The Enlightenment: The Tree of Knowledge Takes Root

After the fall of the Roman Empire and into the middle and latter part of the Middle Ages in the West, mainly in the period from the 11th century CE until the end of the Renaissance and the advent of the Scientific Revolution, the beginning of which is marked by the work of Copernicus (1473-1543 CE) who upended the basic astronomical assumptions of geocentrism which had been prevalent for the prior three thousand years, the intellectual community and the preservation of the teachings of the Ancient Greek and Latin philosophical texts, philosophy in the broad sense of the word which included astronomy, logics, mathematics, ethics, etc. was primarily centered around Christian monasteries and Churches. The establishment of true institutions of higher learning and educational reform occurred later in the Renaissance, even though the curriculum was still very religious at its core and was propagated and sponsored by Christian Churches and monasteries and otherwise advocated and controlled by the Christian authorities.

During the Middle Ages, translations of the original Greek and Latin texts were not readily available to the public, leading to the propagation of truth by the relatively few and the keepers of knowledge being representatives of various religious authorities rather than stemming from an independent intellectual community. The standard cosmological and astronomical world view at that time was of course geo-centric of course and had its roots again in the works of the Greeks, most notable Aristotle and then Ptolemy from an astronomical perspective, which was then leveraged by Judeo-Christian theology to justify human kind’s special place in the universe as reflected in Genesis, which in turn Mohammad/Islam borrowed and incorporated. Any idea that was put forth that opposed this Judeo-Christian world view where God created mankind in his own image, and where Earth was the center of the Universe, was not received well to say the least and in almost all cases led to excommunication and banishment, which of course makes the work of Copernicus all that more revolutionary given its controversial nature.

Although hard to generalize across all of Western Europe, during the Middle Ages the mode of teaching is most commonly referred to as scholastic, which although was a curriculum that was markedly religious, Judeo-Christian to be more specific, it did included a critical review of the ancient Greek and Roman literature and included core teachings on math, logic, and astronomy among other subjects that today we might see as part of any core curriculum at university. It is from these humble beginnings that a “classical education” was born.

Although the term scholasticism is sometimes associated with a philosophical framework, in this context the term mainly refers to the method of teaching that was employed by academics during the late Middle Ages that involved positing various truths or theorems that were thought to be well established and putting them to rigorous rational test via dialectic means by the students and teachers alike, in some sense harkening back in some respect to the teaching modus operandi of Plato with respect to utilizing the opposing viewpoints on a particular subject to elucidate truth.

Arguably the pinnacle of scholastic thought is in the work by the Italian philosopher and theologian from the 13th century CE Saint Thomas Aquinas. His teachings, which encapsulate in many respects what we consider to be scholasticism today, are captured in his infamous Summa Theologica, a work which although unfinished, was intended to be an instructional and teaching guide for theologians of his day. The work was primarily intended to establish the truth and supremacy of the teachings of the Bible and Christianity, but it did have a philosophical bent however, and it drew on wide variety of philosophical and theological traditions ranging from classical Greek philosophy (Aristotle and Plato), Muslim philosophy (Avicenna and Averroes), the Jewish philosophy of Maimonides, and of course a variety of Christian sources and texts. In the Summa Theologica, a work that is said to have profoundly influenced Dante’s Divine Comedy, Aquinas attempts to establish the unequivocal existence of God as well as establish a moral and ethical foundation within the Christian teachings, as well as the importance of Christ as a messenger of God through which God’s teachings and ultimate salvation can be realized.

Aquinas also wrote several commentaries on Aristotle’s work – On the Soul, Nicomachean Ethics, and Metaphysics – and his metaphysics is markedly Aristotelian despite the theological nature of his work. To Aquinas, as with Aristotle and later Muslim philosophers who interpreted Aristotle’s teachings in a wholly religious context, God is the prime mover and universal first cause from which all motion, all activity emanates and provides the rational basis for the existence of the soul and by extension the justification for a moral and ethical life. Aquinas in no uncertain terms believed and attempted to establish the existence of God and the importance of Christian teachings in general to the salvation of the soul however, but his work is unique in that he draws on many of the different philosophical traditions that came before him and was extremely influential on scholasticism in general which effected the teachings of the Church for the next few hundred years to no small degree.

What is natural cannot be changed while nature remains. But contrary opinions cannot be in the same mind at the same time: therefore no opinion or belief is sent to man from God contrary to natural knowledge. And therefore the Apostle says: The word is near in thy heart and in thy mouth, that is, the word of faith which we preach (Rom. x, 8). But because it surpasses reason it is counted by some as contrary to reason, which cannot be. To the same effect is the authority of Augustine (Gen. ad litt. ii, 18): “What truth reveals can nowise be contrary to the holy books either of the Old or of the New Testament.” Hence the conclusion is evident, that any arguments alleged against the teachings of faith do not proceed logically from first principles of nature, principles of themselves known, and so do not amount to a demonstration; but are either probable reasons or sophistical; hence room is left for refuting them.[1]

The first institutions in the West to be considered Universities in any sort of modern sense of the term were established in Italy, France, Spain and England in the late 11th and the 12th centuries for the study of arts, law, medicine, and of course theology – places of higher learning such as the University of Salerno, the University of Bologna, and the University of Paris. But the pace and acceleration of intellectual thought and teaching really took hold in the West in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries with the more broad availability of texts via the advent of primitive forms of printing alongside the this spread of a pseudo-university system that had been established throughout Europe to teach the intellectual elite. Irrespective of the means by which intellectual thought and scholarship was taught throughout the Middle Ages, a period which extended well into what modern historians call the Age of Enlightenment in the 16th and 17th centuries marked by the spread of universities and advent of printing and greater availability of books to the wider public, despite the markedly Christian theological bias of the curriculum, the Greek and Latin classics remained a core part of the teachings and means of instruction.

Although this culmination of intellectual development is not something that can be pointed to specifically at a place in time per se, it corresponds roughly to what later historians have called the Renaissance, which in turn drove the Scientific Revolution, from which the lives of notable scholars such as Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler and then Newton are products of. The works of these great intellects in turn drove the Scientific Revolution which spearheaded thought and intellectual evolution across a wide range of disciplines in Europe and beyond, disciplines that ranged from the purely philosophical – metaphysics and rational explanation and proof of the existence of God and relevance of Christian Scripture – to the socio-political which attempted to reconcile the role of the state/monarchy and its relationships to its people and subjects as well as the rational justification for morals and ethics, all of which go well beyond what we today call science even though all of these advancements were a product of the Age of Enlightenment in one respect or another.

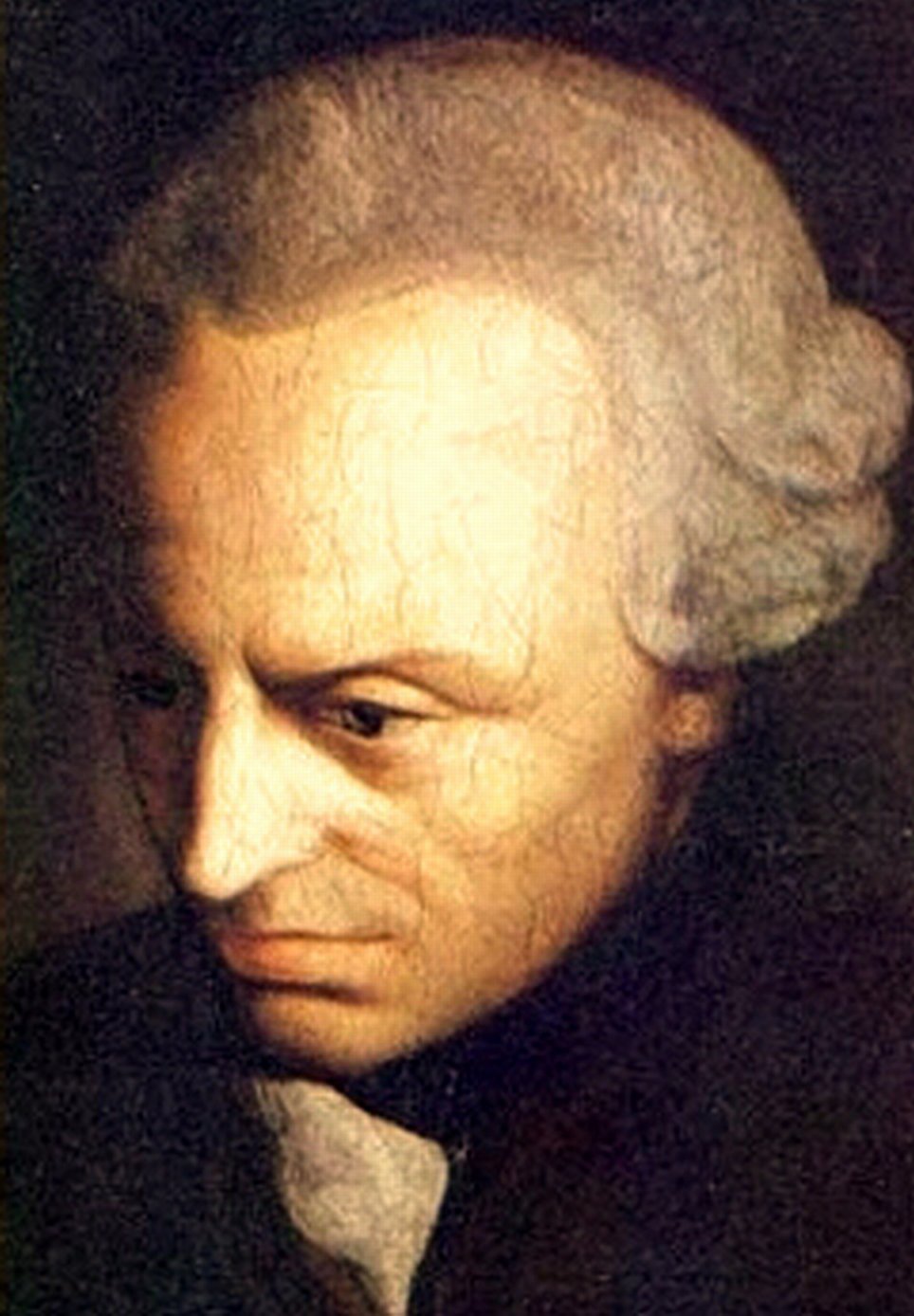

During this time, the core curriculum in these universities if you could call them that was mostly made up of Platonic, Aristotelian, Neo-Platonic, and other Greek and Roman scholarly work in the original Greek and Latin to provide the intellectual framework and semantics within which the world, and in turn God and Christ, should be perceived, an intellectual framework that went well beyond just a blind faith in God and the Bible. But make no mistake about it, these universities and their teachers were very much grounded in Christian faith and belief and the curriculum that was being taught had to align with these beliefs else excommunication and banishment was the norm. This rigid orthodox view of intellectual alignment with the Church lasted right up until what wee refer to as the Age of Enlightenment comes to a close, typically marked by the publishing of the work What is Enlightenment by the eminent German philosopher Immanuel Kant at the end of the 18th century.

So even despite the passage of over a 2000 years after Aristotle and Plato and other Ancient Philosophers that came after them set down their teachings in Ancient Greece and the broader Mediterranean region, a period which was marked by the preeminence of first the Roman, then the Byzantine and Islamic Empires, a good portion of these core ancient Greek and Latin texts and their associated commentaries which provided the metaphysical and theological underpinnings of Abrahamic monotheism, particularly the schools of Aristotle and Plato, still remained a core part of the syllabus and curriculum of the intellectual community.

These works, despite their aged heritage, formed the semantic and metaphysical structure within which intellectual development was pursued up until the Age of Enlightenment where the field of science first emerged as an independent field of study. Even if these ancient works and writings were looked at as in contrast to or in exposition of the current way of thinking or what was to be taught, they still formed the basis of the dialogue and upon which modern interpretations of Scripture were based. Aristotle primarily set the table with respect to logic, metaphysics and the study of natural philosophy, Plato and his subsequent interpreters provided the intellectual connection between Christianity and philosophy and metaphysics in general (Neo-Platonism mostly), and then Ptolemy, Aristotle and Euclid provided the astronomical and mathematical foundations, all the while Plato’s mode of learning, namely dialectic, formed the basis for which learning and education took place, as evidenced by the prevalence of scholasticism in the Middle Ages marked most notably by the writings and subsequent influence of Aquinas.

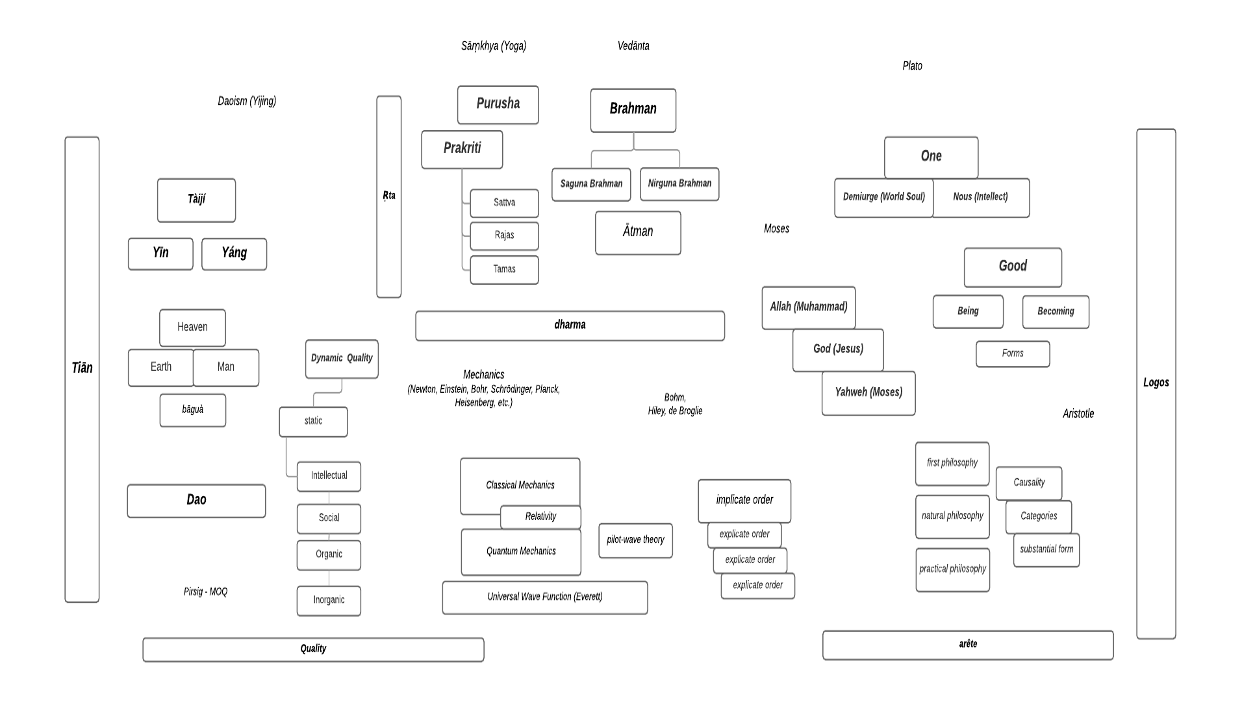

As Charlie began studying the time period and great thinkers from what modern day historians have termed the Age of Reason and the Scientific Revolution in the West, he wasn’t looking for an historical narrative per se but was searching for the roots of this mechanistic and altogether atheistic worldview, the seeds of which he found in the works of the notable philosophers and theologians of this period and yet still struggled to pinpoint its origins, despite the fact that it was very clear that the Ancient Greek and Roman literature provided for the academic foundation of the scholars of this period. After much research, he saw the best way to frame the intellectual developments of this period of tremendous intellectual expansion was via the semantic and logical framework laid out by Aristotle some two thousand years prior, for this was the way the intellectuals of the period approached their studies primarily.

From Charlie’s perspective, the categories of knowledge or intellectual developments of this period were best categorized within the same intellectual context and categorization of knowledge as put forth by Aristotle, or epistêmai in Greek which was the word that Aristotle used. And it was Aristotle’s categorization of the different fields of study, the classification of knowledge itself or what we call today epistemology, which remained the best way to classify the developments of the Age of Enlightenment and the branches of knowledge, of which science was but one, which emerged from this period in our evolutionary history and has carried us through to the 21st century, a century which is marked by deep specialization in all fields, science as well as philosophy and the arts, specialization which was wholly absent from the intellectual pursuits of the 15th, 16th, 17th and 18th centuries in the West.

Although there were a variety of developments in thought and scholarship during the Age of Reason and Scientific Revolution, all of them shattered the very foundations of the belief systems that had been present for the prior two thousand years, namely that the world was created by an anthropomorphic God, that mankind was created in God’s image, that the Bible was to be taken literally with respect to its historical and mythological narrative, and that the Earth was the center of the universe. All of these tenets were at the core of monotheism and the Abrahamic faiths, faiths which provided for the very cultural and socio-political foundations of Western Europe at the time. These intellectual attacks of the Scientific Revolution, if you could call them that, were three pronged from an Aristotelian perspective:

- Theoretical epistêmai / first philosophy: developments in metaphysics or first philosophy in an attempt to establish the existence of the One, or God, via rigorous rational and logical proofs. These developments started mostly with a Neo-platonic and Christian theological bent but later morphed into more sound metaphysical systems which questioned the existence of an anthropomorphic God at all (what could be loosely categorized as the development of deism or naturalism),

- Theoretical epistêmai / natural philosophy: the development and evolution of natural philosophy as a separate branch of intellectual pursuit with the emergence of the foundation of analytical geometry, algebra and calculus alongside developments in astronomy which not only toppled the geocentric conception of the universe but also the notion that mankind held a special place in the universe as was put forth in the Bible,

- Practical epistêmai: developments in socio-political and economic theory that questioned the role of the state and the power of the Church and attempted to establish a science of individual behavior and an optimal form of government, all of which had a profound effect on the evolution and role of government in this period and drove several major revolutions in Western Europe and what was to become known as America.

The scope of intellectual developments during this period were very much aligned with the theo-philosophical developments that were trademarks of Hellenistic philosophical developments except the difference now was that with the proliferation or printing and the acceleration of intellectual exchange, developments along each of these intellectual lines could be done collectively and collaboratively at a much faster pace than could be done in ancient history, certainly not to the extent that peer reviews and collaboration occurs in the modern age with the proliferation of electronic modes of communication but certainly a marked improvement over what had been possible during the Dark/Middle Ages and the centuries that preceded them. The intellectual developments that had marked the prior two thousand years were no longer in the hands of the few, and as the knowledge contained therein spread, its implications were felt more broadly in society.

In many respects, the Age of Enlightenment is best known for its developments in socio-political theory, developments which led directly to the evolution/revolution of the political landscape in Europe and America marked most notably by the English Revolution in 1688, the American Revolution from 1775-1783, and culminating in the French Revolution in 1789-1799 which marks the end of the Age of Enlightenment according to most modern day historians. These socio-political advancements, corresponding roughly to Aristotle’s practical philosophy and following in many respects the tenets set forth in Plato’s Republic, drove not only greater freedom of thought and religious tolerance throughout the West, but also established separation of powers in several key Western governments, the beginning of the principle of separation between Church and State, as well as the establishment of socio-economic optimization and collaboration as the underlying goal of government.

These socio-political developments in practical philosophy that in many respects define the Age of Enlightenment were to name a few:

- The English Thomas Hobbes (1588-1689), who although supported the notion of sovereign authority developed social contract theory in his seminal work Leviathan,

- The empiricist John Locke (1632-1704) whose theories of mind, knowledge, and social contract theory influenced Voltaire, Rousseau and Kant among other Enlightenment thinkers as well as provided for some of the founding principles of the American Revolution,

- The renowned and prolific author Voltaire (1694-1778), who perhaps in many respects best synthesized many if not all of these socio-political developments of this time period in his writings, and

- The Scot Adam Smith (1723-1790), sometimes referred to as the father of modern economics and perhaps best known for his An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations establishing the basis for modern economic theory.

All of these authors and political and social revolutionaries all came from this period of history and did much to establish the foundations of Western government with its separation and balance of powers as well as set the stage for advancements in freedom of thought and exchange that ran parallel with and supported developments along Aristotle’s first and natural philosophical lines, i.e. the advancements of what we today refer to as science which formed the core of the Scientific Revolution which ran parallel to the Age of Enlightenment.

But these authors and their works were concerned about codes of ethics and systems of governance more so than they were concerned with the nature of reality and mankind’s place in it and so in this respect they were of less interest to Charlie other than the fact that without the advancements in these areas, developments in natural philosophy would not have had the opportunity to blossom within social structures that supported freedom of thought as they did. In other words, if the environment for free thinking had not been strongly established in Western Europe during this time period, it would have been next to impossible for the great scientific minds of this time to collaborate and build upon each other’s work to create the breakthroughs in metaphysics and science that emerged as part of what we now call the Scientific Revolution.

But it was developments in first philosophy and natural philosophy that were more interesting to Charlie, for in these areas you saw considerable and rapid developments across a variety of disciplines that fundamentally overturned mankind’s view of the world and his place in it, dovetailing into the mechanistic worldview that Charlie saw as endemic in modern society, the origins of which he was searching for now that his thesis had been established.

Leaving the realm of practical / socio-political philosophy aside then, you had two major themes and areas of advancement of thought that rapidly evolved as civilization in Western Europe began to stabilize at the end of the Middle Ages that established the foundations of modern materialism/mechanism; one along the lines of metaphysics or first philosophy which explored the boundaries of knowledge (epistemology) and its relationship with the divine, the existence of God upon a more rational and reasonable framework and the moral and ethical implications thereof, and another along the lines of science or natural philosophy (astronomy and physics mostly) that radically challenged the conception of the universe and mankind’s place in it that had been prevalent for the prior thousand years or so that directly and forcefully called into question blind faith in Christian Scripture and the Church which had held such a strong chokehold on Western civilization since the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century CE.

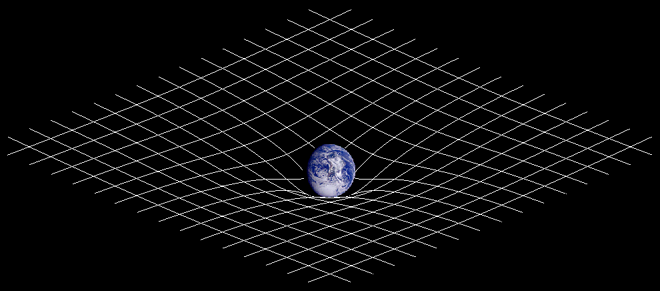

The scientific or natural philosophical developments are typically grouped together in the period known as the Scientific Revolution, a period which begins with Copernicus (1473-1543 CE) in the 16th century and culminates with the work of Isaac Newton (1642-1727 CE) in the 18th century some two centuries later.[2] This period is marked by significant advancements in mathematics, astronomy, biology, medicine and chemistry and did much to transform society’s views on the ability to explain and understand natural phenomenon in general, reinforcing the notion that simple faith in God and the underlying creation ex nihilo was in need of considerable revision and needed to be replaced with a much more complex and rational worldview, one that had its foundations in logic, mathematics, and geometry.

The Scientific Revolution can be viewed through the lens of just a few great thought leaders that made the most lasting contributions to modern science, although it’s important to understand that contributions were made by many others that supported the efforts of these great scholars who will remain obscured by history and the passage of time.

In chronological order you have first and foremost Copernicus (1473-1543 CE) who was the first to formulate a heliocentric model of the universe, followed by Kepler (1571-1630 CE) whose work on the laws of planetary motion provided for some of the foundations of Newton’s laws of gravitation, then Galileo (1564-1642 CE) who made marked improvements on the telescope along with observations which reinforced Copernican’s theories of heliocentrism, then Leibniz (1646-1716 CE), a somewhat more obscure scientist/philosopher who made advancements in calculus, binary number theory and the mechanical calculator, the French philosopher and naturalist Diderot (1713-1784 CE) who was the chief editor of the world’s first Encyclopedia which had profound influence on the dissemination of scientific knowledge throughout Europe, and then of course culminating in the work of Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727 CE) who laid down the foundations for classical mechanics with his laws of motion and theory of universal gravitation.

All of these great thinkers and their associated intellectual advancements came under significant fire during their time from the established authorities which were still very much grounded in Christian fundamentalism, particularly in the early part of the Scientific Revolution which ran up into considerable resistance from the Church establishment which held a strong chokehold on the curriculum of the Universities of the time. Suffice it to say that all of these philosophers, scientists and authors wrote and published at considerable risk of excommunication and banishment, Copernicus and Galileo most notably, speaking to their roles as not only philosophers and scientists, but revolutionaries as well.

These scientific developments were supported with philosophical developments and the advancement of systems of metaphysics during the same period, developments which emphasized the role of scientific method and empiricism, which not only supplanted Aristotle’s theory of knowledge, but also replaced centuries of blind faith and belief in the authority of God and Scripture. As a byproduct of these efforts, which no doubt can be looked at as evolutionary and progressive rather than regressive or stifling in any way, the Aristotelian notion of existence, his being qua being, its relationship to the soul and ethics and politics, along with the context within which the Earth and its most successful species mankind was viewed in the universal world order, was very much turned on its head. All of these developments, revolutionary no doubt (hence the name of the period Scientific Revolution) did not however topple or completely cast aside the notion of existence of God, a fact which was surprising to Charlie as he studied developments during this period, but the connection between natural and political philosophy, physics and metaphysics, and ethics became very much fragmented and in fact forever became separated as independent intellectual pursuits.

[1] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Contra Gentiles. Book I, Chapter 7. From http://www.egs.edu/library/thomas-aquinas/quotes/.

[2] The philosopher and historian Alexandre Koyré coined the term Scientific Revolution in 1939 to describe this period in Western civilization. While the start and end dates of the Scientific Revolution are debated, the publication in 1543 of Nicolaus Copernicus’s De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, “On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres” and Andreas Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica, “On the Fabric of the Human body” are often cited as marking the beginning of this period, sparking follow on developments along many lines in what we today call “science”.

I got this site from my buddy who informed me concerning this web site and at the moment this time I am visiting this site and reading

very informative content at this place.

Good post. I absolutely appreciate this site. Continue the good work!

I’m green too!And to answer your preuiovs inquiry as to whether you have seen my work, I wouldn’t know, as most is seen in small art installations in various galleries etc. However, I did just recently add some still frames of some of my films to my blog. It’s under the title Screeings.Take a look if you like. However, it’s highly unlikely that you’ve seen my work unless you live in my city or even London, which you are in NYC right, so no we’re not in the same city, but I am just west of you; then again you may have been to some conferences about film philosophy and the interactive psychology of the moving image and seen something. I dunno.anyway, I’m green so Yay!have a good weekend.jenji

First off I would like to say wonderful blog!

I had a quick question which I’d like to ask

if you do not mind. I was curious to know how you center yourself and clear your thoughts before writing.

I have had difficulty clearing my thoughts in getting my ideas out.

I do take pleasure in writing but it just seems like the first

10 to 15 minutes are wasted simply just trying to figure out how to begin. Any recommendations or hints?

Thanks!

try meditation. if that doesn’t work try coffee. If that doesn’t work, add more coffee 🙂

sit in contemplation quietly for 15 minutes before writing, meditate if you know how to do that. listen to inspirational music. invoke the Muses.