From the (Ancient) Far East: The Translation Challenge

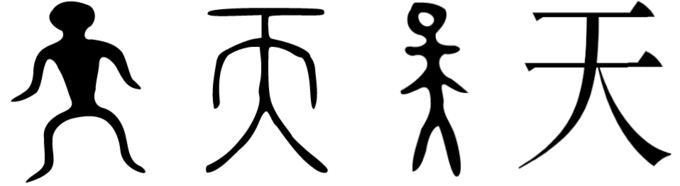

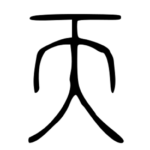

We see the first evidence of Chinese writing, pictograms or logograms on bronze and bone artifacts from the last years of the Xia Dynasty (2070 – 1600 BCE), almost four thousand years ago. This writing system, the foundations of which became the what we now refer to as Chinese “characters”, were highly symbolic and hieroglyphic in nature, appearing in the archeological records on Bronze castings, tortoise shells, and cattle bones, the latter of which were primarily used for divination purposes. Inscription on Bronze castings (金文, literally “text on metal” or “text on gold”) typically represented a clan or family membership as well as socio-political status. This ancient form of writing is referred to sometimes in the academic literature as Oracle Bone Script, or Shell script (甲骨, literally “text, “文” on shells, “甲” and bones, “骨”) a form of writing which was used up until the early Western Zhou Dynasty (1046 – 771 BCE).[1]

The successor to these forms of writing were Seal script (篆書, literally “decorative engraving script”) which in turn evolved into Clerical script during the Warring States Period (c. 475 – 221 BCE) and Qin Dynasty (221 – 206 BCE) periods of Chinese antiquity.[2] It is during the short reign of the Qin Dynasty that (most of) what we consider to be modern China was unified post Warring States Period and in turn standard forms of writing and literature were established.[3] Most of the classic literature we have from China antiquity was compiled in the first millennium BCE and written on bamboo or silk in a written language that has come to be known as Classical Chinese[4], also known as “Literary Chinese”, a written form of the Old Chinese language which was used for almost all formal writing in China up until the early 20th century.[5]

As Seal script emerged as the written standard, used primarily by an educated aristocratic class of scholars who were typically associated with the various courts of the ruling bodies, the foundational set of standard Chinese characters was established that were to be used for over two thousand years that would eventually evolve into a set of even more sophisticated ideograms and morphemes which were capable of encapsulating and transcribing all of the various languages that were prevalent in China and the surrounding regions throughout its longstanding history. One of the distinguishing characteristics of ancient China in fact, given its vast regional territories and various peoples and cultures which inhabited what we today call “China” in antiquity, was the persistence of a single system of writing that could be used to encode and transcribe all of the various languages that were spoken throughout classically Chinese territories in antiquity, some of which were not even from the same (spoken) language family.

The modern Chinese character set includes over 50,000 characters, and has evolved to support the transcription of a wide array of modern spoken languages which include of course Chinese, but also include other Asian (spoken) languages such as Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese along with a host of other Chinese dialects like Mandarin. The writing system has of course grown increasingly complex to support these broad linguistic features over the centuries, millennia really, and given that it is not based upon an alphabetic system as we are accustomed to in the West, it is quite foreign to Westerners and is very difficult to learn. Specifically, and of particular relevance to this work which tries to ascertain and comprehend the meaning of ancient Chinese texts, the ancient Chinese forms of script can be very difficult to translate, really transliterate, given the very different nature of the symbols themselves as well as the unique nature of some of the characters and symbols that are only found in the ancient texts, the meaning of which can only (potentially) be understood by tracing, if possible, the etymology of the specific characters back through Oracle Bone and Bronze inscriptions.[6]

At the same however, the unique nature of written Chinese also provides us with an almost unbroken lineage of ideograms and logograms that reach directly back into deep Chinese antiquity, something that cannot be said of the writing systems that survive in the West, the Indian subcontinent included. In some cases certain characters, words or phrases can be traced all the way back through modern Chinese characters through their Traditional Chinese counterparts, to their Clerical script representations, and sometimes even as far back as Seal script or even Bronze or Oracle bone inscriptions which represent the earliest forms of writing of the ancient Chinese.[7]

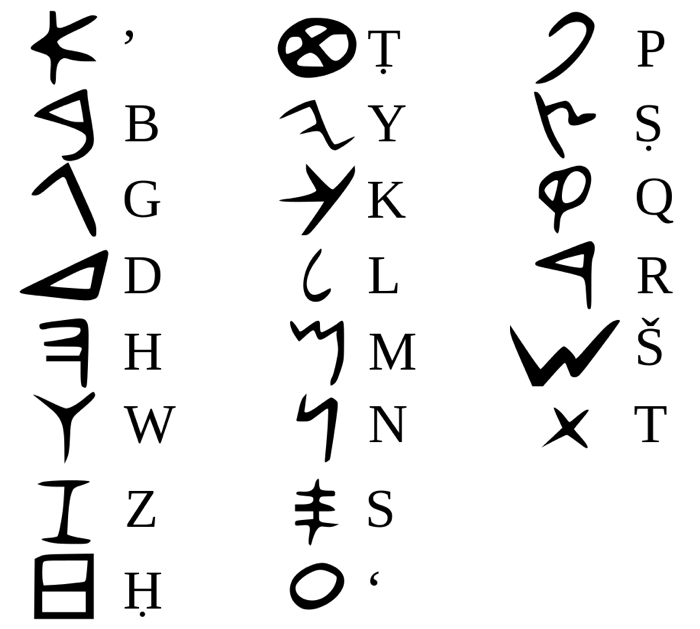

The evolution of the Chinese character set as a device for documenting and transcribing spoken languages in the Far East (as juxtaposed with the more precise alphabetic systems of writing that were adopted by the West, the majority of which are believed to have derived from the Phoenician alphabet) is not only an artifact of the longstanding and continuous evolution of the writing system itself, but also again reflects the underlying requirement of the written language to continuously support a wide variety of spoken languages by the various tribes, populations and civilizations that were incorporated into imperialistic China at various stages in its social and political development throughout its history – over the course of some five thousand years. This provides for a challenge in translating, again really transliterating, into modern Western European languages but also provides a unique window into the minds of the ancient Chinese peoples that used these archaic and more primitive forms of writing, and even to some extent provides a window into pre-historical, i.e. before the evolution of advanced systems of writing, mindset.

These unique features of written Chinese while leaves us with a very complex and notoriously difficult transliteration challenge into modern Western languages, nonetheless it can in some cases provide us with unique insights into what these symbols actually meant to the ancient Chinese authors who used them, i.e. what they actually might have “symbolized”. So although the ancient Chinese forms of writing are undoubtedly less specific than their counterparts to the West, and of course do not lend themselves to a simple direct translation in many cases, they do nonetheless – at least as far as the ancient classical texts are concerned – provide a platform for communicating a much more open and far-reaching set of ideas that in some cases reach as far back as prehistorical China. These characteristics are unique to the Chinese system of writing and while they provide again for some very interesting transliteration challenges, do again nonetheless in some cases yield greater insight into the ancient belief systems of the prehistoric peoples from which the classical Chinese civilization evolved from.[8]

Adding to the complexities and subtleties of the translation of ancient Chinese forms of writing, most especially ancient Chinese into modern Western European languages that are based upon the Roman and Latin alphabet, we do not find anywhere near the same type of semantic clarity – punctuation, verb tense and sentence construction for example – that we have come to expect in our modern Western languages, or even in classical Latin or Greek. Furthermore, in many cases, again in particular in some of the classic Chinese philosophical literature, symbols, characters or words can have multiple meanings, many of which could be in play for a given sentence, passage or verse in a given context. While this gives the author a lot of power to convey ideas and thoughts with a minimal set of characters or words, it nonetheless makes the process of translating Chinese, especially Old Chinese in the Classic script, sometimes excruciating difficult where a specific set of characters, word or phrase can have, and may in fact be designed to have, many possible renderings or meanings.[9]

Furthermore, and reflective of the challenges that persist in the “Romanization” of Chinese terms and words from the Chinese alphabet into our own, there exist two different approaches to this problem, hence the continued need for, and proliferation of, different Romanization transliterations of Chinese words and terms into English even today that students of Chinese history and philosophy must familiarize themselves with in order to understand what Chinese word, phrase or text the (Western) author is actually referring to. The first method of Romanization of Chinese words that was standardized in the West, and perhaps even still the most widely found throughout the literature, is the “Wade-Giles” system. This system was created in the mid 19th century and therefore has been in use for some time and dominates most of the Western academic literature regarding the ancient Chinese up until the last few decades, where it has begun to be replaced by a more modernized version of Romanization called the “Pinyin” system. This system was created by the Chinese government in the 1950s and was adopted by the ISO (International Organization for Standardization) in 1982 and is generally used in almost all modern academic literature, at least in the last twenty years or so. One still finds references of terms using the old Wade-Giles form however, and in order to properly wade through materials on ancient Chinese history and theo-philosophy, one must be familiar for the most part with Chinese terms in both systems of transliteration[10].

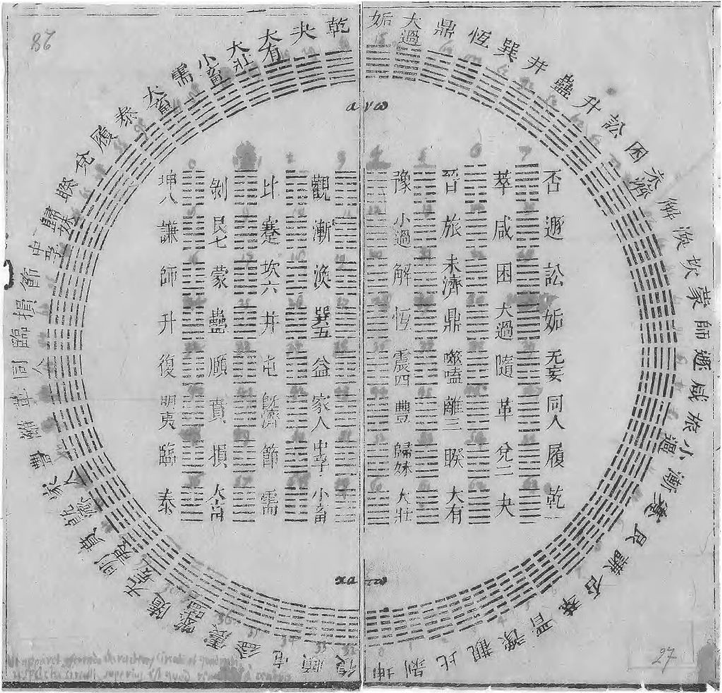

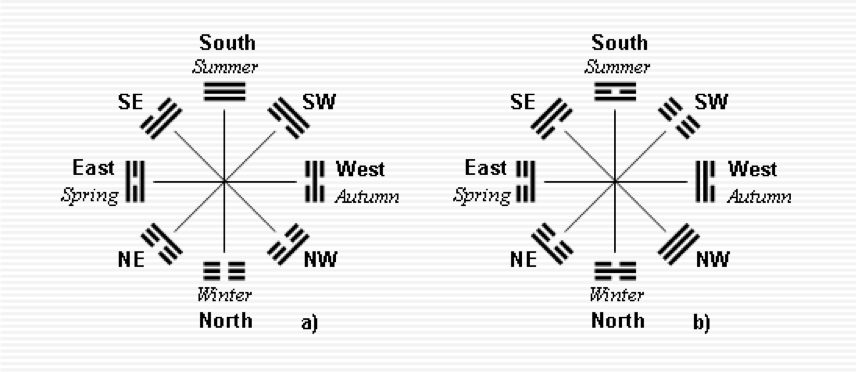

As a specific illustration of the challenges presented by the existence of two different methods of Romanization of Chinese words, take for example the name of the famous ancient philosopher Lǎozǐ (Pinyin), or alternatively in the more familiar Wade-Giles form, Lao-tzu. For most of the twentieth century, his famous work was transliterated into English using the old Wade-Giles form, i.e. the Tao Te Ching which is how the work is predominantly known to the Western reader. The title of the work however has now been replaced in almost all of the modern academic literature with the Pinyin Romanization form, i.e. the Dàodé Jīng or Daodejing. We confront the same issue with the Chinese classic the I Ching (Wade-Giles) versus the Pinyin form Yìjīng as another example. The former Romanization approaches represented by the Wade-Giles method, e.g. the Tao Te Ching and I Ching, in all likelihood represent terms that the reader is most familiar with, reflective of the fact that they are the more widely used terms even today outside of academic circles.

The student of ancient Chinese history and philosophy is therefore confronted with the very unique problem of having to familiarize themselves with both forms of Romanization as there are still many works that continue to be relevant in the study of ancient Chinese history and philosophy use the old Wade-Giles system, and these forms of Chinese words are again the most familiar to the Western reader as they have been used for the longest amount of time and are the most pervasive in the literature. Meanwhile again almost all modern academic (properly) use the Pinyin method of transliteration, sometimes not including the reference to the old Wade-Giles forms of the words or titles of the text. This for example makes it much more challenging to search and find digitally certain ancient Chinese words or texts in their Romanized form as compared with ancient Greek literature for example which have had standard Romanized forms for many centuries or of course ancient Roman/Latin words or names of text which require no form of Romanization at all. This is unique challenge that is presented to the student of the ancient Chinese intellectual and philosophical traditions and is a byproduct of the distinctive and altogether unique nature of their system of writing, language, and worldview in fact, relative to ours in the West.

As a further and more illustrative example of the translational difficulties and insights when dealing with specific passages and words from ancient Chinese texts, let’s look at two translations from two different groups of scholars of the famed Dàodé Jīng, one of the earliest and most influential of the ancient Chinese philosophical texts attributed to Lǎozǐ, traditionally accepted to have been compiled sometime in the 6th century BCE and the foundational treatise of Daoist philosophy. We look at here specifically at verse/chapter 42 which is one of the most oft quoted and infamous of passages from the Dàodé Jīng dealing with cosmogony, or universal creation.

The first translation is from Robert G. Henricks, Professor Emeritus of Religion at Dartmouth who specializes in ancient Chinese philosophical research (Sinology) from 1989, some 15 years after the discovery of Mawangdui Silk Texts which included among other things newly discovered versions of the Dàodé Jīng which greatly expanded our understanding of the manuscript and textual tradition that surrounded this classic work. His translation is smooth and elegant and illustrates the poetic and lyric nature that was no doubt intended in the original text.

Like most texts from classical antiquity however, it was transcribed not only to capture and document the longstanding oral tradition from which it derived, but in fact, perhaps as byproduct of the transcription itself, established some of the core conceptual metaphysical and philosophical underpinnings, from a linguistic perspective, that have now come to form the basis of Daoist philosophy.[11]

The Way gave birth to the One;

The One gave birth to the Two;

The Two gave birth to the Three;

And the Three gave birth to the ten thousand things [wànwù].

The ten thousand things carry Yīn on their backs and wrap their arms around Yáng.

Through the blending of ch’i [qì] they arrive at a state of harmony.

The things that are hated by the whole world

Are to be orphaned, widowed, and have no grain.

Yet kings and dukes take these as their names.

Thus with all things – some are increased by taking away;

While some are diminished by adding on.

Therefore, what other men teach,

I will also consider and then teach to others.

Thus, “The strong and violent do not come to a natural end.”

I will take this as the father of my studies.[12]

The next translation we review as a point of comparison comes from Roger T. Ames, Professor of Chinese Philosophy from the University of Hawaii and editor of the journal Philosophy East and West along with David L. Hall Professor of Philosophy from the University of Texas El Paso. Their translation was published in 2003 after a further discovery of “Bamboo texts” known as the Guodian Chu Slips in 1993 which included among other things an even older version of the Dàodé Jīng than had been previously known that contains some significant departure from the “standard”, “received” version of the text, shedding light on the textual transmission of ancient Chinese works in general and speaking specifically to the various versions of the Dàodé Jīng that must have been in circulation in the first few centuries after the text was initially transcribed.

The Guodian Chu Slip versions of the Dàodé Jīng include some differences not only in some characters that were used relative to the more standard, orthodox version, but also even a different chapter ordering than the “received” versions of the texts.[13]

Way-making (dao) gives rise to continuity,

Continuity gives rise to difference,

Difference gives rise to plurality,

And plurality gives rise to the manifold of everything that is happening (wànwù).

Everything carries Yīn on its shoulders and Yáng in its arms

And blends these vital energies (qì) together to make them harmonious (he).

There is nothing in the world disliked more

Than the thought of being friendless, unworthy, and inept,

And yet kings and dukes use just such terms to refer to themselves.

For things, sometimes less is more,

And sometimes, more is less.

Thus, as for what other people are teaching,

I will think about what they have to say, and then teach it to others.

For example: “Those who are coercive and violent do not meet their natural end” –

I am going to take this statement as my precept.[14]

Irrespective of the very interesting and cosmological and metaphysical content reflected in the above passage, what should immediately strike the reader is that if one were to read the two translations independent of each other, without knowing that they come from the same “textual tradition” surrounding the Dàodé Jīng, i.e. the same work basically, one could easily conclude that the translations were from two different works entirely. Interpreting what the passage means then, or the meaning that the ancient author is trying to convey, and how this passage fits into the philosophical tradition and milieu from whence it originated, and in turn comparing the underlying philosophical content with other extant ancient textual traditions, becomes a very difficult and complex problem indeed. A problem which is again unique to the study of ancient Chinese philosophy.

What that leaves us with, at least in the Western academic tradition with our reliance on, our dependence and assumption upon, “philosophy” as a written, coherent and logically sound belief system that explains the natural world and mankind’s place within it, and that also has some sense of semantic clarity which permits some sense of definitional transference into modern English that allows to connect various ancient terms, words and ideas throughout the evolution of the philosophical tradition as a whole as well as into modern Western European philosophical parlance, is a bit of a conundrum really. What we want to do, what we’re inclined to do in studying the Chinese philosophical tradition in antiquity, is to attempt to parse form the ancient texts a cosmological, metaphysical and ultimately theo-philosophical belief system that maps somehow onto modern metaphysical and philosophical conceptions, even if these conceptions have ancient theo-philosophical counterparts – i.e. analogous to what has been done with the Greco-Roman theo-philosophical traditions which given it’s straight lineage from Greek to Latin to English provides for greater insight into the underlying worldview, the underlying meaning as it were, of the ancient authors who wrote the definitive theo-philosophical works in question. This is a task of a very different order when studying the ancient philosophical works of the Chinese however.

Given the predominance of so many disparate and competing cultures and societies that existed from say 4000 BCE to 500 CE in the geographic region that has come to be known as China today, the various languages, cultures and belief systems were synthesized, integrated and sometimes altogether destroyed or totally assimilated in various phases and by various dynastic cultures as they slowly consolidated the vast regions and territories which later came to be known as the Chinese Empire – first with the prehistoric Xia Dynasty established by the Yu the Great, then to the famed Shāng Dynasty, then on to the Zhou Dynasty which is when most of the Chinese Classics we know today were first written down, to the Qin Dynasty which consolidated the Chinese empire after the Warring States Period, then into the Han Dynasty where Confucian philosophy was officially adopted by the state and the period of Chinese antiquity basically comes to an end. Each of these dynastic rulers drew more or less from the varying philosophical traditions to not only guide but in some sense legitimize their rule, i.e. the so-called Mandate of Heaven, and what evolved alongside this cultural expansion, synthesis, assimilation and expansion was their system of writing that had to be extraordinarily flexible, broad based and inclusive to encompass the various languages and ideologies which assimilated into classically “Chinese” culture.

Many languages were and continue to be spoken in China, and all of these languages needed to be codified, written, transcribed in a single written form, and yet the writing system still had to incorporate and assimilate the various textual and written traditions that harkened back to Bronze Age China – the beginnings of which are captured on first on tortoise shells and ox bones – Oracle Bone script and the slightly more advanced form of script found on Bronze artifacts referred to as Bronze script. This system then in turn became more advanced and is found in the archeological records on Bamboo and Silk and is commonly referred to as Seal script, which was then followed by the development of a more sophisticated and advanced (and in turn complex) system of writing called Clerical script which forms the basis of Traditional Chinese which are still in use in China and many other countries in the East today.

The scriptural tradition (not scriptural with the sacred connotations we are used to in the West but scriptural in the sense that the ideas are written down) evolved alongside the culture and socio-political evolution right from the beginning, providing for a framework of continuous (written) linguistic heritage that is unique to the Far East. But at the same time it does not lend itself to the sort of logical and semantic precision that we are accustomed to seeing and leveraging when we analyze ancient Western philosophical works. This is a very unique and sometimes frustrating problem when studying the ancient Chinese theo-philosophical development, particularly when approaching the intellectual developments from a classical Western academic mindset. So while the spoken language family of the people of China typically falls in the Sino-Tibetan language family, part of the language tree that has many diverse siblings and offspring linguistically and phonetically speaking, the written language dates back to the dawn of civilization in the Far East, and slowly incorporated various symbols from different sub-cultures over time as they were assimilated into Chinese culture as a whole, and therefore the Chinese were in fact almost forced to keep a more primitive linguistic structure, one which is quite foreign to the phonetically driven alphabet systems we are so used to working with in the West.

This unbroken linguistic and cultural lineage however, has supported and fundamentally reflects, a certain level of cultural open mindedness and inclusivity. The writing system had to be inclusive and far reaching in order to support the assimilation and consolidation of the various languages that were spoken in ancient China, and as a result, their system of writing had to incorporate certain symbols which reflected a certain, specific given meaning, more or less, and may or may not have a phonological counterpart (how that word sounds). In this system, semantic and ideological clarity is yielded for linguistic flexibility and this characteristic of the Chinese (written) language has both its strengths (in term of flexibility) and weaknesses (in terms of lack of clarity), depending upon one’s perspective. This context and associated linguistic attributes must be taken into account when trying to understand the true meaning and import being conveyed by the ancient authors, authors whose works survive for the most part in some of the oldest forms of the Chinese language and were attempting to transcribe and capture living and breathing oral traditions that reached even further back into Chinese antiquity.

It is interesting to note that the view from the Far East with respect to how they interpret their original theo-philosophical works – like Lǎozǐ’s Dàodé Jīng or the Confucian Analects for example – stands in fairly stark contrast to the more dogmatic interpretive theological tradition that is such a hallmark of the West – the Abrahamic religious traditions in particular with their strict interpretation of scripture and unwavering belief in the words of their respective prophets and their “divine” revelation. It is quite odd in fact that with our cultural history in the West that has virtually reinvented systems of writing every 700 years or so, that such credence and divinitive powers have been given to the various texts and words of the various prophets – i.e. the Bible or the Qurʾān for example – while a linguistic tradition like that of the Chinese that has essentially remained fairly constant over the course of millennia and has systematically absorbed symbols and phonemes from a broad range of peoples within its geographic borders, still remains quite flexible with respect to interpretation of, and fundamental weight applied to, the actual words and symbols that are used to convey the meaning of the ancient Chinese philosophers which provide the theo-philosophical basis of their culture even today.

[1]See http://www.ink-treasures.com/history/calligraphy/chinese-calligraphy/calligraphy-scripts/bronze-inscriptions/, http://www.ink-treasures.com/history/calligraphy/chinese-calligraphy/calligraphy-scripts/oracle-bone-script-characters/.

[2] See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Seal script’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 25 September 2016, 17:21 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Seal_script&oldid=741141214> [accessed 25 September 2016] and Wikipedia contributors, ‘Clerical script’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 8 August 2016, 13:06 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Clerical_script&oldid=733530270> [accessed 8 August 2016]

[3] While this unification came also with what is known as the great “Burning of Books” (213 BCE), it is believed that most of ancient Chinese literature was nonetheless preserved. Like any great destruction of literature and culture however, it’s never clear what was actually lost because we simply don’t know what we don’t know. Standard academic scholarship today believes that most of the “important” works from classical Chinese antiquity were preserved but again, it’s not clear what was actually lost other than the fact that we know that a large scale destruction of ancient, non “Qin”, literature did in fact occur.

[4] Referred to in Pinyin as wényán wén, meaning “literary language writing”.

[5] See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Classical Chinese’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 27 June 2016, 08:32 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Classical_Chinese&oldid=727190919> [accessed 11 September 2016]

[6] The Chinese system of writing also has the further advantage that the same word, phrase or meaning can be represented by the same Chinese character or set of characters and be read and understood by the speakers of various languages that the system of writing supports. In other words, the same word written in Chinese characters can be spoken in many different languages, while at the same time still be symbolized and represented by just one set of characters, i.e. one Chinese “word”.

[7] To even further complicate matters, given the gaps in the historical record, many of the symbols in the core part of the Yìjīng for example, do not necessarily have counterparts in the ancient language itself that we know of, at least none that have been discovered as of yet. So in other words, while the symbols which are associated with the various hexagrams in the Yìjīng are believed to be very old, there are very few if any counterpart symbols that are found in Oracle or Bronze script inscriptions that are extant that tell us what the origins of these symbols are or what they might have actually meant, beyond their association with the hexagram itself within the Yìjīng.

[8] As an example of how a Chinese character evolved from antiquity into Classical or Traditional Chinese, take for example the word “rén”, or 仁 in Traditional Chinese. Perhaps the best translation of this symbol or “word”, one which carries much significance within the Confucian philosophical milieu from which it emerged, is “benevolence”. But it can just as easily, and accurately, be transliterated as “humanity,” “humaneness,” “goodness,” or even “love”. If we look at the individual Chinese characters that make up the “word” though, i.e. understanding its etymology so to speak, we can come to an even better understanding of its true meaning, what the word. One interpretation for example of the origin of “仁” is that it is the character that represents “man” or “human being”, i.e. “人”, combined with that of the Chinese character for “two”, or “二”, i.e. denoting the proper way in which people should interact or behave toward each other. Also interestingly, he two words represented by “人” and “仁”, are actually pronounced the same in spoken Chinese, evidence for the permeation of Confucian thought throughout China where “man” and “humanity” have become virtually, if not linguistically, synonymous. This is a very good example of how the unique Chinese form of writing, while much more complex and harder to learn than the written alphabetic (Roman/Latin) languages we have become accustomed to in the West, can actually support a much deeper and sophisticated meaning to words and phrases than their Western counterparts. If we contrast this with the modern notion of “virtue” for example, a word that carries similar connotations and meaning to the Chinese word “rén”, we find that the word is derived directly from the Latin word for man, or “vir’, and is the most common translation of the Greek (Aristotelean) notion of arête, which is sometimes translated as “excellence”, we not only have a direct modern English equivalent to which we can attach to the ancient Greek word, i.e. again arête, but given the very close relationship between the Roman/Latin cultures and the Greek, and the longstanding written translation tradition that exists from the Greek to the Latin and then from the Latin to modern Western European languages (and sometimes directly from the Greek to modern European languages), the “meaning” of the ancient word is much more clear to the Western mind, for in fact the intellectual and metaphysical worldview of the West is constructed upon these very intellectual and linguistic foundations as it were.

[9] For a very comprehensive review of these difficulties see a very recent entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy written by Henry Rosemont Jr. “Translating and Interpreting Chinese Philosophy”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2015 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), forthcoming URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2015/entries/chinese-translate-interpret/>.

[10] We have made every effort in this text to use the modern Pinyin Romanization formula for Chinese words or phrases but in some cases we use the old Wade-Giles terms as well, or at least in conjunction with, the Pinyin.

[11] The same can said of the lyric poetic traditions of the ancient Greeks attributed to Homer and Hesiod, the Vedas of the Indo-Aryans which was written in various forms of Brāhmī script (reflecting the ancient Sanskrit language), and the Avesta of the Indo-Iranians which was written in Avestan. All of these ancient texts reflect pre-historic oral traditions which were characterized by a lyric form of poetry as it were that was designed, at least with respect to the Vedas and parts of the Avesta at least, to be recited within the context of specific sacrificial and/or ceremonial worship and furthermore was intended to capture the precise pronunciation of specific words and verses which was required in order for the ceremonies to bear proper fruit. From a practical standpoint however, it is generally understood that it made it easier for the oral tradition to persist and be passed down from generation to generation if the language therein had a specific meter and/or cadence and rhythmic character, which in turn made the material much easier to memorize – an important characteristic of the transmission of these ancient texts before writing systems were even invented. This is why while academics and ancient historians typically date these ancient texts around the time when we believe and/or know they were compiled, i.e. actually written down, it’s also clear that the “content” of the texts, as well as many of the actual verses and passages that we find in the texts themselves, can be traced much further back in time – hence the wide range of dates typically attributed to ancient texts in the scholarly and academic literature.

[12]Lao-Tzu Te-Tao Ching. A new Translation Based on the Recently Discovered Ma-wang-tui Texts. Translated, with an introduction and commentary, by Robert G. Henricks. Ballantine Books, 1989. [Referring to textual discoveries made in 1973 at Ma-wang-tui where two copies of the Dàodé Jīng were found that that date back to the second century BCE, some five centuries older than other copies of the Tao Te Ching that were known at the time.]

[13] The Dàodé Jīng text that was discovered in the Guodian province (Hubei province) was written in a form of ancient Seal script on bamboo slips, three sets of them actually, referred to in the literature sometimes as the Guodian Dàodé Jīng or simply the Bamboo Slip Lǎozǐ (slips A, B and C) and can be reliably dated to the late 4th or early 3rd century BCE, at the end of the Warring States Period (4475-221 BCE) basically, and representing a textual tradition that is two centuries earlier than previously known extant versions of the Dàodé Jīng. The Bamboo strips were excavated just outside the ancient capital of the ancient Chinese state of Chu, which is incidentally where Lǎozǐ is believed to have been from.

[14] A Philosophical Translation Dàodé Jīng “Making Life Significant”. ‘Featuring the Recently Discovered Bamboo Texts. Translated and with commentary by Roger T. Ames and David L. Hall.’ Ballantine Book, 2003.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!