Roman Cosmogony: The Metamorphoses of Ovid

When trying to ascertain the belief systems of the ancients, and specifically as related to their views on cosmogony and theogony, one is apt to conclude that anything written by the Latin/Romans can add nothing to the historical record of value – outside of reflecting the beliefs of the Latin/Romans themselves whose culture is renowned to be primarily, at least from an intellectual and theological perspective, to be a simple borrowing and renaming of that of the Greeks who were their predecessors to the East and whose culture and peoples the Romans conquered and assimilated through various conquests from the 3rd century BCE until the classic “Fall” of the (Western) Roman Empire in 476 CE.

Figure 9: Roman Empire at its greatest extent under emperor Trajan, 117 CE.[1]

Figure 9: Roman Empire at its greatest extent under emperor Trajan, 117 CE.[1]

The Romans were a civilization that clearly borrowed from its predecessors in many respects, their geographic boundaries at their height spreading to the realm of the Persians to the Near East, the Egyptians to the South and of course the Greeks and Macedonians which were their neighbors in the Mediterranean. They clearly borrowed much of their culture and intellectual tradition, and underlying mythos, from the Greeks no doubt. For example, as most of us know almost all of the Roman gods have direct Greek counterparts – Zeus to Juno, Poseidon to Neptune, Aphrodite to Venus, etc. But they did however of course have their own form of expression and writing, i.e. Latin, which is the direct predecessor to our modern European languages and is the alphabet we still use in the West today so clearly their influence upon the West cannot be denied. Additionally, Roman culture did produce the likes of Cicero and Marcus Aurelius, each influential philosophers and intellectuals in their own right, so we can’t altogether dismiss the Romans as conquerors, developers of state craft and military prowess necessarily either.

Even if we further presume that even if the Romans made some intellectual and philosophical contributions to Western thought, they produced no unique contributions to the domain of theology or mythology per se, collectively mythos, denying the heritage of say the Neo-Platonic tradition that although a product of the Roman/Byzantine empire nonetheless still evolves from a classically Hellenic, and Greek influence. We do however, know the Romans as being responsible for the widespread adoption of Christianity however, even if it is after centuries of brutal persecution initially until it’s basically adopted as the official religion of the Roman Empire at the end of the 4th century CE.[2]

The problem with this fairly simplistic and perhaps even prejudicial view of the Romans is that when one actually reads their classic mythological narrative, i.e. Ovid’s Metamorphoses, at least from a theo-philosophical perspective, one comes to altogether different conclusion entirely. That is to say, the Metamorphoses, and the Latin/Roman mythos which it has come to represent, does contain some very unique elements to it that do add to the theo-philosophical tradition in antiquity. If nothing else, perhaps it can be said that this work is one of the most influential and lasting epic narratives that has ever been produced in the West, rivaling the Iliad and the Odyssey in terms of notoriety and lasting influence which in and of itself makes a case for it to be analyzed on par with some of the other ancient theogonies such as Hesiod’s Theogony or the Enûma Elišs of the Sumer-Babylonians. Also, it’s fair to say that even if there is no unique content or independent value of the work itself, it does however reflect the mythos of our direct cultural predecessor and in this respect alone is worthy of consideration and analysis.

Ovid’s’ Metamorphoses then, if nothing else (and we will argue that it is much more) represents the pinnacle and synthesis of centuries of theo-philosophical and mythological narratives throughout the Mediterranean in antiquity. In other words, it is with Ovid that we find the most modern and developed interpretation of ancient myth as it was understood by the ancient peoples of the Mediterranean – peoples which included the Greeks, the Macedonians, the Sumer-Babylonians, the Egyptians and the Persians to name just a few of the major civilizations that came under Roman influence during the period of Roman Imperialism, a period which Ovid is born into and writes under.

Ovid, or Publius Ovidius Naso, was born in 43 BCE just to the East of Rome and died in exile on the coast of the Black Sea in 17/18 CE at the age of around 60. Ovid wrote his poetry, his earlier work having to do with the art of love, during the reign of Caesar Augustus, the founder of the Roman Empire and its first Emperor.[3] Augustus ruled over a vast kingdom in the area of the Mediterranean that covered almost all of modern Western Europe, North Africa and Egypt, classical Greece and Macedonia of course, as well as Near Eastern lands that were formerly under Persian rule. Augustus exiled Ovid to the Black Sea in 8 CE, just after the completion of his most famed work, the Metamorphoses, one of the richest and most expansive sources of Greek (and in turn Roman) mythology written in Latin in hexameter verse, the lingua franca so to speak of classic epic lyric poetry as had been established by the likes of Hesiod and Homer before him.

Ovid was well educated and of nobility, having been trained in the art of law and rhetoric in his youth. He was of enough noble and aristocratic birth for example to hold various minor legal and judicial public offices in Rome before resigning to pursue poetry as a young adult somewhere in his late teens or early twenties. He is known to have travelled extensively as well, visiting places throughout the Roman Empire such as Athens, the Near East/Asia Minor, as well as Sicily and it was no doubt through this knowledge, along with his teachings in the classics, from which he came to author his most ambitious and lasting work.[4]

The Metamorphoses contains 15 books and covers over 250 myths, starting with the creation of the world, the first few generations of gods and goddesses and then in turn covering many of the popular myths that we have come to associate with Greco-Roman civilization – Jason and the Argonauts, the myth of the Minotaur, the story of Daedalus and Icarus, the deeds of Hercules, etc. The work concludes with the history and mythology of the establishment of Rome, interwoven interestingly with material on Pythagorean philosophy, culminating with the reign and deification of Julius Caesar, establishing the work not just as a poetic narrative but as a historical narrative as well, connecting the mythological with the historical and political as most other ancient works of its kind. From this perspective the impetus of the work could be seen somewhat in the same light as the Enûma Eliš and some of the Egyptian cosmological narratives, establishing the connection of the ruling class, or Roman Emperor in this case, to the reign of the gods and the birth of the universe. Regardless there was something about Ovid’s work that concerned Augustus, hence his exile which remained in effect till the end of his life.

Ovid starts with not only the full content and purpose of the work, but also with the basic cosmogonic narrative that has a more theo-philosophical bent than the classic theogonic works that we are accustomed to seeing from this era in antiquity. From the opening verse we find:

Of bodies chang’d to various forms, I sing:

Ye Gods, from whom these miracles did spring,

Inspire my numbers with coelestial heat;

‘Till I my long laborious work compleat:

And add perpetual tenour to my rhimes,

Deduc’d from Nature’s birth, to Caesar’s times.

Before the seas, and this terrestrial ball,

And Heav’n’s high canopy, that covers all,

One was the face of Nature; if a face:

Rather a rude and indigested mass:

A lifeless lump, unfashion’d, and unfram’d,

Of jarring seeds; and justly Chaos nam’d.

No sun was lighted up, the world to view;

No moon did yet her blunted horns renew:

Nor yet was Earth suspended in the sky,

Nor pois’d, did on her own foundations lye:

Nor seas about the shores their arms had thrown;

But earth, and air, and water, were in one.

Thus air was void of light, and earth unstable,

And water’s dark abyss unnavigable.

No certain form on any was imprest;

All were confus’d, and each disturb’d the rest.

For hot and cold were in one body fixt;

And soft with hard, and light with heavy mixt.[5]

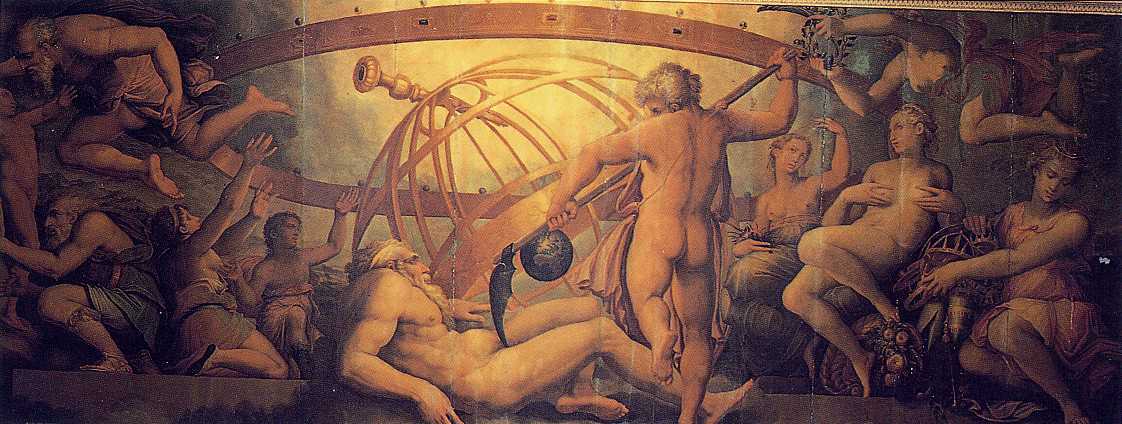

We see clearly here the notion of order out of Chaos, emerging out of a watery abyss of sorts, consistent not only with Hesiod’s account of creation which starts with Chaos, but also with the Egyptian and Sumer-Babylonian creation mythos which starts with this watery abyss from which the universe emerges. Ovid still nonetheless establishes the anthropomorphic basis for the creation of the various gods and goddesses – the theogonical narrative – which sets the stage for the various transformations and mythical accounts of the gods and heroes of the golden age of man that represent the main storyline of Ovid’s epic history of the world up until the present, i.e. the reign of Augustus.

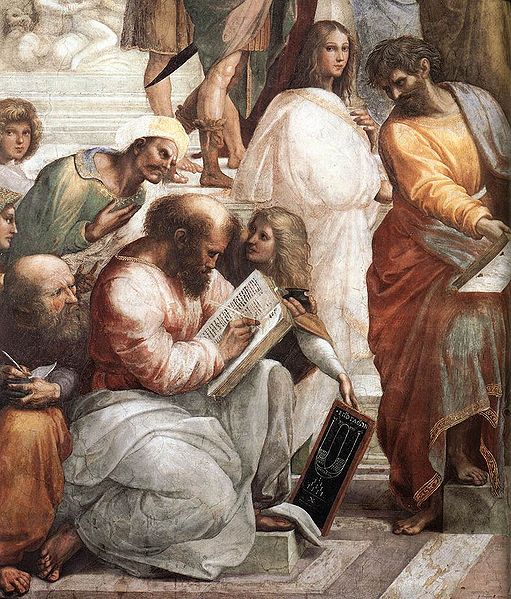

So while still have the immortal Chaos sitting at the pillar of creation, Time itself representing the “beginning” of the cosmos, we also have a much more “naturalist” creation mythos presented by Ovid, the universe emerging from the interplay and coalescence of opposing forces such as darkness and light, cold and heat, soft and hard that are reminiscent of the cosmogonic narratives of the Far East (i.e. China). What is also striking about this introduction, and is also very reminiscent of the theo-philosophical systems of the Far East, is its primary focus on change itself, i.e. metamorphosis, as the overarching theme of the work, the underlying philosophy and theme of the work as a whole as it were. Hence the title Metamorphoses and hence the inclusion toward the end of the work of the an explanation, and source, of this underlying philosophy which he attributes to Pythagoras.

Ovid then goes on to outline the basic building blocks, i.e. the elements, of creation – earth, air, fire and water – from which the Earth and Heavens and their various features are formed. The emphasis in this creation mythos shifts slightly from its predecessors from a focus on theogony – the creation of the generation of gods with their respective male and female attributes and counterparts and their ensuing conflict and quest for dominance – to the creation of the underlying fabric of the natural world out of these basic “natural” elements, betraying a more Hellenic theo-philosophical influence to his work which should not be altogether surprising given the intellectual context within which Ovid writes.

But God, or Nature, while they thus contend,

To these intestine discords put an end:

Then earth from air, and seas from earth were driv’n,

And grosser air sunk from aetherial Heav’n.

Thus disembroil’d, they take their proper place;

The next of kin, contiguously embrace;

And foes are sunder’d, by a larger space.

The force of fire ascended first on high,

And took its dwelling in the vaulted sky:

Then air succeeds, in lightness next to fire;

Whose atoms from unactive earth retire.

Earth sinks beneath, and draws a num’rous throng

Of pondrous, thick, unwieldy seeds along.

About her coasts, unruly waters roar;

And rising, on a ridge, insult the shore.

Thus when the God, whatever God was he,

Had form’d the whole, and made the parts agree,

That no unequal portions might be found,

He moulded Earth into a spacious round:

Then with a breath, he gave the winds to blow;

And bad the congregated waters flow.

He adds the running springs, and standing lakes;

And bounding banks for winding rivers makes.

Some part, in Earth are swallow’d up, the most

In ample oceans, disembogu’d, are lost.

He shades the woods, the vallies he restrains

With rocky mountains, and extends the plains.[6]

Outside of the flowing verse within which Ovid outlines this creation, it should strike the reader that while there remains a slight hint of skepticism about the notion of the existence of a Creator God (“whatever God was he”), akin to the “likely story” outlined in Plato’s Timaeus which Ovid no doubt was intimately familiar with, this Creator (Plato’s Demiurge) is nonetheless front and center in the role of forming and shaping the world. This synthesis of Hellenic mythos and philosophy is a unique characteristic of the work itself in fact, and in many respects foreshadows, and perhaps even plants some of the seeds, of the ensuing theo-philosophical revolution that is to take place quite soon thereafter, within the boundaries of the Roman Empire, stemming from the life and teachings of the Hebrew Jesus of Nazareth which over the next few centuries evolves into what we know today as Christianity.

Ovid continues his creation narrative with the final act of creation as it were, the creation of mankind, which contains many motifs and storylines that are reminiscent of the Hebrew creation story attributed to Moses (i.e. Genesis), as heaven is split and separated from the Earth, the various animals and beasts are created to fill the world, and mankind is formed as the last act of creation, bearing a special place in the halls of God’s creation as a direct descendant of the Creator himself.

Scarce had the Pow’r distinguish’d these, when streight

The stars, no longer overlaid with weight,

Exert their heads, from underneath the mass;

And upward shoot, and kindle as they pass,

And with diffusive light adorn their heav’nly place.

Then, every void of Nature to supply,

With forms of Gods he fills the vacant sky:

New herds of beasts he sends, the plains to share:

New colonies of birds, to people air:

And to their oozy beds, the finny fish repair.A creature of a more exalted kind

Was wanting yet, and then was Man design’d:

Conscious of thought, of more capacious breast,

For empire form’d, and fit to rule the rest:

Whether with particles of heav’nly fire

The God of Nature did his soul inspire,

Or Earth, but new divided from the sky,

And, pliant, still retain’d th’ aetherial energy:

Which wise Prometheus temper’d into paste,

And, mixt with living streams, the godlike image cast.Thus, while the mute creation downward bend

Their sight, and to their earthly mother tend,

Man looks aloft; and with erected eyes

Beholds his own hereditary skies.

From such rude principles our form began;

And earth was metamorphos’d into Man. [7]

In analyzing Ovid’s account of creation then, we can clearly see a variety of themes and motifs from various other creation narratives from the other civilizations which dominated the Mediterranean and Near East and pre-dated the period of Roman Imperial expansion and cultural synthesis which Ovid’s work clearly reflects. He integrates all of these old creation stories into the Hellenic theo-philosophical and mythological tradition, creating an altogether unique creation narrative.

For example while we see a reference, albeit not necessarily a direct account, of the battle between the second and first generation of gods which plays such a prominent role in the Egyptian, Hellenic and Sumer-Babylonian mythos, Ovid’s account of this battle and the ultimate reign of Jupiter (Zeus) is de-emphasized, replaced by a more (Middle) Platonic narrative that still nonetheless retains the existence of the Greco-Roman pantheon from which not only much of his mythical narrative is based upon, but also in fact to which he eventually connects Julius Caesar and Augustus as divine descendants to in the closing Books of the work.

We also see here in Ovid’s creation account mankind being called out as having a special place in “God’s” creation, being formed out of Earth as it were, synthesizing no doubt the notion of Plato’s Demiurge with the Hebrew notion of the one true God, i.e. Yahweh. This account is followed by a fairly lengthy description of this so-called “Golden Age” of man, which eventually evolves into subsequent morally degenerative ages which cause the gods to destroy their greatest creation via a Great Flood.[8] This narrative is all very reminiscent of the creation narrative in Genesis, where the Golden Age of Ovid corresponds to the creation of primordial man and woman in the Garden of Eden where death and suffering is not known to them. In this well-known account of their expulsion from the Garden, Adam is deceived by his woman partner, via the snake, to eat the “forbidden fruit” which angers Yahweh and gets them expelled from the Garden, and leads to Yahweh’s “curse” of man, due to his “original sin”, such that he must now toil the earth for sustenance and the woman must go through the pain of child bearing to rear children.[9] Further along in this mythical-historical narrative in Genesis, Yahweh becomes disappointed with man given his moral and ethical degeneration, and just as in Ovid’s narrative, destroys all mankind via a Great Flood, saving only Noah due to his righteousness.[10] This Great Flood narrative with the destruction of all mankind and their subsequent regeneration as it were through the sole survivor of a single moral and righteous being selected by the gods, of course can also be found in the great ancient Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh as well, a tale which can be traced as far back in antiquity to the end of the second millennium BCE[11].

While the works of Hesiod and Manu pre-date Ovid’s work by centuries if not more, they do speak to the far reaching intellectual and mythical lore that Ovid clearly had access to, and ultimately synthesizes, into his work. It also perhaps speaks to the synthesis of Greco-Roman, or perhaps in a broader sense Mediterranean mythos, into the Hindu mythological tradition – or of course perhaps the existence of a mythological tradition that predates all these civilizations from which they all draw from as their source.

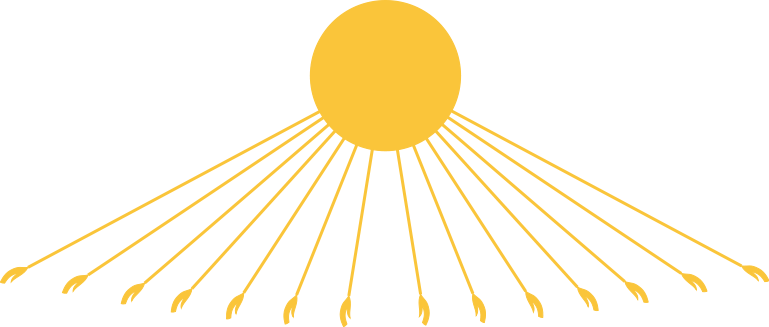

Furthermore, parallels have also been drawn between the Tree of Life which was planted in the center of the Garden of Eden and from which Adam and Eve ate from, and a tree motif that is found throughout ancient Mesopotamia and the Near East dating as far back as the 4th and 3rd millenniums BCE. This ancient Mesopotamian tree, the so called “Assyrian Tree of Life”, which although is not alluded or referred to in any of the written transcriptions or writings from ancient Mesopotamia, clearly has religious and mystical connotations given the context within which it has been found from an archeological perspective. One scholar has gone so far as to directly correlate this Assyrian tree motif, which plays such a prominent role in the Genesis Adam and Eve story, to the Kabbalistic Tree of Life, which of course represents the essence of the Jewish mystical tradition.[12]

Figure 10: Depiction of Assyrian Tree of Life[13]

Figure 10: Depiction of Assyrian Tree of Life[13]

All of this of course shows the clear corollaries and heavy cultural borrowing of many of the themes we find in Ovid’s creation narrative, which stems mostly of course from his Greek predecessor Hesiod, but also the connections between Ovid’s creation account and the Hebrew narrative in Genesis which contain Mesopotamian and Sumer-Babylonian themes and storylines which predate Genesis by centuries.

And lastly but certainly not least of all, the focus of Ovid’s work on change itself, i.e. Metamorphoses, and the parallels that can be drawn to the early Pre-Socratic philosophers such as Heraclitus and of course Pythagoras to which Ovid alludes to specifically as the source of his philosophy, can also be found as the basis for almost all of Chinese philosophy as reflected in the Chinese Classic of Changes, i.e. the Yìjīng, a work whose origins can be traced as far back as second millennium BCE China in the Far East. This interesting parallel begs some serious questions with respect to how old some of these basic philosophical principles are, i.e. the notion of change and impermanence as the essence of reality, and how is it that two cultures separated by thousands of miles with no known trade or cultural exchange until the 2nd or 3rd centuries CE could have adopted such similar theo-philosophical systems of belief.

[1]Image from Wikimedia commons from Wikipedia contributors, ‘History of the Roman Empire’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 17 September 2016, 14:58 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=History_of_the_Roman_Empire&oldid=739865396> [accessed 17 September 2016].

[2] In 313 CE, Emperor Constantine, aka Constantine the Great, issued along with his counterpart ruler to the East Licinius, the famed Edict of Milan, which decriminalized Christianity and effectively ended the persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. It wasn’t however until 380 CE with the Edict of Thessalonica, the so called Cunctus populous, i.e. “all the people”, that all Roman subjects were ordered to profess faith and adherence to the Christian faith as professed and governed by the bishops of Rome and Alexandria respectively.

[3] Augustus actually called himself Princeps Civitatis, or the “First Citizen of the State”, and after coming into power he established the constitutional framework – based upon the Senate, executive magistrates and legislative assemblies – which became known as the “Principate”. The reign of Augustus ushered in the Pax Romana, more than two centuries of relative peace throughout the Empire despite continuous battles fought for expansion on the Empire’s frontiers. See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Augustus’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 3 September 2016, 18:02 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Augustus&oldid=737568597> [accessed 18 September 2016].

[4] Wikipedia contributors, ‘Ovid’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 27 August 2016, 02:02 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ovid&oldid=736377368> [accessed 17 September 2016]

[5] Metamorphoses by Ovid. Translated into English verse under the direction of Sir Samuel Garth by John Dryden, Alexander Pope, Joseph Addison, William Congreve and other eminent hands. Published in 1826. Book I, “Creation of the World” translated by John Dryden. From http://classics.mit.edu/Ovid/metam.1.first.html

[6] Metamorphoses by Ovid. Translated into English verse under the direction of Sir Samuel Garth by John Dryden, Alexander Pope, Joseph Addison, William Congreve and other eminent hands. Published in 1826. Book I, “Creation of the World” translated by John Dryden. From http://classics.mit.edu/Ovid/metam.1.first.html

[7] Metamorphoses by Ovid. Translated into English verse under the direction of Sir Samuel Garth by John Dryden, Alexander Pope, Joseph Addison, William Congreve and other eminent hands. Published in 1826. Book I, “Creation of the World” translated by John Dryden. From http://classics.mit.edu/Ovid/metam.1.first.html.

[8] For Ovid’s narrative of the Flood see Ovid’s Metamorphoses, translated by Anthony S. Kline. 2000. Book I, verses 244-437. (http://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Metamorph.htm#488381093).

[9]Genesis 2:4-3:24. See King James Version at https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Genesis+2%3A4-3%3A24&version=KJV.

[10] Genesis 6:9-9:17. See King James Version at https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Genesis%206:9-9:17.

[11] See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Gilgamesh flood myth’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 13 September 2016, 02:32 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Gilgamesh_flood_myth&oldid=739153725> [accessed 24 September 2016].

[12] For parallels between the Assyrian Tree of Life and the Jewish Kabbalistic Tree of Life, i.e. the Safirotic Tree of Life see THE ASSYRIAN TREE OF LIFE: TRACING THE ORIGINS OF JEWISH MONOTHEISM AND GREEK PHILOSOPHY by Simo Parpola. Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol 52, No. 3 (Jul 1993), pp. 161-208. Published by the University of Chicago Press.

[13] From Helmet of the Urartu king Sarduri II, circa 8th century BCE. Image from Wikimedia commons at Wikipedia contributors, ‘Art of Urartu’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 11 March 2016, 15:11 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Art_of_Urartu&oldid=709543824> [accessed 24 September 2016].

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!