

The Tripitaka contains three major sections, the Sutra Pitaka (Sutta Pitaka in Pali), the Vinaya Pitaka, and the Abhidharma Pitaka (Abhidhamma Pitaka in Pali). The Sutra Pitaka is the oldest of the three parts of the canon and is said to have been recited by Ananda, Buddha’s secretary at the First Council, a meeting of five hundred disciples of Buddha shortly after his death to compile his teachings. The Sutra portion of the Tripitaka contains discourses in dialogue form between Buddha and his disciples and other contemporary figures on a variety of doctrinal and spiritual questions within which the philosophical heart of Buddhism is contained. Another disciple of Buddha named Upali is said to have recited the Vinaya portion of the Tripitaka which deals mostly with rules governing monastic life, reflecting the strong undercurrent of renunciation and monasticism which has been a part of Buddhism from the very beginning. The Abhidharma portion of the Pali canon is the youngest material and supposedly reflects the Buddha’s teachings to various deities in heaven during the final period of his Enlightenment and deals with various philosophical and doctrinal issues which help elucidate the some of the more esoteric and obscure aspects of the scripture.

It is from the Sutra portion of the Pali canon that we can glean the core of Buddha’s teachings to his disciples as it’s clear that the Vinaya and Abhidharma sections contain somewhat later material relative to the Sutra Pitaka. It is divided into five sections of sutras which are grouped as nikayas, or “collections” – the Digha Nikaya or “Long Discourses”, the Majihima Nikaya or “Middle Discourses”, Samyutta Nikaya or “Connected Discourses”, the Anguttara Nikaya or “Numerical Discourses”, and the Khuddaka Nikaya or “Minor Collection”.

The other main thread of Buddhism which continues to thrive today is Mahayana Buddhism, of which the more widely known schools of Zen and Tibetan Buddhism are representative. Mahayana literally means “Great Vehicle” in Sanskrit and focuses and builds upon the Buddhist monastic tradition as articulated in the Tripitaka and establishes the path, rules and practices for those who want to pursue enlightenment for the good of all sentient beings as Buddha himself did, what are referred to as bodhisattvas, or “enlightened beings”, in the Mahayana tradition. Although the Mahayana schools do not necessarily differ from the Theravada tradition which precedes it historically in terms of basic philosophical tenets and practices, it nonetheless developed a unique and relatively independent scriptural and philosophical tradition which codified and institutionalized specific doctrines, teachings and practices for the pursuit and attainment of enlightenment, what perhaps Buddhism in modern parlance is best known for.

The essence of Buddhism in all schools however is to be found in the Eightfold Noble Path and the Four Noble Truths, the latter of which outlines the true nature of reality and the causes of suffering and the former which addresses directly the path to end such suffering permanently. Buddhism does not lay out a philosophic discipline per se, nor does it lay out any systemic laws or beliefs as is characteristic of the Abrahamic religions, but instead lays out some basic fundamental precepts about the nature of life and reality from which it establishes a path, the so called “Middle Way”, to rising above the seemingly endless trials and tribulations of life, resting on the fundamental assertion that not only is enlightenment possible, but that there is a specific path which when followed rigorously will lead to nirvana which in Buddhism is the ultimate goal of all sentient life.

Buddhist Metaphysics and Psychology

It is said that Buddha first taught the Noble Eightfold Path and the Four Noble Truths to his five companion ascetics just after attaining enlightenment as recorded in the Dharmacakra Pravartana Sutra, or The Setting in Motion of the Wheel of Dharma as the title is translated into English, a set of sutras which can be found in the Sutra Pitaka portion of the Pali canon. In this teaching, Buddha is addressing his five fellow renunciate ascetics with whom he practiced sadhana (religious rites and practices) with, and he lays out his basic philosophy as it was revealed to him when he achieved enlightenment. He rejects the two extremes of complete self-indulgence and total self-denial (renunciation) and puts forth a “middle way”, what has come to be known as the noble eightfold path, as the means to salvation and cessation of suffering.

After laying down the middle way, Buddha describes the nature of reality, or the Four Noble Truths, the proper understanding of which underpins the “right view” portion of the Eightfold Noble Path. These four truths, the pillars of Buddhist philosophy, can be summarized as follows:

- The Truth of Suffering: that the basic nature of life is characterized by varying types and degrees of suffering (duhkha), sometimes alternatively translated as

“unsatisfactoriness”. Suffering in this context involves the mental and physical pain associated with the process of being born, being subject to disease and illness and ultimately death, as well as the stress and anxiety associated with attachment to feelings, objects and emotions that are in a constant state of change – the Buddhist notion of impermanence (anitya) and attachment or grasping (upadana). - The Truth of the origin of suffering: that suffering has an ultimate source and it comes from the incessant craving or attachment (raga) of objects of desire and its conjugate the aversion of fear of undesirable objects, (dvesha) ultimately stemming from ignorance (avidya), or wrong knowledge, of our ideas of self and reality.

- The Truth of the Cessation of Suffering: that suffering indeed can be overcome via the cessation of the root of suffering, the ceasing of all craving or aversion of things that are impermanent that stem from ignorance, representing the ultimate goal of Buddhism.

- The Truth of the Path to the Cessation of Suffering: that there is a specific path which if followed correctly will yield a cessation of suffering. This is the Noble Eightfold Path which consists of right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness and right concentration, the perfection of which yields a perfected state of being, nirvana, the final state of the cessation of suffering.

From the Sutra Pitaka, the “Connected Discourses” we find:

The perceiving of impermanence, bhikkhus [monks], developed and frequently practiced, removes all sensual passion, removes all passion for material existence, removes all passion for becoming, removes all ignorance, removes and abolishes all conceit of “I am.”

Just as in the autumn a farmer, plowing with a large plow, cuts through all the spreading rootlets as he plows; in the same way, bhikkhus, the perceiving of impermanence, developed and frequently practiced, removes all sensual passion… removes and abolishes all conceit of “I am.”[2]

While The Four Noble Truths and Eightfold Noble Path are the cornerstones of Buddhism, the school also lays out a fairly sophisticated causal and psychological metaphysical framework upon which the intellectual foundations of nirvana rest and upon which our ultimate misunderstanding of the nature of existence originates.

A related concept which speaks to the metaphysics underlying Buddhist philosophy is the notion of “dependent origination” or “dependent arising”; Pratityasamutpada in Sanskrit. At the heart of pratityasamutpada are the Twelve Nidanas, the basic psychophysical elements which constitute the set of interdependent and causally related principles from which Samsara, – a Vedic Sanskrit term which is adopted by the Buddhist tradition as well which signifies the repeating cycle of birth and death and is translated as “continuous movement” or “cycle of existence” – emerges. It is the cycle of Samsara, which again is fundamentally characterized by suffering (duhkha), which Buddhism as a theo-philosophical system as a whole is designed to address and it is the notion of Pratityasamutpada which describes in detail the co-conspirators so to speak that underlie this phenomenon.[3]

The Twelve Nidanas are

- ignorance (avidya), which yields

- mental formations and habits (samskara), which yields

- a sense of consciousness or mind (vijnana), which yields

- the world of name and form (namarupa), which in turn yields

- the existence of the sensory apparatus or “sense gates” (sadayatana), which yields

- sensory impressions (sparsa), which yields

- feelings or sensations (vedana), which in turn causes

- cravings and desires (trsna), which yields

- attachment or grasping (upadana), which yields

- formation of new karmic tendencies, or “becoming” (bhava), which in turn yields

- new life or “birth” (jati), which leads to

- aging, decay and death (jaramarana).

Such is how the endless wheel of life is described in Buddhism, which again is fundamentally characterized by suffering and anxiety and via the proper understanding and proper practice (the eightfold noble path) of which can lead to nirvana and the cessation of suffering. It is important to understand that although these twelve “causes” are connected as if in direct cause and effect link, the underlying philosophy links them in a much more holistic and interdependent manner, providing the basis for complex, interdependent life and the source of the belief in the existence of individual consciousness or a sense of “I” or “me”.

In one of his earlier discourses, the Buddha declares that we ought to regard any form of sensation and consciousness, whether “past, future, or present; internal or external; manifest or subtle…as it actually is…: ‘This is not mine. This is not my self. This is not what I am’” (Majjhima Nikāya I, 130).[4]

Buddha also laid out a more psychological and process based view of how this illusory notion of self emerges, consistent with and complementary to the Twelve Nidanas. This is the notion of Skandhas, which is the name given for the five functions or aspects of cognition, the detailed analysis of which yields the unavoidable conclusion that none of them can be said to represent “I” or “self”, another tool used by Buddha to help his students understand the concept of the not-self (anatman), as the association of the individual with one or more of these cognitive faculties so to speak is again the ultimate the source of our ignorance which is the ultimate cause of suffering. These five aspects of cognition, or “aggregates”, are:

- Form or matter: rupa, which represents the physical world as well as our senses which perceive it;

- Sensation or feeling: vedana, the sensory processing aspect of interaction with rupa which is either pleasant, unpleasant or neutral in nature;

- Perception, conception, apperception, cognition: samjna, which is the act of recognition or recognized awareness of an object or idea;

- Mental formations, impulses, volition, desire: samskara, the sum total of all mental habits, conditioned thoughts or ideas, opinions, compulsions or desires which are triggered by the perception of an object and the sensations or feelings associated with said object;

- Consciousness or discernment: vijnana, that which discerns, determines or cognizes, that element of the mind which we associate with consciousness or ego.

The Skandhas are properly understood as interrelated concepts which together constitute the process by which we as rational, sentient beings interact with and experience the world. The five aspects of this process all are strewn together in constant flux, each aspect connected to and in some respects causally related to all of the others. The important deduction from the proper analysis of the framework however is that none of these aspects of “us”, when looked at closely really can be said to represent “I” or “me” in any truly meaningful way, hence the conclusion that this “self” which we so closely identify with is an illusion. This is what has come to be known as the doctrine of “not-self” in Buddhism, anatman in Sanskrit, which sits in direct contrast to the Upanishadic notion of the eternally existent self, or Atman, upon which Vedic philosophy rests.

[1] Pali was mainly a liturgical language from Northern India which was very closely related to Sanskrit with most words existing in both languages with simple phonetic transliterations between the two. It was primarily a liturgical language in the Indo-European/Indo-Iranian language family whose main historical significance is that it is the language of one, if not the, main source of Buddhist scripture and philosophy which is referred to as either the “Pali Canon” or Tipitaka, the latter term meaning “three baskets” in Sanskrit.

[2] Samyutta Nikaya, 22.102. Translation by John D. Ireland 2006. From http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/ireland/wheel107.html#vagga-3.

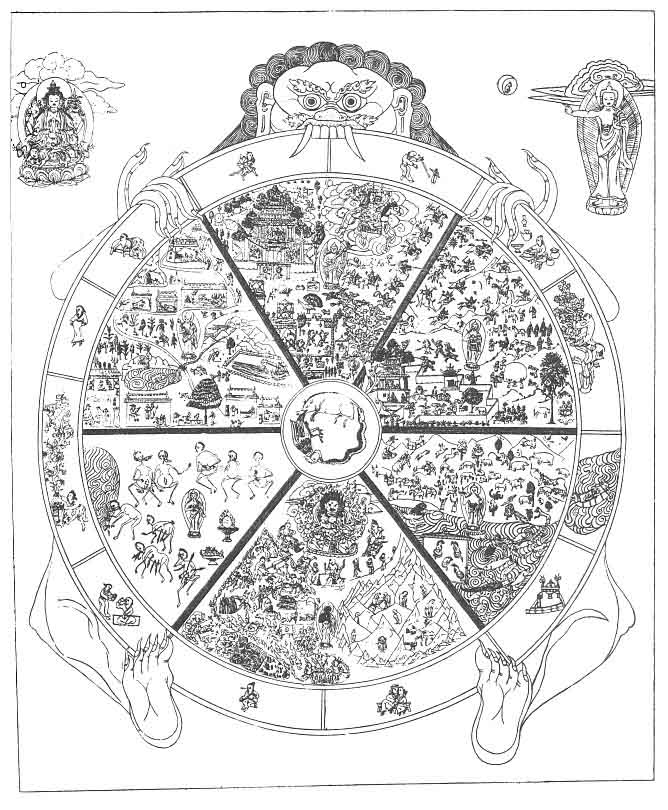

[3] In the Tibetan Buddhist tradition Samsara is depicted by the “wheel of life”, or bhavacakra. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bhavacakra.

[4] Coseru, Christian, “Mind in Indian Buddhist Philosophy”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2012 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2012/entries/mind-indian-buddhism/>. Pg. 4, “The Not-Self Doctrine”

You can definitely see your expertise within the work you write.

The world hopes for even more passionate writers like you who aren’t afraid to say how they believe.

All the time follow your heart.