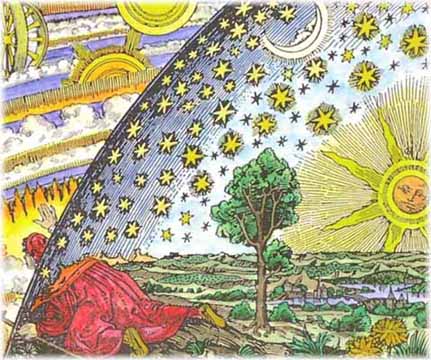

Eurasian Mythos: Establishing the Laurasian Hypothesis

These mythological narratives clearly reached back at some level or another into the pre-civilization times of the societies within which they emerged, there was clearly not only similarities between the accounts, but also clearly some “borrowing” of the narratives between and among the various civilizations which thrived during this time period in human and social evolution. They all for the most part share this common theme of the world emerging from a watery chaos, some of which (Orphic, Indo-Aryan and later Chinese myths for example) also contain the fairly distinctive metaphor of the world emerging from a great cosmic egg from which the realms of Heaven and Earth emerge, and then from this cosmic soup, or egg as the case may be, the basic elements or components of the material universe are created – Earth, Sky, Stars, Water, Heaven, etc. –providing the foundations upon which mankind and civilization itself could spring forth and flourish.

Leaving aside the fairly distinctive characteristics of the cosmogonic accounts of the ancient Chinese, there are clearly subtle and distinctive aspects of these creation narratives from the Mediterranean and Near East that reflect the various different belief systems and socio-political environments of these various cultures within which these theogonic accounts were created and established, and then preserved via various forms of writing – most of which were religious and political in nature, the distinction between the two social constructs being much less clear in antiquity than it is today. In the Egyptian, Sumer-Babylonian, Greek and Roman theogonies, for example, there clearly existed reference points and patterns of the use of mythos to establish a clear line of authority to the existing rulers, and in the Enûma Eliš, as well as Hesiod’s Theogony and Ovid’s Metamorphoses, we find the first generation of gods emerging out of this watery abyss, this chaotic primordial soup as it were, followed by the ensuing conflict among the generation of gods from which ultimate power is bestowed upon the great god of the respective civilization – Jupiter to the Romans, Zeus to the Greeks, Marduk to the Sumer-Babylonians and Amon-Ra, Ptah or Atum to the Egyptians depending upon the variant of the mythos.

Although this generational theogony from which the cosmos and then ultimately man is born is absent from the Far East accounts, namely from India and China, in China at least there is a link that is established from the founders and rulers of the various Chinese Dynasties in antiquity to the deities that presided over the universe, even if in the later tradition it stemmed from the more theo-philosophical notion of Heaven (Tiān) rather than directly to an anthropomorphic generation of deities that is so characteristic of the creation mythos from the Mediterranean and Near East in antiquity. What is clear however, is that these creation narratives that we find evidence of from the 2nd and 1st millennium BCE, is that there are many similar concepts and ideas that are put forth, and the narratives themselves also serve similar purposes, throughout virtually all of the civilizations that we have looked at in Eurasia that we have looked at – the connection of the king or ruler to the pantheon that emerges from the watery chaos from which the cosmos is created either through heredity directly or through the more conceptual framework presented by the ancient Chinese via the Mandate of Heaven. Even the Indo-Aryans established a social stratification of society that it linked back to their theogonic and cosmogonic narratives, even if they were part of a later stratification of myth (from the Laws of Manu for example).

The civilization from which Hinduism emerges for example, the successor civilization of the ancient Indo-Aryan peoples who settled in and ruled over what is today India, is historically associated with the Indus Valley, a river system from which an ancient culture could grow crops and thrive, no doubt a very similar relationship to the Sumer-Babylonians who settled in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley, the Egyptians who had such a close relationship to the Nile, and the various ancient Chinese people who had a similar close tie to the Yellow River which is closely associated with the dawn of their civilization. Clearly this close relationship to each of these respective peoples and their reliance on water for sustenance, for life, was clearly a driving factor for water being the main primordial substance from which the universe emerges in almost all of these creation narratives. The authors of the of the Vedas and Purāṇas held such beliefs as reflected in the “cosmic waters” (āpas in Sanskrit) as the source of universal creation, just as the Egyptians had their concept of Nu and the Ancient Sumerians had their Apsû – each signifying basically the same principle and each having direct etymological associations with water in some form or another.

In each of these ancient civilizations and cultures, their respective river system was the source of their crops and where they bathed and drank, just as the peoples around these river systems do today. These river systems are the very source of life, river systems that if they dried out the civilizations themselves would perish, no doubt the reason why the held the notion of water almost directly akin to life itself. In turn, the seasonal floods which no doubt framed their entire existence and relationship with the natural world, framed their idea of the passage of time and overall sense of order – both on earth and in the heavens which was used to track the seasons and passage of time itself. Therefore, it should be no surprise that we see the basic principle of water and the notion of order as it relates to the seasons and the motion of the heavens reflected in all of these ancient cosmogonic narratives. That’s not to say that there was not a borrowing or sharing of these mythological motifs that occurred between these ancient peoples – as we know there was at least throughout the Mediterranean and Near East – but then again it should come as no surprise as to how these cosmogonic narratives came to take their original shape to begin with, even if they all stemmed from the same narrative source sometime deep in pre-history.

We also find parallels with the so-called Ages of Man, as reflected perhaps in its most mature form in Ovid’s account which outlines Four Ages – Golden, Silver, Bronze and Iron – of more fierce and warlike Bronze Age which was followed by the period of the Great Flood and the subsequent re-incarnation of man in the 4th and final Iron Age which represents the current age of man. We also find a very similar thematic outline of the evolution of mankind from Hesiod’s Works and Days which outlines five ages – Golden, Silver, Bronze, Heroic and ten Iron – closely aligning to Ovid’s account and in all likelihood from which he drew his inspiration. We also find a similar account of the Ages of Man from the Laws of Manu (Manusmriti) albeit using different terminology and residing within a very different theological context. In Manu’s account, he provides a very similar description of the “downfall” of man from an era of truth and righteousness (the Krta Age) down through three more ages of man to the current age of relative relatively less righteousness and moral and ethical fortitude (the present era or Kālī Age, aka Kālī Yuga).

A similar account of the Ages of Man can be found in the Purāṇas as well, another Indo-Aryan/Hindu mythical work believed to have been composed between the 2nd and 10th centuries CE. All of which of course bear very strong similarities to the accounts of the so-called “fall of man” by Hesiod as well as Ovid, an allegorical version of which can be found in the proverbial “fall of man” from the Garden in Judeo-Christian mythos as preserved in Genesis.[1] Furthermore, we see the Great Flood play a significant role in most of these traditions as it relates specifically to the so-called “fall of man”, a narrative we find not only in the familiar account in Genesis but also in Ovid’s account of the history of man and in Sumer-Babylonian mythos in the Epic of Gilgamesh which is perhaps the source of most of the subsequent narratives, or consistent with our Laurasian hypothesis it is from an earlier source than all of these that these similar narratives find themselves rooted in all of the mythos of all these ancient peoples spread across such a wide geography (Eurasia) and expanse of time.

We can find other striking parallels between the ancient Persians and Indo-Aryans mythos specifically, not only linguistically and philologically, but also in terms of customs and rituals as reflected in their respective extant theological works from the earliest historical records we have the respective civilizations. Speaking to a very close shared heritage no doubt, linguistically identified as the Proto-Indo-Europeans from which the Indo-Iranians and the Indo-Aryans are descended. Similar to the Vedic tradition as we understand it from antiquity from the material from the oldest of the Vedas, i.e. the rituals and hymns recorded in the Rigvéda, the practice of ritual and the recitation of verses from the Gathas and Yasna clearly represents the core part of what we have come to understand as the oldest layer of the Zoroastrian faith – similarities between the Indo-Aryans and the Indo-Iranians as we understand them through the Vedas and the Gathas and Yasna abound.

Given that both of these traditions are still actively practiced, i.e. the rituals and verses and ceremonies described in the respective scripture – the Avesta of the Indo-Iranians which founded Persia civilization and the Vedas of the Indo-Aryans – we still know how some of the language documented in these ancient texts is actually pronounced, revealing striking similarities not only linguistically (philology) but also in terms of the overall content and purpose of the ceremonies themselves.[2] Gathic, or Old Avestan shares many common characteristics and similarities to Vedic Sanskrit, the writing of the most archaic of the Vedas, the Rigvéda, whose composition is also dated to the latter part of the second millennium BCE. Not only do the two languages share many of the same words and terms, but the hymns and rituals which are described in the two texts share many of the same attributes and patterns, speaking to a very close relationship between the two peoples that was captured by the authors and preservers of these ancient theological traditions, the contents of which – in the Avesta and the Vedas – describe rituals and prayers that were most certainly practiced in the early part of the second millennium BCE by these respective peoples if not even earlier.

The oldest written representations of these two ancient languages survive down to us under two different writing systems, the Vedic Sanskrit surviving in its oldest form in Brāhmī script which was used from the 3rd century BCE to the 5th century CE in South and Central Asia (and also stems from the Phoenician alphabetic system), and the Avesta in Avestan which was used from around 400–1000 CE and as already noted was specifically designed for the purpose of codifying Zoroastrian lore and practice. Given the common heritage and lineage of the different scripts which capture these ancient tongues, linguists and philologists can identify phonetic patterns and word pronunciation similarities between the two languages even though neither of which is spoken today, providing more evidence of the close association and cultural and linguistic exchange between these two civilizations reaching back into prehistoric (pre 2nd millennium BCE) times.

From a socio-cultural and even theological perspective, this linguistic relationship, both in terms of forms of writing and in terms of speech, effectively gives us two-dimensional window into the theological or religious world of the Near and Far East (modern day Iran and India) in the second millennium BCE which is the date typically associated with the Avestan and Vedic Sanskrit languages (not the texts but the languages themselves).[3]

In Zoroastrianism, again as is true with the Hindus as well, pronunciation of words and the practice of specific rituals is an important part of their worship and this is reflected in the fact that they, albeit not until the first few centuries CE, created of a specific script designed just for this purpose – namely Avestan. Avestan is written language that is a derivative of the more popular and pervasive Pahlavi script which was used by the Persians in antiquity to encode a variety of Middle Iranian Languages from around their empire. Pahlavi is derived from a more archaic Aramaic script, which in turn was derived from the same Phoenician alphabet, the very same alphabet from which ancient Greek, ancient Hebrew, and ancient Brāhmī script (a derivation of which was used to transcribe Sanskrit) was derived from, speaking to not only of course the common origins of all of the alphabetic writing systems used by these ancient peoples, but also clearly evidence of some element of cultural exchange that must have existed at some point in ancient history between these various peoples and cultures which spread and took root from as far East as Greece and the Middle East, to Persia and the Near East (the home of the Avesta) all the way to the Indus Valley region, the home of the Vedas.

Also of interest is that the Greek word for hymn or song, ymnos, which was clearly very prevalent and important in the ancient Hellenic world as illustrated in the widespread and well documented traditions of Homer, Hesiod, and Orpheus, means almost the same thing as its linguistic counterpart to the East – yasna to the Indo-Iranians and yajña to the Indo-Aryans. In the Greek tradition however, the connotation of the word is somewhat devoid of the of the notion of ritual or sacrifice, perhaps because the sacrificial aspect of the hymns themselves was dropped by the Greeks, at least outside of the mystery cult traditions of which we know little about given the veil of secrecy within which these practices were shielded. One could argue that the Greek word for hymn or song, ymnos, which represented such an integral part of the ritualistic and theological tradition even in Greece – as reflected in the prevalence and importance of the hymns of Hesiod and Homer in the Hellenic philosophical and cultural tradition – could be and probably was a direct derivative from these two relatively more ancient religious systems to the East. This is perhaps evidence of much closer ties of these cultures from a religious and theological perspective. It is perhaps not that far-fetched to conclude that this very similar word or term that found its way into the languages of these geographically dispersed civilizations in antiquity – from Greece/Ionia in the Mediterranean and Near East to the Persian/Iranians in Asia Minor to the Indo-Aryans/Hindus of modern day India – that carried such cultural and theological import is evidence of perhaps more cultural exchange and intellectual communication between these cultures in the 3rd and 2nd millenniums BCE than historians, academics and classicists typically presume.

What is certainly unique to the Greek/Hellenic tradition however, i.e. Hellenic mythos, was that they more than any other ancient civilization were obsessed with the idea that the universe could be, and should be, placed upon rational grounds wherever possible. It was this idea, one of the hallmarks of the ancient Hellenes, or “Classical Greece” as it is typically referred to, that contributed toward the birth of reason which becomes one of the hallmarks in turn of Western civilization as a whole – what came to known from a philosophical perspective, perhaps most pronounced in the Stoic tradition which in turn provided the basis for Judeo-Christian theology , as Logos. Reason, or again Logos, was the metaphysical lever as it were, that was used to support the characteristically Hellenic pivot away from the more ancient and pre-historic theogonic and cosmogonic narratives – i.e. again mythos – that had persisted for thousands of years prior to the advent of philosophy. While the Hellenes no doubt held fast to the mythological traditions and worship of the respective gods therein as espoused and put forth in the lasting works of Hesiod and Homer for example even during the height of philosophical influence in the Hellenic world, they still nonetheless, again characteristically, provided the socio-political environment within which the Hellenic philosophical tradition could flourish more or less despite its generally unfavorable position toward the political establishment as it were. The underlying friction of the two traditions – the philosophers on the one hand and the political establishment or authority on the other – from a socio-political perspective is illustrated for example in the execution of Socrates by the Athenians, a conviction that was handed down by the Athenian council toward Socrates because of allegations against him related to impiety as well as corrupting the youth no less.[4]

It is perhaps no accident then, that Socrates plays such a pivotal role in the establishment of the philosophical tradition in ancient Greece, in the Hellenic world throughout the Mediterranean, that was to have such a long standing and powerful imprint on Western philosophy and theology as it evolves into its present day monotheistic variants in Christianity, Judaism and Islam most notably. This reason was referred to within the Hellenic philosophical tradition originally as wisdom, i.e. sophia, which sits quite literally at its very heart in the root of the word that was used to describe the tradition itself – – i.e. “philo” + “sophia”, or “lover of wisdom”, i.e. philosophia – a name which according to tradition is attributed to by Pythagoras himself, a sage from Hellenic antiquity that is considered by many (author included) to in many respects be the father of the Hellenic philosophical. In other words, it was the Hellenic philosophical tradition more so than any other in the ancient Mediterranean world perhaps, that characterized this separation between theology as it was conceived in antiquity as mythos, and authority and power.[5]

The Hellenes from the ancient Mediterranean no doubt were the first to establish the supremacy of reason and logic, verifiable truth, over “myth”, a belief system that had carried mankind through the darkness of pre-history for thousands of years. In the Hellenic philosophical tradition, these ancient belief systems were not discounted altogether, but they were nonetheless held to be less true, less real as it were than philosophy proper (philosophia), which again was founded upon the principles of reason and logic, the latter of which was a new discipline entirely that emerged in the Mediterranean as well as the Indian subcontinent at around the same time as writing and advanced civilization as far as we can tell. This is what Plato and Aristotle in particular took care to distinguish from eternally verifiable or rationally deduced truths as it were, what they called out as “opinion” or “belief” which was defined in contrast to, and was considered to be epistemologically less significant than, wisdom, again sophia, which was based upon reason, the new found god of the Hellenes you might say.

Much of the mythos of these ancient peoples, the rituals and the priesthood, was intended to bifurcate society into those that knew god, and those that didn’t. And this established order or authority of the one class of people over the other. Even with the Greeks, the priesthoods had power and represented established authority to some extent, although with the advent of their democracy, which to some extent grew hand in hand with their philosophy and the evolution of their world view, they moved away from this old guard of authority which had its source in the priesthood and worship of the gods. Most certainly with the Sumer-Babylonians and the Egyptians this connection was there as the leadership relied on the authority of these priests to maintain their power. And it was the people’s belief in the existence of the gods, and the priests’ direct communion or connection with these deities, that kept the peace as it were and established the norms and various stratifications and classifications of the society, in particular firmly delineating those who held power and those that did not.

This subtle distinction, what you might call the very first example of the separation between “church and state” (which although doesn’t precisely describe the actual situation is the best modern analogy perhaps that can be found), the break from political authority resting on divine authority, theology and/or mythos, turned out to be one of the most important, significant and lasting contributions of the Hellenes to Western civilization. One that came at the blood of Socrates no less and one that marked a significant break and divergence from pre-historic society which was founded on these principles more or less. For it was this separation of mythos from politics or royalty, attributing the mythological account to divine inspiration as it were, perhaps the hallmark of Hellenic philosophy, that laid the foundation for the creation of philosophical traditions that formed the basis of academia as we understand it today, and then much later in the post Enlightenment Era, Science.

But at the same time the parallels between all of these ancient mythological narratives from the Mediterranean and Near East, all beginning more or less their creation narratives of the emergence of order from chaos, all of these ancient civilizations nonetheless were no doubt compelled to answer these basic questions – Who are we and from whence we came? The emergence of universal order, i.e. the kosmos, out of chaos and the “watery abyss”, which provided for the ground and basis for the creation of mankind and in turn civilization as we understand it most clearly after writing is developed and we start to have direct intellectual evidence, breadcrumbs as it were, from the minds of these first philosophers from Eurasian antiquity, and then – through the use of language itself as a tool for advanced abstract thought, thought which could persist from generation to generation, that could be transformed and evolve through the generations as the teachings were passed down from teacher to student, transformed over time into advanced systems philosophy, intellectual systems and paradigms that that did not have to be encapsulated in myth so that it could be supported by oral transmission techniques, the technological advancement that has served mankind for thousands of years, millennia even, before the invention of writing and the alphabet – in turn the question of how society as a whole should be structured, based upon reason rather than monarchical decree or social stratification that had been in place for the preceding generations, political philosophy or what in the Hellenic and Western tradition comes to be called practical philosophy, was then also addressed.

These shared characteristics and challenges in fact we find covered and explored in the very first philosophical works that we see throughout antiquity across all of Eurasia – from the Mediterranean to the Near East and Persia to the Indian subcontinent and the Indo-Aryans and Hindus to the Far East and China. They all struggled with the same questions and problems more or less, and they all pivoted from mythos to philosophy. Each culture and society, each philosophical tradition as it were, might have all come up with slightly different answers – each tailored to their own nuanced and distinctive cultures and histories – but they all addressed the fundamental problem of rationalizing cosmogony and theogony more or less, as well as establishing the (rational and moral) basis for socio-political order.

As further evidence of our Laurasian hypothesis, we also find across many of these ancient mythos from across Eurasia the motif of the cosmic egg from which Heaven and Earth are formed and the universal order, i.e. the cosmos, is established. In the Orphic tradition for example, a tradition which in many ways was the hallmark of Hellenic theogony (outside of the lyric poetical tradition established by Hesiod at least) we see the protogenital anthropomorphic man or figure, i.e. Phanes or Protogonus come forth from this cosmic egg:

O Mighty first-begotten, hear my pray’r,

Two-fold, egg-born, and wand’ring thro’ the air,Bull-roarer, glorying in thy golden wings,

From whom the race of Gods and mortals springs.Ericapæus, celebrated pow’r,

Ineffable, occult, all shining flow’r.

From eyes obscure thou wip’st the gloom of night,

All-spreading splendour, pure and holy light

Hence Phanes call’d, the glory of the sky,

On waving pinions thro’ the world you fly.

Priapus, dark-ey’d splendour, thee I sing,

Genial, all-prudent, ever-blessed king,With joyful aspect on our rights divine

And holy sacrifice propitious shine.[6]

The protogenital deity Phanes, aka Protogonus, in the Orphic theogony narrative, illustrated in the above passage from the Hymns of Orpheus, is the first and foremost of the immortal beings who emerges, self-created, from the great cosmic egg from which the universe is born and from which Heavens and Earth are created. Phanes here is depicted as this great mythological winged creature who has the attributes of both man and beast, depicted in some accounts as having 4 eyes, four horns, and the body of a serpent, a bull, a lion, and a ram. It is from this fist great primordial being, both male and female, who emerges from the great cosmic egg of creation, that the universe begins to unfold and the initial generation of gods springs, i.e. theogony.

We see essentially the same narrative across all of these ancient civilizations that as far as we know, at least from the archeological and written records, had no significant cultural contact with each other – at least not this far back in history (the Egyptian and Mediterranean cultures being the exception here of course). We see an almost direct mythic parallel for example to the Orphic cosmogony surrounding the protogenital man, Pángǔ from ancient Chinese mythos, who emerges from a cosmic egg after a great deluge of sorts (i.e. Great Flood) which destroys mankind, and then establishes universal order through Yīn-Yáng, the primordial first principles as it were, after which the natural world and civilization emerges, born again as it were out of the great cosmic egg. We see virtually the same cosmic egg based theogony in ancient Egypt as well, in the tradition surrounding Hermopolis that establishes creation from and out of the Ogdoad, or Great Eight, which also emerges out of a cosmic egg, the first primordial deity being the god of the Sun, Ra, in that account.

Furthermore, we see striking similarities in the cosmogonical narrative in the Indo-Aryan tradition as well, as we see it preserved in the Rigvéda, wherein an epithet of Prajāpati, the creator of the universe in many of the Vedic hymns, is Hiraṇyagarbha, which means literally “golden egg” or “golden womb”. The same motif can be found in the famed Laws of Manu, i.e. Manusmriti which provides much of the moral and socio-political foundations of modern Hindu society, akin to Plat’s Republic in a way. The Laws of Manu contains in its introductory chapter a cosmogonic and theogonic narrative, establishing the basis of the moral and ethical precepts, and again socio-political framework, for what is the core of the text. Here the tale of the Ages of Man, the Great Flood and emergence of the cosmos out of a great cosmic egg are also prevalent.[7]

There was also the common theme of a pantheon of deities that emerge through a theogony that is rooted in the cosmogony as it were, each of whom represented one of the basic natural principles – again Earth, Air, Water, Fire, Sky, Moon, Sun, etc. – which all of these ancient peoples were subject to within the context of Nature itself, and all of whom became manifest in these theogonies and were worshipped in order that their duties, and the cosmological order really, be kept in balance. These very same deities, these basic primitive forces which were layered into these very same theogonic and cosmogonic narratives, not only created the universe with their divine powers, but they effectively represented these various aspects of the universe, Nature, as well. This common theogonic narrative we see co-emergent with civilization itself in Eurasian antiquity in fact, a hallmark of the very beginning of each of these respective great civilizations – the Egyptians, the Hellenes, the Romans, the Indians, etc. – a narrative, collectively mythos, that provides not just an explanation as to how the world, and mankind, came into existence, but also providing the moral and ethical basis, with the notions of order and balance, for society which according to the ancients at least should reflect the harmony and order of the cosmos.[8]

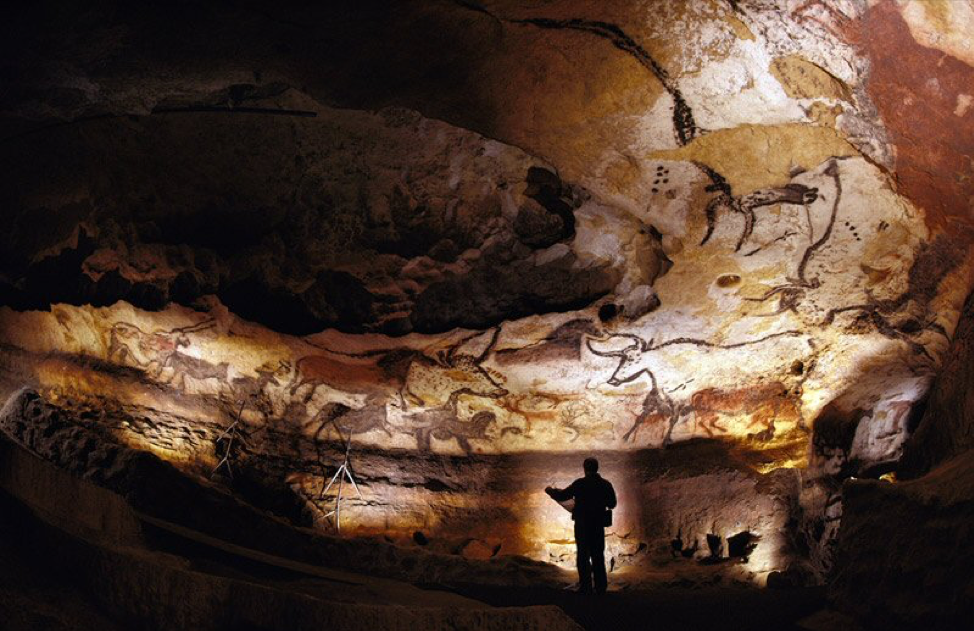

These gods were different for each of the ancient civilizations, and they were created in different orders and had different relationships with each other, no doubt reflecting the different underlying importance of the principles which they represented for each of the respective societies. But these deities were a key part of the establishment of the world order nonetheless. Or perhaps better put mankind was made in the likeness of these deities, albeit mortal. So while these deities Gods were immortalized, they were also anthropomorphized as well, for that was the only metaphysical construct, or at least the easiest to explain and understand, that resonated with these ancient peoples. And because these immortals had human characteristics, they therefore had human attributes, wants and needs as well, needs that had to be provided by those that worshipped them. This effectively describes the relationship between the peoples of pre-historical Eurasia, from the Upper Paleolithic to the Bronze Age, and their gods which we look upon from our modern, monotheistic lens – as did the Greeks as well – as pagan and barbaric religious practices.

There is no doubt that each of these ancient civilizations had an inherent need or desire to understand how order and in turn mankind emerged from the grand mystery of the universe, from nothingness or the eternal void. Clearly all of these ancient civilizations had a yearning to understand or formulate some sort of coherent story line that explained how the world was born and how mankind came to be, and how this understanding was to be leveraged and used to support the development of advanced societies, societies that were in fact bound by their mythos and its associated cosmogony and theogony – the worship of these gods that formed the basis of creation and sustained and supported the stability and order of Nature so that their society and civilization, and ultimately their own life, could prosper. As it turns out, at least in the Mediterranean and Near East, it is clear that each of these ancient civilizations shared many of the same ideas, concepts and notions, i.e. mythos, as to how the universal order was established as well as how it was to be properly maintained. Whether this was a result of cultural and theological diffusion, i.e. borrowing, or because they all started with a very similar story line that evolved in different times and places for different peoples is hard to say, but the extent of the commonalities as well as the specificities of the commonalities themselves certainly indicates that a shared origins hypothesis, as we have proposed (following Witzel) in what we are calling the Laurasian hypothesis certainly looks like the best possible explanation – given what we now know about ancient human migration via the study of the human genome and the continued lack of archeological, written or other evidence that suggests any direct cultural exchange between these ancient civilizations that were geographically so dispersed throughout Eurasia.

[1] Manu’s Code of Law: A Critical Edition and Translation of the Mānava-Dharmaśāstra. By Patrick Olivelle. Oxford University Press 2005. Chapter 1 verses 68-85, pgs. 90-91.

[2] While Zoroastrianism is not nearly as popular or widespread as Judaism or Hinduism, it still nonetheless is still practiced in some small pockets of the world, particular in the Near East from which it originated, and therefore we still retain a window into the theological beliefs and practices of these ancient peoples, as well again their original language, as we do the ancient Hebrews and Vedic priests (Brahmins) through their worship, rituals, and belief systems which are still practiced today as well.

[3] Compare the Avestan word yasna which has a direct correlate in Sanskrit yajña for example, both of which denote a sacred, ritualized practice of chanting or hymns (associated with mantra in the Vedic tradition) that in many cases also involved some form of animal sacrifice or some other oblation in their respective religious traditions (like soma juice for example), and both terms form a core part of the respective traditions, so much so in the Zoroastrian tradition that a core part of the Avestan literature bears its name, i.e. the Yasna. Also, the Sanskrit word soma, used to describe a plant or drink substance which constitutes an integral part of many of the rituals described in the Rigvéda has a direct counterpart in the Avestan language, i.e. haoma. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soma.

[4] The death of Socrates is the subject of Plato’s Apology.

[5] It should be pointed out however, that while the ancient Chinese did in fact foster a similar separation between authority and philosophy, the two disciplines if we can call them that were not quite so separated as they were in ancient Greece – the scribes and philosophers of ancient China were for the most part connected to and served the courts of the various rulers and dynastic courts so while they were free to pursue knowledge and study the “Classics” as it were, they still had to do so with the blessing, and purposeful alignment, with the rulers of the people.

[6] Hymns of Orpheus. Translated by Thomas Taylor. 1792. To Protogonus, or the First Born. From http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/hoo/hoo10.htm.

[7] For a brief summary of the cosmic egg motif in theological accounts of creation see Wikipedia contributors, ‘World egg’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 4 July 2016, 18:55 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=World_egg&oldid=728337753> [accessed 5 September 2016]. E. J. Michael Witzel also offers an account of the cosmic egg motif across a wider variety of civilizations in antiquity and throughout the world in his The Origins of the Worlds Mythologies (Oxford University Press 2012), pgs. 121-124.

[8] The ancient Chinese are perhaps the only exception to this basic theogonic narrative that is so characteristic of ancient civilization and cosmogony. We say perhaps here because it is possible that these ancient deities, and potentially a surrounding theogony and mythos, were worshipped in the Shāng Dynasty era in the second millennium BCE but as of now the evidence is lacking – archaeological, written or otherwise.

Reblogged this on Die Goldene Landschaft.