Muslim Philosophy: Muhammad, the Qur’an and Aristotle

Despite Charlie’s Jewish heritage, at least Jewish by blood, and his penchant for the less rigid and orthodox theological systems of the East, he knew little about Islam outside of his aversion for its fundamentalist interpretation which, along with its Jewish fundamentalist counterpart, was the source of so much conflict and political turmoil in the modern era, ironically enough in the very same region of the world where civilization first emerged some seven thousand years ago or so.

But he couldn’t properly explore the evolution of metaphysics and theology in Western civilization and its metamorphosis into science, an offshoot as it were of his mandated thesis surrounding theological cultural borrowing in the ancient world, without having some level of understanding of its development and evolution after the so-called fall of the Roman Empire through the Middle Ages, after which science clearly emerges as the dominant world view, eclipsing theology and religion which had dominated the intellectual landscape since the dawn of man. And it was clear that you couldn’t look at theological development during this time period without seeing it not only through the lens of Christianity, but also through Islam, the latter of which was a major force in the Western world not long after its introduction by its prophet Mohammad in the 7th century up until modern times. And interestingly enough, once Charlie started digging into this era of metaphysical and theological evolution from an Islamic perspective, he found that the early Muslim theologians and philosophers also leaned on Hellenic philosophy for their legitimacy and authority in much the same way that their Christian counterparts to the West had done some five centuries earlier, even going so far as to refer to Aristotle as the “First Teacher” in some contexts.

As the stability of the Roman Empire broke down in the 5th century, marked most notably by the sacking of Rome by the Visigoths in 410, a new center of influence and power emerges in the Eastern part of the Roman Empire with its capital in Byzantium, later renamed Constantinople and today called Istanbul in the modern nation of Turkey. The Byzantine Empire, or Eastern Roman Empire, as it came to be known by modern historians, was effectively an extension of the Roman Empire in the East after Rome collapses in the 4th century, although it reflected a much more Hellenic and Greek outlook than its Latin counterpart to the West. The state sponsored religion remained Christianity however, and this Empire persisted as a force in the Mediterranean and Near East for a thousand years or so until Constantinople fell to the invading Ottoman Turks in 1453.

As orthodox Christianity starts to mature and spread with the help of first the Roman and then Byzantine Empire, Islam is founded as a counter force by Muhammad (c. 570 – 632 CE) in the 7th century in what is now modern day Saudi Arabia, lying just South East of Constantinople and the center of Christianity. Islam in the coming centuries and even down through into modern times becomes a powerful force running parallel to and in many respects in reaction to Christianity in the Mediterranean, Middle East, and North Africa (and in present day of course throughout the world). Islam leans on the same Abrahamic heritage as does Judaism and Christianity, and yet at the same time it espouses the belief that although Jesus as well as Moses were in fact true prophets of God, or Allah, that their message had been altered and/or misinterpreted over time and that it was Islam, as revealed to Muhammad by Allah himself and as reflected in the Qur’an, is the one and only unadulterated version of truth and represents the final revelation of God in the modern era.

And We did certainly give Moses the Torah and followed up after him with messengers. And We gave Jesus, the son of Mary, clear proofs and supported him with the Pure Spirit. But is it [not] that every time a messenger came to you, [O Children of Israel], with what your souls did not desire, you were arrogant? And a party [of messengers] you denied and another party you killed.[1]

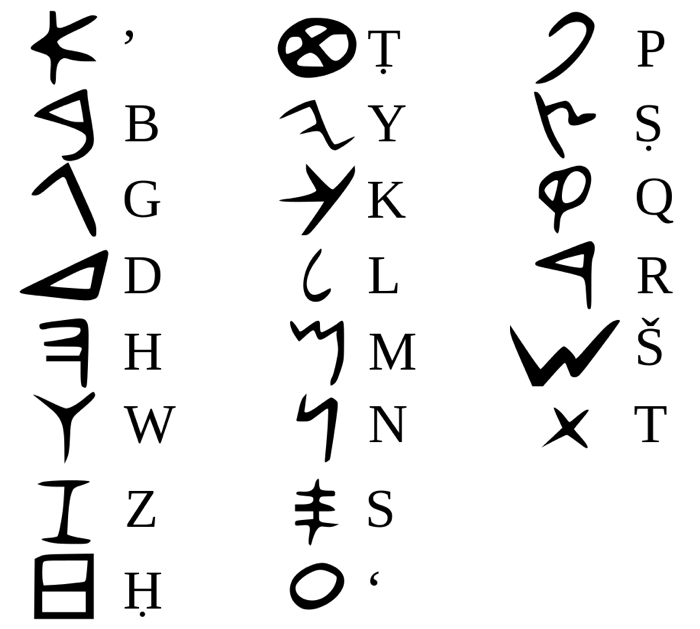

The word Islam in Arabic stems from the assimilation and integration of three letters/concepts in the Arabic language, “s-l-m”, the combination of which are taken together and denote “wholeness”, “safety” or “peace”. Within a religious context, Islam is the infinitive of a verb which can be loosely translated into English as something along the lines of “the voluntary submission to God’s will” and the word Muslim, which is what followers of Islam are referred to as of course, is the active participle of the same verb.[2] During the latter years of his life, Muhammad not only founded Islam and established the Muslim brotherhood, but he also became a renowned political leader and consolidated the various warring tribal forces of the Saudi Arabian peninsula, culminating toward the end of his life in the establishment of the Constitution of Medina in 622 CE which established the first Islamic state in history.

As the story goes it is said that the Qur’an, as transcribed by Mohammad’s followers shortly after his death, was revealed to Muhammad by the archangel Gabriel in a series of revelations starting from when he was around 40 years old up until the end of his life. The Qur’an, written in poetic Arabic, is composed of verses, or ayat, that make up 114 chapters, or Suras, which are classified either as Meccan or Medinan depending upon the place and time of their claimed revelation. The Qur’an, along with the biographical and historical material associated with the life of Muhammad in what is referred to as Al-sira, or simply sira, along with the hadith, which are sayings and phrases attributed to Muhammad or his followers that have been handed down over the centuries in either oral or written form, in toto form the basis of Islamic thought and religion as it is practiced today.[3]

In Islam, the concept of monotheism is referred to as the tawhid, a word reflecting the singular, unique, and wholly integrated nature of the one true God, or Allah – wahid is the word for “one” in Arabic. Islamic monotheism can be viewed as a more pure form of monotheism relative to Christianity in that it, consistent with the Jewish tradition, does not teach the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, holding it to be a misunderstanding or misinterpretation of the inseparable and unified nature of the one true God, or Allah.

Although Islam references and acknowledges the prophets of the Jews as documented in the Old Testament, and even acknowledges the Torah and Gospel as revealed scripture[4], it does not distinguish Jesus as the son of God and as the one and only messiah as Christianity does, and in the Qur’an its message is quite clear that Christianity and Judaism, as it was practiced by the followers of the respective faiths as viewed through the eyes of Muhammad, had become watered down and diluted and no longer paths to righteousness or salvation and unless a believer was to take up the message of Islam, then they would be subject to eternal damnation upon Last Judgment, just as the Christians believed was the fate of all those who did not take shelter in Jesus as their savior.

Islam teaches that the Jewish and Christian religions, like other pagan or polytheistic religious practitioners, have lost their way, and that despite their shared lineage and history with Muslims, have had their faith tarnished and jaded over the centuries since their scripture had been revealed to their respective prophets – the Torah of Moses and the Gospel of Jesus – and that the world was in need of a new, freshly revealed and interpreted faith in order to save mankind from evil.

The Jews say “The Christians have nothing [true] to stand on,” and the Christians say, “The Jews have nothing to stand on,” although they [both] recite the Scripture. Thus the polytheists speak the same as their words. But Allah will judge between them on the Day of Resurrection concerning that over which they used to differ.[5]

From a more academic perspective, the Qur’an is believed to have been transcribed some 20 years or so after Muhammad’s death by one of his followers in order to ensure a single source of the scripture for all Muslims and discourage fragmentation among the Muslim community. Islam over the centuries has remained largely unified in its basic theology and content of its scripture, much more so than Christianity in fact, and it is the adherence and belief of different sets and interpretations of hadith, which are variously attributed to Muhammad by different sects of Islam, rather than different interpretations of the Qur’an, that are the source of the various flavors of Islam present today; namely Sunni, Shi’a and Ibadi.

Consistent with all orthodox religious believers of scripture across all major faiths, fundamentalist Muslims believe that the precise words and verses that exist in the Qur’an were directly revealed to Muhammad by Allah himself and furthermore Muslims believe, perhaps more so than their religious counterparts, that this transcription of revelation was kept word for word into the Arabic, hence the significance of the contents and verses of the Qur’an and their recitation to the devout Muslim community. Whether or not this transcription was in fact as accurate and unadulterated as the orthodox Muslims believe, and of course whether or not one believes that the Qur’an represents a direct divine revelation at all, is, like all religious doctrines, a matter of faith. However, it is fairly safe to assume as most modern scholars do that the organization of the sayings of the Qur’an into verses and chapters (Suras) was a later invention of the author/editor of the Qur’an rather than a construct of Muhammad himself, speaking to the relevance and importance of written transcription upon the Islamic faith that is characteristic of all major religions no matter what their place in history is.

As Christianity incorporates the Jewish tradition, Islam also looks to the same historical and mythical narrative as encapsulated in the Old Testament to establish its own legitimacy and authority. Islam however, as juxtaposed with Judaism, accepts the message of Jesus as captured in the Gospels as revelatory as well, although it does not go so far as to accept him as the Son of God or of course as the only means of salvation as Christianity preaches.

The Qur’an contains many references to the long line of Jewish prophets as well as Jesus, and even contains reference to Old Testament characters and stories such as Adam and Eve, Noah and the flood, etc., assuming in fact that the reader (or listener/student as the case may be) is already quite familiar with Jewish and Christian lore. The Qur’an relays some of the same Old Testament stories and myths within its own unique and colloquial narrative but adds a slightly different perspective, constantly reinforcing the notion that the message as it was revealed to the Old Testament prophets and to Jesus was true and legitimate, but that it had been so garbled by subsequent practitioners and followers that it was in need of a new and revised revelation, i.e. Islam. Even more so Christianity perhaps, Islam looks to its scripture the Qur’an and the life of its prophet Muhammad as the one and only means to salvation, resting on the revealed nature of its scripture along with its breadth and scope of social and legal tenets as the basis for all spiritual life and ethical conduct and ultimately as the source of salvation.

What Charlie found interesting however as he learned more about the development of Islam in the centuries that followed the death of Muhammad and the expansion of the Islamic empire throughout the Middle East, was that some of the most prolific and influential subsequent interpreters of the Islamic faith (falsafa as they were called following the Greek tradition of philosophy, note the phonetic similarity between the two words) looked to Hellenic philosophy to legitimatize and establish a more sound metaphysical foundation for their faith, just as the early Judeo-Christian theologians had done, with marked influence by the works of Aristotle but also Plato, Euclid and others as well.

During the first few centuries after Mohammad’s death in 632 CE and the subsequent proliferation of Islam in the Mediterranean and Near East via the Muslim conquests, many of the Greek philosophic works were translated into Arabic. The Arabs used the word falsafa as the Arabic translation of the Greek word “philosopher”, and as these classic Greek works were translated into Arabic and incorporated into the Muslim theological traditions via commentaries and teachings, Greek philosophical constructs were integrated into the Muslim theological tradition in much the same way as had occurred in the Jewish and Christian theological traditions some four or five centuries earlier. These works and their associated commentaries and interpretations by Muslim theologians were categorized as Islamic wisdom, or hikmah in Arabic, a word that is used in the Qur’an associated not only with the teachings of the Qur’an itself, but also as an epithet of Allah, “the Wise”, establishing the connection between the wisdom of the Greek philosophic tradition with the teachings of the Islamic faith.

Our Lord, and send among them a messenger from themselves who will recite to them Your verses and teach them the Book and wisdom and purify them. Indeed, You are the Exalted in Might, the Wise.[6]

The Arabic/Islamic respect for the Greek philosophical tradition begins very early in the history of Islam, and it is documented that as early as the reign of the Abbasid Caliph Al-Ma’mun (786-833 CE), significant efforts were made to collect Greek philosophic manuscripts from the Byzantine Empire and have them translated into Arabic by scholars in Bagdad, establishing an academic tradition and sphere of influence in the Muslim world that was akin to Hellenic Alexandria in antiquity. As part of this 9th century movement in Bagdad under the Abbasid Caliphs[7] to translate Greek philosophic works into Arabic, Abu Yusuf Ya’qub ibn Ishaq al-Kindi, known in the West as Al-Kindi (801-873), emerges as the first and perhaps foremost of the Muslim falsafa. Bagdad during this time is sometimes referred to as the “house of wisdom”, or bayt al-hikma in Arabic during this early period of Muslim philosophical development, again speaking to the high position that the Arabic / Muslim community had for theological and philosophical thought in general, which at that time was very closely tied to – as it was with the Greeks before them – what we would now consider to be the sciences, both moral and ethical, as well as physical.

Although much of his work is lost, he is remembered and revered as the leader of the first major effort by the Muslim Empire to translate Greek philosophic works into Arabic and thereby comes to be known as the father of Islamic philosophy. Some of the most lasting and influential works translated under the name Al-Kindi are Aristotle’s Metaphysics, The Enneads (IV-VI) of Plotinus, the Elements of Theology by Proclus, the Timaeus of Plato as well as many other assorted works by Aristotle and other less well known Greek philosophers. Although it is believed that Al-Kindi himself did not know Greek and therefore did not translate any of the texts himself, it is believed that he made corrections and provided commentary to the translations that are attributed to him and his team of scholars and academics.

Following the Greek philosophic tradition, and speaking to Al-Kindi’s being a philosopher (falsafa) in the true Greek sense of the word as a lover of wisdom, Al-Kindi authored works on topics as broad ranging as medicine, astronomy, and mathematics alongside his theological and metaphysical works, and is attributed by later historians to be skilled in the arts of the not only the Greeks, but the Persians and Hindus as well[8]. He is believed to have been the author of works such as On First Philosophy, for which is perhaps best known, an ontological work called On the Definitions of Things and Their Descriptions which was subsequently superseded by Avicenna’s Book of Definitions in the 11th century, a treatise on ethics entitled On the Art of Averting Sorrows which bears many resemblances to Greek Stoicism[9], and other works entitled On the Unity of God and the Limitation of the Body of the World, and Quantity of the Books of Aristotle and What is Required for the Acquisition of Philosophy, displaying a marked Aristotelian influence on his work, albeit from a creationist perspective, both characteristics which were inherited and fleshed out by subsequent Islamic falsafa.

With his body of work and efforts, Al-Kindi is attributed to having not only making mainstream Greek philosophy available to the Arabic world for the first time, but also establishing the first semantic bridge between Greek and Arabic philosophy and establishing the importance and relevance of specifically Aristotelian doctrine in the Islamic philosophical tradition, a somewhat unique and distinctive characteristic relative to Christian theological development which was influenced much more by Neo-Platonic thought and principles that the more logical and metaphysical Aristotle.

Further assimilation of Greek philosophy into the Islamic philosophical tradition is attributed to Al-Farabi (c 872-951 CE), one of the most renowned and influential of the Muslim philosophers whose influence extended beyond the Muslim world to the European philosophical community at large as well. Al-Farabi spent most of his life in Bagdad and along with his contributions to Muslim philosophy proper, also made significant contributions to the fields of logic, mathematics, music and psychology, following the tradition of the Greek philosophers as a true lover of wisdom in all its forms.

Al-Farabi is known in the Arabic community as the second teacher, or “second master”, Aristotle being known as the first teacher, speaking to the prestige within which not only Al-Farabi was held by subsequent Muslim philosophers and theologians, but also the respect given to Aristotle himself in the Muslim philosophical community despite his altogether Greek, and foreign, heritage from some 1500 years prior.

Al-Farabi most famous work is perhaps The Virtuous City, which despite being authored in a similar vein as Plato’s Republic in describing the characteristics of the ideal state and the role of the philosopher within it as well as being designed to be a critique of the political structure and establishment of his time, displays a much more monotheistic and Neo-Platonic view of the world than his Greek predecessors, espousing the belief of a single creative force in the universe which distinguishes Al-Farabi’s philosophy from his Greek predecessors and even his Neo-Platonic predecessors in his monism.

In general, Al-Farabi’s philosophy/theology is a unique blend of Platonism and Aristotleanism, with emphasis on the unity of existence combined with a physical cosmology and world order that was based on practical astronomy derived from the work of the famous Greco-Roman Alexandrian astronomer Ptolemy. Al-Farabi’s emphasis is ultimately on the indescribable and ineffable first cause, displaying his characteristically Aristotelian and in turn Western influence, but he identifies this first cause, the primary mover, as indistinguishable or synonymous with God, or Allah, putting him in what might be considered an orthodox monotheistic Neo-Platonic tradition, diverging from the Neo-Platonists before him, which works he clearly had access to in Arabic, but spoke of the divine triad and emanation of the many from the one rather than a deterministic type world view which is more attributable to Aristotelian works.

Al-Farabi’s work, as Plato and Aristotle had focused on before him, also clearly dealt with socio-political matters, emphasizing the practical importance of philosophy and the role of the philosopher in society, not as the philosopher king necessarily, as Plato describes in his Republic, but as a harbinger and role model of moral and ethical standards and responsible for leading a life directed toward the realization of what he refers to as “true happiness”, a goal which he describes not just for the individual but as for the society as a whole, within which it is the role of the philosopher to lead and show the way by example, reminiscent to some extent of Stoicism in some respects, whilst at the same time leaning on the civic duty constructs that were so prominent in the works of Plato and Aristotle.

The next Muslim philosopher whose life and works influences not only subsequent Muslim philosophers but also Medieval philosophy in general is Ibn Sina, or as he is known in the West Avicenna (c 980 – 1037 CE)[10]. Avicenna followed Al-Farabi by a century or so and published many works on topics ranging from philosophy, astronomy, mathematics, logic, theology and medicine that were influential on Arabic thought, scientific and medical practices in the Arabic world in his day and thereafter, philosophical and otherwise making him one of the best known of the historical Muslim philosophers.

Perhaps his best-known philosophical treatise is his Kitab al-Shifa’, sometime referred to simply as al-Shifa’, or in the West known as the Book of Healing, which was written early in his life and partially in exile (reflecting the revolutionary aspects of some of his beliefs and writings), covers topics as broad as the not only theology and metaphysics, the soul and the afterlife, but also on mathematics and logic, carrying the tradition of Arabic falsafa forward to no small degree. His works on logic that he is perhaps best known for are al-Mantig, translated as The Propositional Logic of Ibn Sina, and a commentary on Aristotle’s Prior Analytics which forms part of al-Shifa’ entitled al-Isharat wa-‘l-tanbihat or Remarks and Admonitions. He is also known by later biographers to have published works many other short works on metaphysics and theology, medicine, philology, zoology as well as poetry, much of which is unfortunately lost.

From a philosophical standpoint, Avicenna is clearly heavily influenced by his Greek and now Muslim predecessors in his upholding of the primary role of the faculties of human Reason and the Intellect as the primary tools, or guides, to God, or Allah. He creates a fairly comprehensive theory of knowledge which underpins his philosophy which bears resemblance to Plato’s Theory of Forms to some degree but to Avicenna, Allah is equivalent to pure unadulterated Intellect which represents a somewhat unique twist on the philosophy and metaphysics of his predecessors, both in the Muslim philosophical tradition as well as the Hellenic one, although he still leans on the equivalence between Allah and Aristotle’s first cause, consistent with his Muslim philosophical predecessors, but with a marked Islamic focus on the eternity of the soul and its battle between good and evil which in turn leads to reward or punishment, themes that are prevalent in the Qur’an.

Ibn Rushd (1126-1198), know to us in the West as Averroes is known for the innovative creation of a markedly pure Aristotelian doctrine which came to be know as Averroism which as it turned out was not nearly as influential in the Islamic world as it was in Medieval, primarily Judeo-Christian Europe. His influence from a theological and philosophical standpoint can most notably seen in the development of early scholasticism, which in turn heavily influenced the education system in Europe through the Middle Ages and even into the Renaissance.

He wrote many commentaries on Aristotle’s works including Physics, Metaphysics, Book of the Soul, and On the Heavens and Posterior Analytics. His classic work Fasl al-maqal, or Decisive Treatise On the Harmony of Religion and Philosophy went one step further from a philosophical standpoint than his Muslim philosophical predecessors and not only established the ultimate compatibility of philosophy and Islam, but also, much to the chagrin of his orthodox Islamic brethren, argued that philosophy in its pure quest for knowledge represented a more pure and direct path to salvation and pointed out the role of politics and power within the context of religious interpretation, emphasizing the important role of language citing how words can be understood to mean different things to different people in different socio-political contexts.

Irrespective of the clear and powerful impact of Muslim philosophy in the Middle Ages not only on Islam but also on Judeo-Christian theological development in the West, this Arabic movement facilitated and in some cases was the only source of the availability of the Greek philosophical texts the now predominantly Christian and Islamic Western world in the Mediterranean and Near East from the 7th through the 12th centuries and even down through modern times.

Orthodox Islam then, like Christianity and perhaps to a lesser extent Judaism before it given the age of its scripture, places emphasis on the literal interpretation of the Qur’an itself as revealed scripture before individual theological interpretation or individual realization – all questions and answers lay either in the Qur’an itself or in the hadith and sira that sprung Muhammad’s revelation. What has been altogether lost however, at least from Charlie’s perspective, was that there was clearly a socio-political motive embedded and integrated within the message of Muhammad which was reflected quite markedly in the Qur’an itself, more explicit and emphasized in fact than in its rival Jewish and Christian faiths to which the Qur’an repeatedly references as tainted and outdated paths to salvation, paths followed by the so-called unbelievers. The attempt is commendable, and surely the times and turmoil of the age of Muhammad in some sense demanded this broad theological and socio-political grounding, but scholars and interpreters of his “words”, be they people of Islamic faith or simply philosophers, must take into account the social, economic and spiritual plight of the peoples to which Islam originally resonated to truly understand his message.

The Qur’an’s use as a means to political ends and as a tool for social welfare is evidenced by the breadth of socio-political topics it covers, topics such as banking and trade, the role of war in society, women and marriage, and even man’s relationship to the environment. These views lay somewhat in contrast to the philosophy of the Greeks who are known for the grounding of morals and ethics into a rational and intellectual framework rather than a religious one based upon the quest for salvation or inversely the avoidance of eternal damnation. The Greeks however, a tradition followed and emphasized by Averroes, believed not only that philosophy and religion were ultimately compatible and complementary, but that it was the path of philosophy and the pursuit of knowledge that was in fact a more direct and unadulterated path toward liberation, in this life or the next, given in no small measure due its independence from political motive which undoubtedly has historically, and continues to this day, to taint organized religion[11].

Over the centuries following Muhammad’s death, Islamic influence spread throughout the Middle East, North Africa and into Central Asia via the Muslim Conquests, an age of conquest and proliferation of the Islamic faith that Muhammad himself started on the Arabian peninsula, creating a sphere of influence by the 8th century CE that rivaled even the Roman Empire at its height. From the start, Islam was not only a religious system that outlined how to worship the one true God, i.e. Allah, and that idolatry and paganism was to be shunned, but it also prescribed a system of law and a way of life in a very detailed and explicit way such that political as well as religious harmony could be achieved. Such was the origin of the great faith of Islam that has been handed down to us over the centuries.

[1] Qur’an Sura 2, Al-Baqara, verse 87. From http://quran.com/2.

[2] The Hebrew word Shalom and the Arabic word Salam, which both mean “peace” in their respective tongues, share a similar root to that of “Islam”. Note both Arabic and Hebrew are Central Semitic languages so share some of the same common word etymologies and meanings.

[3] The Qur’an, Sira and Hadith are roughly analogous to the concepts of the Tanakh, Torah, and Talmud in the Judaic tradition respectively which make up not only the revealed scripture of the Jews (the Torah), but also the rabbinical and oral teachings handed down over the ages after Moses via the Rabbinical tradition, i.e. the Tanakh and Talmud.

[4] “He has sent down upon you, [O Muhammad], the Book in truth, confirming what was before it. And He revealed the Torah and the Gospel”; Qur’an Sura 3, Al-Imran, verse 3.

[5] Qur’an Sura 2, Al-Baqara, verse 113. From http://quran.com/2.

[6] Qur’an 2:129. Translation taken from quran.com/2.

[7] Caliph being the term Arabs user for their rulers some centuries after Muhammad’s death. It means “successor”, “lieutenant” or “substitute” in Arabic, referring to the connection between rulers and the lineage back to Muhammad.

[8] See http://www.muslimphilosophy.com/ip/rep/H029.htm

[9] Authenticity of this work to Al-Kindi is questioned by some later historians.

[10] Latin translations of Avicenna’s works influenced many Christian philosophers, most notably Thomas Aquinas.

[11] Note the philosophical parallels that can be drawn between the role of the intellect as the means toward liberation in Muslim philosophy which is such a prevalent theme in Averroism, its precursors in Greek philosophy as can be found in the philosophy attributed to Anaxagoras which can be found inherent in the cosmology implied or inferred from the Derveni papyrus, and the importance of knowledge, or jnana, in Vedanta, most prominently seen in the path of Jnana Yoga as interpreted by the more modern Swami Vivekananda (1863-1902).

May I suggest the following book;

How Early Muslim Scholars Assimilated Aristotle and Made Iran the Intellectual Center of the Islamic World: A Study of Falsafah

Author: Farshad Sadri

Foreword: Carl R. Hasler

Hardcover: 217 pages

Publisher: Edwin Mellen Pr (June 30, 2010)

ISBN-10: 0773437169

ISBN-13: 978-0773437166

This work demonstrates how falsafah (which linguistically refers to a group of commentaries by Muslim scholars associated with their readings of “The Corpus Aristotelicum”0 in Iran has been always closely linked with religion. It demonstrates that the blending of the new natural theology with Iranian culture created an intellectual climate that made Iran the center of falsafah in the Medieval world. The author begins this book by exploring the analytical arguments and methodologies presented as the subject of the first-philosophy (metaphysics) in the works of Aristotle (in particular “The Nicomachean Ethics” and “Rhetoric”). Then, he tells the tale of the Muslims’ progression as they came to own and expand upon Aristotle’s arguments and methodologies as a measure of their own sense of spirituality. Last, Sadri surveys the implications of that sense of spirituality as it is amalgamated within the Iranian culture and today’s Islamic Republic of Iran. The author’s aim is to present a different perspective of falsafah (as it is received by Muslims and assimilated within Iranian culture), while maintaining a sense that captures the texture of everyday life-experiences in today’s Islamic Republic of Iran. This work is thus about (contemporary) Iranian falsafah and how it remains faithful to its tradition (as falsafah has actually been integrated and practiced by Iranian scholars for the last eleven centuries). It is a tradition that has taken on the task of understanding and projecting a sense of order upon the multiplicity of forms, ideas, examples, and images that have passed through Iran from East and West; it is a story that has gathered, sheltered, and introduced a style and order of Iranian Islamic (Shi’at) falsafah.

Reviews

“While Sadri’s monograph is written in an engaging, quasi-autobiographical style, still it is rich in philosophical exposition and insight coupled with a clearly developed explication of Islamic religious/philosophical thought in the Islamic Republic of Iran. In turn this is used to explain Iranian culture as it can be understood in contemporary analysis.” – Prof. Carl R. Hasler, Collin College

“The interdisciplinary approach allows [the author] to introduce a chronicle of his people that encompasses the dynamic growth of the intellectual and religious thought in the Middle East. A thoughtful study for scholars of comparative religion, Sadri juxtaposes Medieval Islam with Medieval Christianity, showing the philosophical foundations that distinguish these two contemporary religions.” – Prof. Linda Deaver, Kaplan University

“Taking as his point of departure the fate of Aristotle’s corpus in medieval Christianity and in medieval Islam, Sadri offers a masterful account of how the current status of Western and Iranian identity can be read through the palimpsest of a philosophical/religious recovery of Aristotle’s practical philosophy.” – Prof. Charles Bambach, University of Texas, Dallas

Table of Contents

Foreword

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1. Commentaries on Aristotle

2. Commentaries on Aristotle and Islam

3. Commentaries on Islam

4. Commentaries on Islam and Iran

5. Commentaries on Iran

Endnotes

Bibliography

Index

Subject Areas: Cultural Studies, Islamic Studies, Philosophy

Thank you. I will.

interesting. thank you for the recommendation.

Thank you for your concise yet comprehensive explanation of Islamic history as it is intertwined with Aristotlianism. Just what I was looking for. This was even the first result in my Google search for those two keyword subjects so many others must fins this information useful too. Thanks again for your work.

Glad you find it useful. The roots of Muslim (Arabic really) philosophy with the Greeks I find fascinating – first from pure philosophical and theological perspective, Islamic monotheism to Aristotle’s first mover, and then second in connection to this modern East-West divide when in fact when looked at more closely, and intellectual, the history is almost direct linked.