Egyptian Mythology: The Bedrock of Western Theology

Judaism and Zoroastrianism clearly represented some of the earliest forms of monotheism in the civilized world, and both faiths had their respective prophets which each set of followers believed had had their respective laws, or truths, handed down to them by the one and only God himself – the Yahweh of the Jews and the Ahura Mazda of the Zoroastrians. But both religious systems were also clearly designed, or used, not only as a tool of realization and connection to the divine, but also to unite their people and consolidate power. Underlying the spiritual and religious intent of the two religions/theologies, there was clearly a political motive behind their propagation and proliferation as well, this much seemed pretty evident to Charlie and this characteristic was certainly shared by the monotheistic religions that followed them, most notably Christianity and then Islam.

But where did these monotheistic tendencies or traditions come from? The hunter gatherer societies that preceded the advent of civilization seemed to all be characterized by shaman like priests who professed direct access to and direct realization of the divine, and from these priests or shamans came various ritualistic practices and prayers – the hymnos of the Greeks, yasna of the Zoroastrians and yajna of the Hindus/Indo-Aryans – some of which even survived down to modern times and were captured in the various languages and scriptures of each of these powerful and lasting religious traditions.

So Charlie seemed to be struggling with the fundamental question as to how and why monotheism in its present day form emerged. Was it simply a natural progression, an evolution as it were, of theological systems as civilizations emerged in the Mediterranean and Near/Far East in the second and first millennium BCE? Was it a truly a more advanced form of theology and was the religion of the ancients a pagan system of worship that was to be shunned and abandoned? Furthermore, the question of where these monotheistic traditions came from seemed to be not so straightforward? Was there an element of cultural borrowing at work? Did these traditions emerge from some previously established belief in a single, unified anthropomorphic creative principle from which the cosmos and in turn mankind emerged or did each of them evolve independent of each other? The answers to these questions were crucial to Charlie’s thesis, as the extent of cultural borrowing as it related to the development of theology, religion, in ancient times, had become the essence of his thesis and he needed to explore the concept further to try and establish some semblance of order and progression, if possible, of the emergence of monotheism in the West.

And to shed some light on this evolution of monotheism which was so prevalent and ubiquitous in the modern world, Charlie had to turn back to the earliest known civilization in the ancient world, Ancient Egypt, a civilization where religious beliefs permeated all aspects of life, from which the King himself was looked upon as a manifestation of God on earth and where the journey of the soul in the afterlife, and the notion of last judgment, was the cornerstone of their civilization.

As looked upon the eyes of modern historians, the religious traditions of Ancient Egypt appeared to be bereft of monotheism, in the modern sense of the word. But once which as Charlie dug deeper into the mythology and cosmology of the Ancient Egyptians, there appeared to him to be present some of the basic building blocks of later monotheistic traditions. As Charlie peeled back the façade of Egyptian mythos and their polytheistic tendencies, their obsession with very specific rituals and practices associated with the care of the soul in the afterlife which so notably marked this great civilization, there appeared to be some of the core building blocks of the monotheistic traditions which succeeded them historically. For based upon the archeological and historical evidence, it was quite clear that the civilization and religious beliefs of Ancient Egypt were far older than even the oldest monotheistic traditions such as Judaism and Zoroastrianism, and of course Christianity which was an even later development but emerged from the same region.

Ancient Egypt was a land conquered by many ancient civilizations over the centuries, and yet one with a deep and rich history itself, one steeped in the rule of the Pharaohs in the land of the North African Nile River Delta valley, an area inhabited by mankind since as least as far back as 30,000 to 40,000 years ago, and one which developed a rich and unique mythos and social structure which rested on the firm belief that their leader, their King or Pharaoh, was the human manifestation of the divine on earth, directly connecting the established authority and governance of the people with their worship and belief in god, which for most of Ancient Egyptian history was associated with Atum, or Atum-Ra.

Although various gods and myths were professed and crafted over the millennia in the Egyptian delta region of ancient history, there is one religious development in particular that has drawn much speculation and thought by later scholars, specifically Sigmund Freud, with respect to its relationship to the development of monotheism and its possible connection to Judaism as professed by Moses.

In the 14th century BCE, the King Amenhotep IV attempted to consolidate and synthesize all worship around a single god Aten, subsequently referred to as Atenism, who had historically been a relatively minor entity in the Egyptian pantheon and had been associated with the sun disc of the Egyptian god Ra. Although all kings and pharaohs prior to Amenhotep IV had previously adopted a single deity as their royal patron as it were, there had never been an attempt to establish a single god as the supreme God of the state coupled with the enforcement by law of worship of just one single deity to the exclusion of all others, very much akin to the Jewish tradition where all other gods other than Yahweh were banned from worship as reflected in the ten commandments given to Moses by Yahweh himself on Mount Sinai as the story is told in the Old Testament.

It is this shared concept of exclusive worship bound by law, along with the strong Egyptian influence on Jewish history which is well documented in the Old Testament and the contemporaneous dating give or take a century or two between the life of Moses and the development of Atenism that led Freud to hypothesize that Judaism was simply an offshoot and transfiguration of Egyptian Atenism, morphed and transformed to fit the Jewish people and their history rather than an independent invention as professed by the Torah and Moses[1].

Atenism was surely a unique and distinctive departure from classical Egyptian polytheistic traditions no doubt, and a state authorized and sponsored monotheistic faith did appear on the face of it to share many of the same characteristics of Judaism, and Jewish history clearly was very tied to Egypt, but the direct association of Moses with Atenism seemed to be a stretch to Charlie, although perhaps both movements (if you could call them that) did originate from a single underlying monotheistic tendency, one which forked off the Jews as a separate people as they migrated out of Egypt and one which was ultimately rejected by the Egyptian people whose polytheistic tendencies were clearly just too deeply rooted to be carved out by law, no matter what divine authority it came from.

But to understand what this Atenism truly was, and how it fit into this melting pot of the rampant polytheistic forces that so marked ancient Egypt, and to understand why it was ultimately rejected by the Egyptian people, Charlie needed to get a better grasp on the socio-political, and ultimately theological and mystical, context within which it emerged. And with Ancient Egypt especially, given its long history in the Nile River delta coupled with its deeply rooted religious socio-political system, a society which worshipped the King as a manifestation of God himself and the priesthood was extremely powerful and embedded in every part of society, one must have a bit of background on Egyptian history, some of the characters and narratives of Egyptian mythology, and of course as much of an understanding of the cosmological beliefs of this ancient people as possible, beliefs which as with all ancient civilizations underpinned their entire world view and social structure.

Before Ancient Egypt was conquered and ruled by foreigners starting with the Persians in the middle of the first millennium BCE, then followed by the Greeks under Alexander the Great in 332 BCE, then the Romans in 30 BCE for some 5 or 6 centuries and then the Muslims/Arabs for some thousand years plus thereafter, it was one of the most sophisticated and first of all ancient civilizations, with a system of writing and architecture that dates back to the 4th millennia BCE, making it one of, if not the, oldest civilization of mankind. The beginning of Ancient Egyptian civilization is typically marked by the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt by its first pharaoh[2] in the latter part of the 4th millennia BCE, what modern historians have come to call the Predynastic Era which succeeded the Neolithic period in the Egyptian delta.

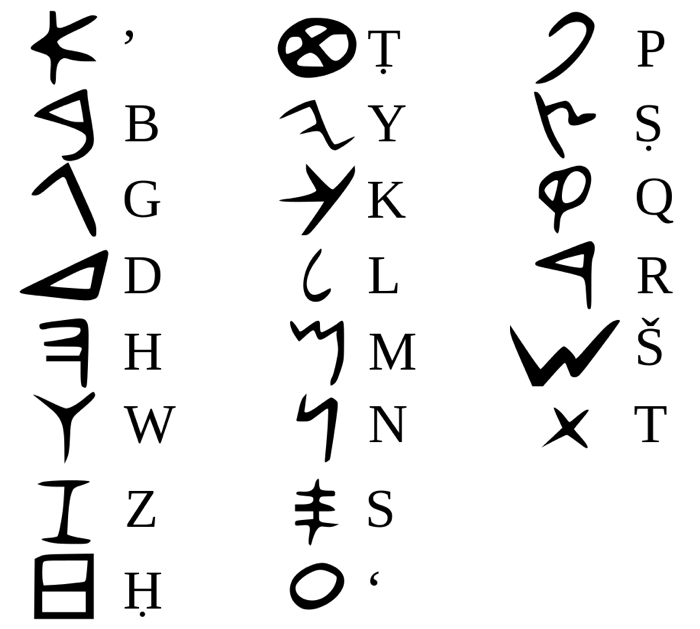

This period of unification of Upper and Lower Egypt is also the time period associated with the emergence of Egyptian forms of writing as well, at first with hieroglyphs which we find inscribed on the tombs of pharaohs from this period, and later in the tombs of the upper and middle class as hieroglyphic inscriptions became more common and the hieroglyphics evolved to include not only ideograms and logographic (picture) elements, but also alphabetic elements to capture specific pronunciations and annunciations of spells designed to capture the specific annunciations and words used by the Egyptian priesthood for specific ceremonies and rituals, most notably of course the burial of the dead.

Alongside the development of hieroglyphs which evolved for some two millennia (and was still used up until the 3rd and 4th centuries CE after Egypt came under first Greek then Roman rule), a sister script called hieratic[3] also emerged which although closely related to hieroglyphics was character and phonetic/alphabet based. Hieratic was easier to write than hieroglyphs and like its sister hieroglyphs, was initially only used by priests and scribes to transliterate specific rituals and spells. Eventually, in the middle and latter part of the first millennium BCE, hieratic evolved into a Demotic, a script designed for more secular use that in most instance was used to capture the language of the period of the same name, i.e. Demotic, which succeeded Middle and Late Egyptian which had been the language spoken by Egyptians for the preceding few millennia in some form or another.

The Egyptian Demotic language (not to be confused with the modern Greek language with the same name, i.e. demotic which is typically written with a lower case “d”) and the script that supported it that is referred to with the same name, i.e. Demotic, was prevalent in the middle and late first millennium BCE and was used for almost a thousand years up until the 5th century CE or so[4]. Both hieroglyphics and hieratic script are used throughout Ancient Egypt from the Predynastic Period (c 3100 BCE) all the way through the 6th century CE or so and it is through these writing systems, and the languages transcribed therein, that we can get a glimpse of the theology and religion of Ancient Egypt[5].

Our current historical view of categorizing Ancient Egyptian history into dynasties, typically marked by roman numerals, is derived from the first Egyptian historian Manetho, a 3rd century BCE priest and historian from Egypt who authored a three volume treatise of the history of Egypt entitled Aegyptiaca, or “History of Egypt”, a period of Egyptian history when it was under Greek, or Hellenic influence hence the use of Greek to author his work. Manetho, according to later historians and excerpts of his work that do survive, gave a detailed and Egyptian perspective on the history of Egypt, beginning with the period of Egyptian societal consolidation under the rule of a single unified King or Pharaoh which he calls Menes circa 3100 BCE. His work is presumed to have been motivated by providing an Egyptian perspective on the history of Egypt in contrast to the one provided by Herodotus several centuries prior, whose perspective was not only foreign but also lacking with respect to a proper chronology and depth of coverage.

Later, more modern Egyptian historians (aka Egyptologists) break down the periods of Ancient Egyptian civilization into different successive periods, each earmarked by the transition from one dynasty to another, where a dynasty doesn’t necessarily represent a blood lineage from one ruler to the next but some cultural or societal break in Egyptian history that denotes the transition into different period. All Ancient Egyptian texts and inscriptions fall into one or more different periods, and Egyptologists typically use the dynastic classification to denote the period within which a particular text, form of writing, or inscription is found so in order to have proper context of the time period and socio-political context of a given theological text or inscription, it was important to be able to classify it in the appropriate dynasty and/or period. The list below summarizes the periods briefly, covering some 4 thousand years from circa 3100 BCE up into modern times where Egypt came under Islamic influence[6].

- Early Dynastic Period (c. 3100-2686 BCE). Dynastic period begins with the first King or Pharaoh Menes (aka Narmer). Covers Dynasties I and II.

- Old Kingdom Egypt (c. 2686-2181 BCE). III-VI dynasties. Capital in Memphis.

- 1st Intermediate Period (c. 2181-2055 BCE). VII-XI dynasties. Marked by conflict between Thebes in South and Heracleopolis in North.

- Middle Kingdom Egypt (c. 2055-1650 BCE). XI-XIV dynasties. Period of (re)Unification. Osiris becomes ever more important as a deity. Capital in Thebes in XI dynasty and then and el-Lisht from XII to XIV. First versions of Book of the Dead date from this period.

- 2nd Intermediate Period (c. 1650-1550 BCE). XV-XVII dynasties. Marked by foreign rule, or rule by “Hyksos”, or “heqa khaseshet” in Egyptian which is roughly translated as “ruler(s) of the foreign countries”[7].

- New Kingdom Egypt (c. 1549-1077 BCE). XVIII to XX dynasties. Also referred to as Egyptian Empire Period where Egypt attained its greatest territorial extent to the south into Nubia and North into Near/Middle East. Amenhotep IV (c. 1352-1335 BCE), with whom Atenism is associated is a King from the XVIIIth dynasty, roughly from the middle of this period.

- 3rd Intermediate Period (c. 1069-653 BCE). XXI-XXV dynasties. Marked by political instability and fractured rule.

- Late Period Egypt (c. 664-332 BCE). XXVI-XXXI dynasties. Last period of Egyptian independence until Persian conquest – 1st Achaemenid Period 525-404 BCE and 2nd Achaemenid Period 343-332 BCE – until conquest by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE after which Egypt falls under strong Hellenic influence.

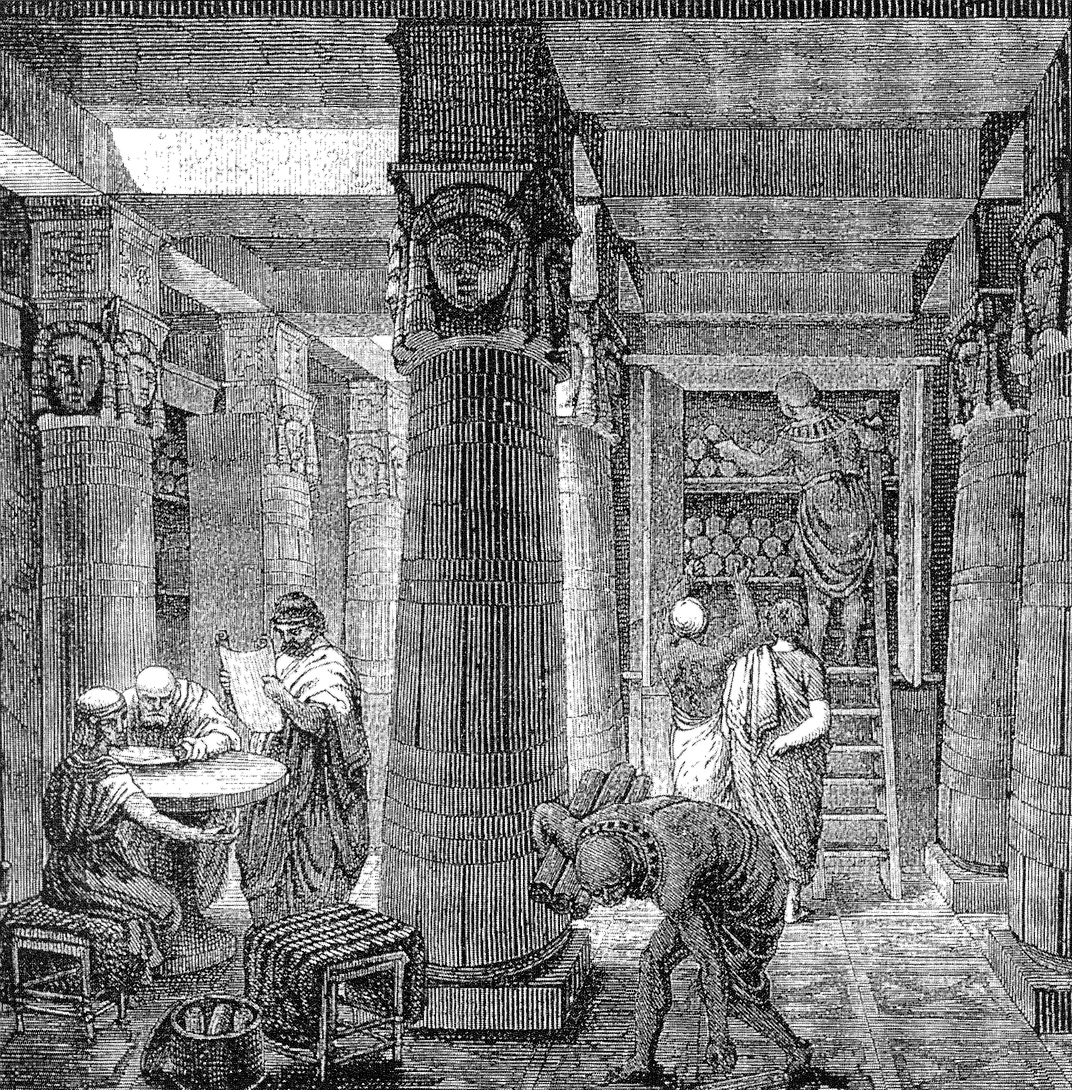

- Ptolemaic Period (c. 332-30 BCE). Dynasty of Hellenic descended pharaohs begins, Alexandria is established as the capital and becomes the intellectual epicenter of the ancient world with the creation of the Library of Alexandria under Ptolemy I. Period lasts until Roman conquest in 30 BCE.

- Roman & Byzantine Egypt (c. 30 BCE-641 CE). Egypt falls under Roman and subsequent Byzantine rule and influence.

- Egypt under Islamic Influence (639 CE-18th century). Islamic invasion and conquering of Egypt during the Muslim conquests in 639 CE. Egypt falls under Islamic influence for over a thousand years until modern times.

The dynastic period of Egypt lasting some three thousand years or so reaching far back in antiquity is characterized not only by a rich and unique pantheon of gods and their associated mythology (and ritual) that not only emphasized the belief in their ruler as a manifestation of god on earth whose authority derived from divine provenance, but also by a marked with what can only be call an obsession with the transmigration of the soul and the belief in an afterlife, emphasis that perhaps derives from the context within which almost all of this material and inscriptions survive down to us, namely first through Pyramid and Coffin (sarcophagus) inscriptions in the 3rd and 2nd millennium BCE, and then later on papyrus documents as the literature become more widespread and prevalent in society, and more standardized as what is known today as the Egyptian Book of the Dead.

This extant material, inscriptions in hieroglyphics within pyramids, tombs and on sarcophagus and then later in hieratic and hieroglyphic script on papyrus, indirectly refers to and incorporates their cultural and spiritual belief system and worldview, corresponding to what today we would call religion. All of this material was in fact crafted and designed specifically to protect, guide, and preserve the bodies and souls of the Egyptians into their journey into the afterlife, perhaps better translated as the netherworld, giving rise to their practices of mummification and pyramid and tomb building which were attempts to preserve the body, and its soul, for its journey beyond life into the afterworld.

The incantations/spells/utterances which we find as part of this literature were designed for this purpose were initially reserved only for the Kings and Pharaohs in the early dynastic period and Old Kingdom, what has become to be known as the Pyramid Texts, and then later adopted by the Egyptian aristocracy as well during the First Intermediate Period and Middle Kingdom, known as the Coffin Texts, and then finally in its most mature and standardized form which was adopted more broadly by the general population in the New Kingdom dynasties through the Ptolemaic Period as the Egyptian Book of Dead which existed in a variety of renditions and began to be written down on papyrus scrolls and buried along with the dead[8].

Egyptian mythology is undoubtedly best known for this association, perhaps more aptly described as an obsession, upon the burial and rituals associated with death and the extensive steps taken to prepare the soul (most commonly associated with the Egyptian term Ba) for its journey into the afterlife, and it is from this context surrounding death and the afterlife for the most part from which we gain insight into Ancient Egyptian religious beliefs. Therefore Ancient Egyptian religion is closely associated with these sophisticated and wide ranging spells and incantations and their associated mythology surrounding death and the journey of the soul in the afterlife.

The Egyptian notion of Ba was somewhat different than our conception of the soul, perceived to be the aspect of the individual in toto which was permanent and persisted beyond death, perhaps best described as the fundamental essence of the individual which was deathless and timeless. Ba was also used in reference to inanimate objects as well, denoting the more broad meaning of the word in Egyptian to describe the essential nature of a thing, either animate or inanimate, with perhaps a close correspondence to Aristotle’s notion of being qua being, or that which characterizes the primary essence of a thing and defines its existence, which he outlines in his Metaphysics.

Furthermore, as reflected in the Book of the Dead which represents the most mature form of the Egyptian religion/theology as it stands from the latest part of Egyptian antiquity, special importance was given to not only the individual’s name which was given to them at birth, ren or rn, which the Egyptians held supported the continued existence of the soul as long as it was kept alive and spoken, but also special significance was given to the heart, ib or jb, which was looked upon as the seat of all human emotion, feeling, thought, will and intention and was used in the Egyptian Weighing of the Heart ceremony where the individual’s heart was weighed/balanced against the feather of Maat which represented truth, justice, or order; the outcome of such balance determining the ultimate fate of the individual. It was interesting to note that this ceremony as depicted in the Coffin texts and then later encapsulated in the Book of the Dead most certainly has parallels to the Christian moral framework based upon the notion of last judgment.

Clearly Ancient Egyptian religion, as reflected first in the Pyramid Texts from the Old Kingdom, the Coffin Texts from the Middle Kingdom, and then further structured and canonized in the Book of the Dead in its various forms which persisted into the latter part of the first millennium BCE and into the Common Era (CE) even after Egypt came under foreign rule by the Persians, Greeks and then Romans, their relationship and perception of the divine was complex and multifaceted and characterized by the worship of many different deities in a variety of forms, each reflecting some aspect of nature and/or some anthropomophocized (or pseudo-anthropomophocized as the case may be) aspect of God, consistent in fact with almost all of the middle and late Bronze age contemporaneous cultures and civilizations in the Mediterranean region and even into the Near and Far East.

But to what extent was Egyptian cosmology or theology adopted by its sister cultures and peoples to the North and East? Interestingly, Herodotus in fact actually points to a very direct relationship, and ultimate source, of at least some of the Greek pantheon directly from Egypt. From his Histories from Volume I Book II, verses 50-53, we have:

50. Moreover the naming of almost all the gods has come to Hellas from Egypt: for that it has come from the Barbarians I find by inquiry is true, and I am of opinion that most probably it has come from Egypt, because, except in the case of Poseidon and the Dioscuroi (in accordance with that which I have said before), and also of Hera and Hestia and Themis and the Charites and Nereïds, the Egyptians have had the names of all the other gods in their country for all time. What I say here is that which the Egyptians think themselves: but as for the gods whose names they profess that they do not know, these I think received their naming from the Pelasgians, except Poseidon; but about this god the Hellenes learnt from the Libyans, for no people except the Libyans have had the name of Poseidon from the first and have paid honour to this god always. Nor, it may be added, have the Egyptians any custom of worshipping heroes. 51. These observances then, and others besides these which I shall mention, the Hellenes have adopted from the Egyptians; but to make, as they do, the images of Hermes with the /phallos/ they have learnt not from the Egyptians but from the Pelasgians, the custom having been received by the Athenians first of all the Hellenes and from these by the rest; for just at the time when the Athenians were beginning to rank among the Hellenes, the Pelasgians became dwellers with them in their land, and from this very cause it was that they began to be counted as Hellenes. Whosoever has been initiated in the mysteries of the Cabeiroi, which the Samothrakians perform having received them from the Pelasgians, that man knows the meaning of my speech; for these very Pelasgians who became dwellers with the Athenians used to dwell before that time in Samothrake, and from them the Samothrakians received their mysteries. So then the Athenians were the first of the Hellenes who made the images of Hermes with the /phallos/, having learnt from the Pelasgians; and the Pelasgians told a sacred story about it, which is set forth in the mysteries in Samothrake. 52. Now the Pelasgians formerly were wont to make all their sacrifices calling upon the gods in prayer, as I know from that which I heard at Dodona, but they gave no title or name to any of them, for they had not yet heard any, but they called them gods ({theous}) from some such notion as this, that they had set ({thentes}) in order all things and so had the distribution of everything. Afterwards, when much time had elapsed, they learnt from Egypt the names of the gods, all except Dionysos, for his name they learnt long afterwards; and after a time the Pelasgians consulted the Oracle at Dodona about the names, for this prophetic seat is accounted to be the most ancient of the Oracles which are among the Hellenes, and at that time it was the only one. So when the Pelasgians asked the Oracle at Dodona whether they should adopt the names which had come from the Barbarians, the Oracle in reply bade them make use of the names. From this time they sacrificed using the names of the gods, and from the Pelasgians the Hellenes afterwards received them: 53, but whence the several gods had their birth, or whether they all were from the beginning, and of what form they are, they did not learn till yesterday, as it were, or the day before: for Hesiod and Homer I suppose were four hundred years before my time and not more, and these are they who made a theogony for the Hellenes and gave the titles to the gods and distributed to them honours and arts, and set forth their forms: but the poets who are said to have been before these men were really in my opinion after them. Of these things the first are said by the priestesses of Dodona, and the latter things, those namely which have regard to Hesiod and Homer, by myself.[9]

From Herodotus’s perspective then, there was clearly some cultural borrowing that had taken place between the Greek and Egyptian cultures, one that clearly grew more integrated and synthesized as time passed and the Greek and Egyptian (and Later Roman and Byzantine) cultures became more closely tied and interwoven. Over the centuries, particularly in the last half of the first millennium BCE into the Common Era when Egypt came under Greek and then Roman rule, its mythos and pantheon become merged and synthesized with their Greek and Roman counterparts, perhaps best exemplified in the Greco-Egyptian god who came to be known in the Roman era and into the Middle Ages as Hermes Trismegistus, a pseudo-mythical figure to whom the Hermetic doctrine was attributed who represented a synthesis and consolidation of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth.

The Corpus Hermeticum, which represents the core of the Hermetic doctrine, became a fairly widespread and popular philosophical system throughout the Mediterranean in first millennium CE, in many respects akin to Gnosticism which emerged in the Mediterranean at around the same time. Hermes Trismegistus, or Hermes Thrice Great, was so called because he was said to have mastered the three great pillars of ancient wisdom or knowledge; namely astrology, alchemy and theology or as stated in the Poimandres, one of the initial chapters in the Corpus Hermeticum, Hermes was the greatest philosopher, the greatest king and the greatest priest.

The complete doctrine surrounding Hermeticism, originally written in Greek somewhere between the third and fifth centuries CE and then later translated into Latin in the 15th century, includes not only the Corpus Hermeticum but also The Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus and The Perfect Sermon or the Asclepius. The doctrine reflects many Greek philosophical, Neo-Platonist, Gnostic and even Christian influence reflecting the prevailing pseudo-mystical, religious and theo-philosophical traditions that were emerging at that time in history in the Mediterranean a few centuries after the death of Christ as Christianity was in its infancy and before Christianity took full root in the Mediterranean in the latter part of the first millennium CE.

Hermetic doctrine as outlined in the Corpus Hermeticum speaks to the mystical and philosophical secrets of mankind that are taught to Hermes himself by a mythical figure named Poimandres who is identified with God, the form of the work in many respects resembling Platonic dialogues, where teachings and discourse, a form of dialectic, are used to convey meaning to the reader rather than a revealed scripture of sorts reflecting the Neo-Platonic influences on the tradition. The treatise also includes a pseudo Gnostic cosmology which describes the establishment of the world order via Logos and Nous, Reason and Intellect respectively, displaying not only Gnostic characteristics, a contemporary philosophical movement that was one of the early competitors to Christianity, but also clear traces of of the philosophy of Anaxagoras, which are also seen in the Derveni papyrus, with its prominence of the role of Nous in the underlying structure and shape of the cosmos. Speaking to its precursors to chemistry and science, Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine and healing from which our modern image of two serpents encompassing a staff comes from, plays a prominent role in the Corpus as a disciple of Hermes to whom the teaching is originally passed down to.[10]

From the early dynastic period of Egypt as reflected in the Pyramid and Coffin Texts, and then later in the New Kingdom as reflected in Book of the Dead, we see a prominence of the notion of the importance of the protection and preservation of the established order of the universe, or Maat, that existed in eternal conflict with evil, or darkness, typically drawn as a serpent or snake in the earliest texts, and then later coming to be referred to as ı͗zft, or Isfet, which meant “injustice”, “chaos”, “violence” or was even sometimes used as a verb meaning “to do evil”.

By the VIIIth dynasty onward, this serpent which represented the forces of darkness and evil became personified as the god Apep, and his battle with the forces of good played which played such a prominent role in New Kingdom Egyptian mythology as reflected in the epic battle between Apep and the sun god Ra, who represented the forces of light and good, which were believed to struggle each night as the Sun passed down through the horizon into the underworld, the place where Apep lie in waiting. In this context Apep, who eventually was replaced by Set in later Egyptian mythological tradition, came to represent the god of the underworld, or the Hades of the Greek tradition.

We see even in a Coffin Text inscription[11] specific reference to the requirement of the dead being cleansed of Isfet in order to be reborn in the netherworld, or Duat, speaking to the fundamental and very old Ancient Egyptian notion of the universe being a battleground of the forces of good and evil, light and darkness, both at the cosmic level and at the spiritual or individual level. These very same themes can also be found in the Zoroastrian tradition of the Indo-Iranian/Persian peoples to the East where Ahura Mazda and his band of angels are in constant struggle with Angra Mainyu and his band of demons (devas) who represent falsehood, darkness and evil, as well as of course in the Christian tradition, where God and his counterpart the fallen angel Satan are also portrayed as opposing and dueling forces of the world. Another interesting Christian parallel to the Egyptian Isfet can be found in the Judeo-Christian Garden of Eden story where it is the serpent who tricks Adam and Eve into eating from the Tree of Life, plunging mankind out of the Garden and into the mortal world of endless toil, death and suffering.

But despite the different creation myth variants and different versions of the Egyptian pantheon that can be found throughout dynastic Egypt as the capital shifted between Memphis, Thebes, Heliopolis, and then later in Hellenic Alexandria, there was always present this firm belief in the in the importance of order. Maat, in the world, and its epic struggle with chaos and evil, Isfet or Apep, that defined the universe as well as the internal world of the spirit. We see these same themes and notion of eternal struggle not only with Zoroastrianism and Christianity, but also with the Greeks as well, reflected in the epic battle between Zeus and the Titans in the Theogony, whereafter the Titans were forever bound and chained within Tartarus, the realm of the dead overseen by the Greek god of the underworld Hades, corresponding almost precisely to the Egyptian netherworld Duat and its presider Apep.

And amongst the foremost Cottus and Briareos and Gyes insatiate for war raised fierce fighting: three hundred rocks, one upon another, they launched from their strong hands and overshadowed the Titans with their missiles, and buried them beneath the wide-pathed earth, and bound them in bitter chains when they had conquered them by their strength for all their great spirit, as far beneath the earth to Tartarus. For a brazen anvil falling down from heaven nine nights and days would reach the earth upon the tenth: and again, a brazen anvil falling from earth nine nights and days would reach Tartarus upon the tenth. Round it runs a fence of bronze, and night spreads in triple line all about it like a neck-circlet, while above grow the roots of the earth and unfruitful sea. There by the counsel of Zeus who drives the clouds the Titan gods are hidden under misty gloom, in a dank place where are the ends of the huge earth. And they may not go out; for Poseidon fixed gates of bronze upon it, and a wall runs all round it on every side. There Gyes and Cottus and great-souled Obriareus live, trusty warders of Zeus who holds the aegis.[12]

So at this point Charlie was starting to see many of these Ancient Egyptian mythological themes, deities and underlying cosmic principles in many, if not all, of the civilizations of its neighbors with which they clearly had some form of contact, either via trade and travel or in later times through war, and subjugation. We also see explicit reference to the borrowing and renaming of Egyptian gods by the Greeks from Herodotus, a fairly objective and reliable source of Ancient History for the Greeks, Persians and Egyptians in the Mediterranean from the middle of the 5th century BCE.

Furthermore, Charlie also saw a clear Egyptian influence on later, mostly Hellenic/Greek, theo-philosophical traditions which emerged in the Mediterranean during the time of Hellenic and then later Roman/Latin influence in Egypt as evidenced by the clear Greco-Egyptian tradition associated with Hermes Trismegistus which had Greek philosophical undertones throughout and yet at the same time was associated with the Egyptian god of wisdom, learning and knowledge Thoth. We even have perhaps the most widely used and prominent translation of the Hebrew Old Testament, i.e. the Septuagint, commissioned and taking place in Egypt during the Ptolemaic Period in Alexandria, the city founded by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE after he conquered Egypt which subsequently became the intellectual capital of the ancient Mediterranean for some four or five centuries, pointing quite directly in fact to Egyptian influence on the Judeo-Christian tradition that was to dominate the religious landscape of the Western world for some two thousand years.

But Charlie remained curious as to how strong these monotheistic tendencies were within Egypt, forces that no doubt had some level of influence on the monotheism movement started by Amenhotep IV in the XVIIIth dynasty (circa 1340 BCE), Atenism, as short lived as it was, and forces that undoubtedly at some level shaped the formation of the religion of the Jews via from Moses who if he lived, lived no more than one or two centuries removed from Amenhotep IV’s rule over Egypt and who clearly had strong ties to Egypt as so well documented in the Old Testament.

Was there a thread of monotheistic thought and belief that evolved from and within Ancient Egypt that spread to the East or was Atenism simply a fluke espoused by a deranged King that was fundamentally rejected by an uncivilized, pagan and primitive populace? Was monotheism as reflected in the Judeo-Christian (and Zoroastrian) traditions borrowed from the Egyptians, as Freud would have us believe, or was it an independent invention given to Moses by God himself on Mont Sinai as the Jews, and Christians, have been teaching us for some 2500 years?

Although the connection could not be directly established, Charlie did see a lot of evidence for the origin of much of Western and Near Eastern civilization mythos, and to a lesser extent perhaps Hellenic philosophy and Judeo-Christian theology, from Ancient Egypt given that their mythological tradition could be traced much deeper into antiquity (as seen in the Old Kingdom Pyramid Texts from circa 2500 BCE and then the Coffin texts from a few centuries later) and given the evidence of social and cultural contact and exchange that clearly took place between the Egyptian and their direct neighbors to the North and East, namely the Canaanite/Semitic people, the Greeks, and even the Persians, from the second millennium BCE onwards.

What was clear however, was that something very interesting and unique in Egyptian socio-political and religious history occurred under the reign of the XVIIIth dynasty King Amenhotep IV, who ruled sometime during the second half o the 14th century BCE (~1350-1330 BCE). And although its influence and prominence lasted but a decade or two, it did represent one of the earliest documented forms of monotheism in the ancient world and one that shared the fundamental and distinct characteristic of modern day monotheism as prescribed by Moses and the Jews which forbid the worship of all other gods except the one true God – which in this case was Aten, a mythical figure that was associated with the Egyptian sun god Ra.

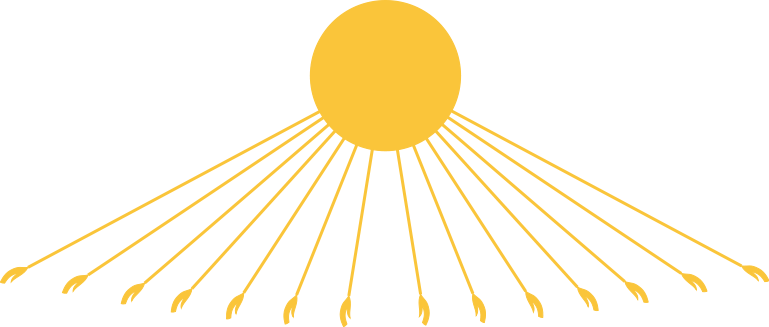

Ra, or Re, had always held great significance and relevance to the Ancient Egyptians, he was one of the principal gods in the Egyptian pantheon even from early Old Kingdom Egypt (he is prominently portrayed in the Pyramid Texts for example) and represented the force of light and good in the world and was the protector of Maat, or the world order. Prior to the reign of Amenhotep IV, the sun god was worshipped as in the temple of Heliopolis, an ancient Egyptian city dating back to Old Kingdom Egypt which was, according to Herodotus, an intellectual and historical center of Ancient Egypt as well. In later Egyptian history, as it entered into the Middle and New Kingdom, Ra also became also associated with Amun as Amun-Ra, and Atum as Atum-Ra in various competing pantheons from the different centers of worship in Ancient Egypt.[13] Ra however, sometimes written as Re, in all the traditions was looked upon as one of the most revered and most powerful gods of the entire Egyptian pantheon, whose daily struggle against the forces of darkness as he set on the horizon each day was one of the most prevalent and powerful mythological themes of the ancient Egyptian people. Aten, which historically was associated with the disc of the sun itself, had not been much of a player in Egyptian mythos up until Amenhotep IV’s rule, certainly nowhere near as prominent as Ra himself.

But in the early part of Amenhotep IV’s reign, for reasons that can be looked upon as socio-political, i.e. as a means to perhaps consolidate his power, Amenhotep IV established what has come to be known as Atenism as the official religion of the state, and proclaimed that Aten be worshipped to the exclusion of all other gods, not only outlawing the worship of all other gods even in individual homes, but also even going so far as to oversee the systemic destruction of idols and all other references to other gods in the Egyptian pantheon throughout the land, gods and goddesses that had been worshipped for millennia, making it one of the earliest forms of monotheism in all of mankind’s history.

This development marked a significant divergence from standard Egyptian policy and practices that preceded it which had, like almost all ancient civilizations in antiquity to some degree or another, accepted the various gods and goddesses of the Egyptian pantheon permitted religious freedom of worship throughout the kingdom, as long as of course the King himself was looked upon as the penultimate manifestation of the divine on earth. Amenhotep IV not only forbade the worship of all other deities other than Aten, he changed his name to Akhenaten, or “one agreeable to Aten”, and constructed a new capital city called Akhetaten in the deities’ honor, modern Amarna.

An excerpt from a hymn to Aten found in identical form in five ancient Egyptian tombs illustrates at least some of the basic monotheistic conception of Aten that was proselytized by Amenhotep IV, mainly associating Aten with the characteristics historically associated with Ra but somewhat unique nonetheless in the forced worship of Aten and the exclusion of other forms of worship.

Splendid you rise, O living Aten, eternal lord!

You are radiant, beauteous, mighty,

Your love is great, immense.

Your rays light up all faces,

Your bright hue gives life to hearts,

When you fill the Two Lands with your love.

August God who fashioned himself,

Who made every land, created what is in it,

All peoples, herds, and flocks,

All trees that grow from soil;

They live when you dawn for them,

You are mother and father of all that you made.[14]

Unique to Atenism relative to the other ancient monotheistic faiths is of course is it’s socio-political features, i.e. there is no revealer of truth or scripture to which it adheres as is the case with other monotheistic traditions that emerged from ancient Western civilization, outside of Amenhotep IV himself. Atenism is simply the decree of truth from the ruler of the day in what can perhaps best be looked at as an attempt at the consolidation of power by Amenhotep IV, a decree which was subsequently overturned, and the destruction of all temples of Aten ordered, under the ruler Horemheb who followed Amenhotep IV to power. But there are uniquely monotheistic traits to Atenism as it was professed and doled out to the Egyptian people, and to this extent it is worth consideration and study within the context of the development of monotheism historically, and of course as pointed out by Freud, its relationship with to Judaism, although it cannot be directly established, Charlie could not completely ignore either.[15]

Although the Egyptian cosmology of the various temple cults and traditions that existed in Ancient Egypt can be inferred and deduced from the Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts, and even from the much later more canonized Book of the Dead, the first, and only in fact, real coherent cosmological tradition of Ancient Egypt can be found, exist in two similar variants from a single papyrus found in Luxor (ancient Thebes) in a papyrus authored or commissioned by a priest named Nes-Menu or Nes-Amsu, written in Late Egyptian in hieratic script. The papyrus dates to the Ptolemaic Period, as it refers directly to Alexander the Great, and deals specifically with spells and incantations that are designed to guard against the evil god Apep, its insertion into the papyrus implying perhaps to the secret potency and mystical powers that were believed to be contained within the creation story/cosmology as well its relevance to the ultimate protection against the forces of darkness and evil.

The initial narrative, which is somewhat shorter than the second one, is included in full below and one of the most marked characteristics here to Charlie at least was that there was in fact a single creative principle that was called out from within which the universe emanates, a god called Neb-er-tcher, according to Wallis Budge one of the most preeminent Egyptologists of the modern era, becomes associated with the Judeo-Christian God in Coptic literature from later Roman/Latin times.[16]

[These are] the words which the god Neb-er-tcher spoke after he had come into being: “I am he who came into being in the form of the god Khepera, and I am the creator of that which came into being, that is to say, I am the creator of everything which came into being. Now the things which I created, and which came forth out of my mouth after that I had come into being myself were exceedingly many. The sky (or heaven) had not come into being, the earth did not (exist, and the children of the earth, and the creeping things had not been made at that time. I myself raised them up from out of Nu, from a state of helpless inertness. I found no place whereon I could stand. I worked a charm upon my own heart (or, will). I laid the foundation [of things] by Maat, and I made everything which had form. I was [then] one by myself, for I had not emitted from myself the god Shu, and I had not spit out from myself the goddess Tefnut; and there existed no other who could work with me. I laid the foundations [of things] in my own heart, and there came into being multitudes of created things, which came into being from the created things which were born from the created things which arose from what they brought forth. I had union with my closed hand, and I embraced my shadow as a wife, and I poured seed into my own mouth, and I sent forth from myself issue in the form of the gods Shu and Tefnut. Said my father Nu: ‘My Eye was covered up behind them (i.e., Shu. and Tefnut), but after two hen periods had passed from the time when they departed from me, from being one god I became three gods, and I came into being in the earth.’ Then Shu and Tefnut rejoiced from out of the inert watery mass wherein they and I were, and they brought to me my Eye (i.e., the Sun). Now after these things I gathered together my members, and I wept over them, and men and women sprang into being from the tears which came forth from my Eye. And when my Eye came to me, and found that I had made another [Eye] in place where it was (i.e., the Moon), it was wroth with (or, raged at) me, whereupon I endowed it (i.e., the (second Eye) with [some of] the splendour which I had made for the first [Eye], and I made it to occupy its place in my Face, and henceforth it ruled throughout all this earth. When there fell on them their moment through plant-like clouds, I restored what had been taken away from them, and I appeared from out of the plant-like clouds. I created creeping things of every kind, and everything which came into being from them. Shu and Tefnut brought forth [Seb and] Nut; and Seb and Nut brought forth Osiris, and Heru-khent-an-maati, and Set, and Isis, and Nephthys at one birth, one after the other, and they produced their multitudinous offspring in this earth.”[17]

Here we find then, in the latter part of the first millennium BCE after Egypt had come under direct Greek influence, not only a more structured and standardized creation myth, but also the insertion, or at least explicit documentation, of a single, creative divine pseudo-anthropomorphic principle, a cosmology that in many respects was similar to its counterpart in Greece as reflected in Hesiod’s Theogony or in Orphism, albeit in a different style of prose, with a different pantheon of gods, and a different cultural context.

The cosmology outlined in the papyrus of Nes-Manu however, with the carving out of a single divine creative principle from which the universe, the gods of the Egyptian pantheon, and then ultimately mankind, emerges does represent the early stages of monotheistic theology in some respects, although perhaps in a less evolved form and of course absent of the legal mandate of a single form of worship that was such a prominent characteristic of Judaism and then later Christianity. Atenism however, as failed as it was due undoubtedly to the resistance it met by the people and priests who did not ascribe to Aten as the one and only true God, did in fact display these same restrictive, and politically motivated tendencies. Whether or not the Jews (Moses) and the Christianity as it was adopted by the Romans borrowed Amenhotep IV’s methodology remained an open question of course.

What Charlie could surmise however, and what did seem clear, was that in Ancient Egypt, similar to the ancient Sumer-Babylonian, Persian, and Greece civilizations, there existed an implied and esoteric and mystical monotheistic tendency that was reflected in their respective cosmological narratives, while at the same time there was an accepted localization of beliefs that allowed for the worship of specific deities with specific modes of worship in each town or city, as long as they adhered to a basic pantheonic structure which was characteristic of the civilization as a whole.

This structure of religious authority which allowed for independence at the city or town level, while still adhering to what could be called state sponsored religious practices that were mandated or practiced by the governing authority, the King in the case of ancient Egypt, is in many respects similar to how the United States is set up, with some powers given to the States to mandate and enforce, whilst other powers – like the power to hold an army and defend the nation – is mandated and enforced at the federal level. Our model is wholly secular of course but the analogy seemed pretty clear to Charlie at least.

[1] Freud’s Moses and Monotheism originally published in 1937 in German and subsequently published in English in 1937. In it, Freud hypothesizes that Moses was not a Hebrew or of Semitic descent, but was in fact an Egyptian nobleman and perhaps even a follower of Atenism.

[2] Menes, aka Narmer is the first pharaoh said to have united Upper and Lower Egypt. It is notable that the Ancient Egyptians did not use the term pharaoh; this word is taken from the Old Testament context and then later applied to Ancient Egyptian history. King is a more appropriate term but we will use King or Pharaoh interchangeably throughout. For more information on the etymology and history of the term pharaoh see http://ashraf62.wordpress.com/ancient-egypt-knew-no-pharaohs/.

[3] The word “hieratic” was first used by the Christian theologian Saint Clement of Alexandria who lived and wrote in in the late 1st and early 2nd century CE and is derived from the Greek word hieratika which literally means “priestly writing”.

[4] Demotic, the language, was succeeded by Coptic, which was the most common Egyptian language spoken up until the 17th century CE.

[5] Demotic was succeeded by the Coptic writing system/alphabet (and the Coptic language which it is designed to render) which started to take root in the 3rd century CE and is still in use in some Egyptian churches and other places today. The Coptic alphabet is based upon the Greek alphabet with strong Demotic influence.

[6] The primary source for the Dynasty, Kingdom and Period list included here is from the History of Egypt section of Wikipedia. For more detail see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egypt.

[7] Hyksos were a Canaanite/Semitic people of supposedly Indo-European descent with some notable Hurrian influence as well. Hyksos were known for practicing horse burials and having a chief deity who was storm god, later associated with the Egyptian god Seth.

[8] The Book of the Dead in Egyptian is actually titled, in Egyptian, rw nw prt m hrw which is more accurately transliterated into English as the “Book of Coming Forth by Day” rather than the more popular name it has been given by modern scholars and historians, the Egyptian Book of the Dead.

[9] Excerpt from THE HISTORY OF HERODOTUS, translated into English by G. C. MACAULAY, M.A. from an edition dated 1890, published by MacMillan and Co., London and New York. Note that the term Pelasgians is used by Herodotus in this context to denote the precursor Hellenic populations that lived in the area of ancient Greece prior to classical Greece in the time before the Trojan War or so, circa 1200 or 1300 BCE.

[10] Hermeticism later transformed into the pseudo-science of alchemy during the Middle Ages, becoming more associated not with spiritual transformation and knowledge but the manipulation and transformation of material objects, specifically into gold, out of which emerged modern day chemistry in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. Notable scientists who were influenced by the Hermetic/alchemical tradition include Isaac Newton from whose work with alchemy is believed to derived inspiration to his creation of the modeling and notion of gravity, as well as Carl Jung who looked to alchemy to provide a language and framework for the transformation of the soul, or individual psyche, into its full potential, a process which he referred to as individuation.

[11] Coffin Text 335a, reference from Rabinovich, Yakov. Isle of Fire: A Tour of the Egyptian Further World. Invisible Books, 2007 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isfet_(Egyptian_mythology).

[12] From http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/hesiod/theogony.htm. The Theogony of Hesiod, (ll. 713-735). Translated by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, 1914.

[13] Amun being associated with the centers of worship in Thebes and Atum being associated with Heliopolis, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_creation_myths for more details.

[14] Translation from M. Lichtheim. Ancient Egyptian Literature: A Book of Readings. Vol. 2, pp. 91-92. Taken from https://pantherfile.uwm.edu/prec/www/course/egypt/274RH/Texts/ShortAtenHymn.htm

[15] The stark contrast of Atenism relative to the Egyptian religious precepts which preceded it, as well as the timing of Amenhotep IV’s rule which coincides within a century or two of Moses’s exodus from Egypt, has given rise to considerable scholarly debate as to whether or not the monotheistic principles embedded in Atenism were a foreign construct that was borrowed and adapted by Amenhotep IV from some outside influence, or perhaps even (as was suggested by Sigmund Freud), that Atenism was the source from which Judaism’s monotheistic tradition sprung. See Freud’s 1937 work Moses and Monotheism where Freud theorizes that Moses was in fact of Egyptian descent rather than Jewish, and that he borrowed the principles of Atenism in his formation of Judaism. For more details, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moses_and_Monotheism,

[16] Source: E. A. Wallis Budge, Legends of the Egyptian Gods. Originally published in 1912 by Kegan Paul, Trench and Tribner & Co. Ltd, taken from new 2008 edition, published by The Book Tree. Introduction pg. xviii.

[17] From http://www.reshafim.org.il/ad/egypt/texts/history_of_creation.htm. Source: E. A. Wallis Budge, Legends of the Egyptian Gods.

Most interesting. As a general rule I think it could be said that religion always went from Monotheism to Polytheism, never ever vice versa.

Hi SalvaVenia. I’m beginning to think that no one of any intellectual significance in antiquity held anything other than a monotheistic conception of divinity, despite appearances to the contrary.

regards

JV

I agree. Modern times are influenced by sociology far too much.

But the whole judeo-christian movement was from poly to mono… Am I missing something?

Seen from my personal historical perspective, for sure. 🙂

Starting with Adam, it always was the concept of monotheism God inspired into man. Lateron man, by his own delusions, started to deviate from this concept and introduced polytheistic ideas.

The opposite idea is nothing more than a rather poor tale invented and propounded by sociology – and not supported by either history or logic.

Agreed, and always nice to hear from you.

I would propose however that the order was the other way around. That is to say that the ancients, prior to the advent and proliferation of monotheism, upheld a more “polytheistic” view of the divine, what in modern philosophical parlance might be called “naturalism”. And then in antiquity around the age of Christ, monotheism started to take root in first intellectual circles and later the political sphere. Initially, from a historical perspective, monotheism can first be traced back to the Hebrews (Moses and the Pentateuch), and then perhaps in parallel (or one influencing the other depending upon which source you read) the Hellenic philosophers who reached the penultimate One through reason alone (the Divine Logos or Nous/Intellect), and then in turn by the early Christians who usurped these views Judaic/Hellenic arguments for their own purposes to justify Christ as the living Logos and their doctrine of the Trinity. And then of course subsequent to that, monotheism again is (re)introduced in a supposed “unadulterated” form by Muhammad with the establishment of Islam.

Naturalism, as posed by Spinoza or Darwin for example, shares many common characteristics with what we typically call “polytheism”, or at least what typically people think “polytheism” signifies, except naturalism, given its modernity, incorporates science where the ancients simply knew no better so simply attributed what they did not know or understand about the world to the “gods”.

Indeed. The stamping out, quite brutally, of pagan forms of worship and idolatry which is one of the lasting and most influential (and ugly) legacies of the Christian tradition is much more of a socio-political narrative rather than a theological one, despite its ties to organized religion.

Religious tolerance for example was one of the great tenets of the early Muslim faith as taught by Muhammad. His approach to the creation of nations for the the good of people was based not on the conquering and (forcibly) marrying his elite and generals with the prominent wives of the myriad civilizations of his conquest, as Alexander the Great did in the 3rd century BCE, but the creation of a more holistic socio-religious state that tolerated, and integrated to at least some extent, the practitioners of the various other religions – one of the driving forces behind the spread of Islam (told from the Muslim historical perspective) despite what Western scholars would have us believe with respect to the great Muslim Conquests.