The Indo-Europeans: The Grandparents of Philosophy

There has been and continues to be much scholarly debate as to what extent the classical Greek philosophical tradition, what we call Hellenic philosophy herein, which classically begins with a study of the so-called “Pre-Socratics”, the bulk of which are Greek in the Hellenic sense of the term (i.e. they spoke and wrote in Greek and lived in a region of Greek influence around the Mediterranean), is of specifically and distinctively Greek origin. We find this debate in antiquity as well, where the two sides can be summed up by Clement of Alexandria the 2nd century Christian theologian and apologist and Diogenes Laertius, the 3rd century CE philosophical historian, respectively.

From Clement of Alexandria (150-215 CE) in his influential apocryphal work The Stromota (or Miscellanies) a reference to the sources and origins of philosophy as a discipline from outside Greece are outlined in some detail, pre-dating Greek philosophical development from which the early Hellenic philosophic schools borrowed or at the very least were influenced by, calling out not only the Chaldeans, Persians (Magi) and Jews, but also the Indian philosophical schools as well (Brahminical tradition as well as Buddha himself).

Zoroaster the Magus, Pythagoras showed to be a Persian. Of the secret books of this man, those who follow the heresy of Prodicus boast to be in possession. Alexander, in his book On the Pythagorean Symbols, relates that Pythagoras was a pupil of Nazaratus the Assyrian a (some think that he is Ezekiel; but he is not, as will afterwards be shown), and will have it that, in addition to these, Pythagoras was a hearer of the Galatae and the Brahmins.

…

Numa the king of the Romans was a Pythagorean, and aided by the precepts of Moses, prohibited from making an image of God in human form, and of the shape of a living creature. Accordingly, during the first hundred and seventy years, though building temples, they made no cast or graven image. For Numa secretly showed them that the Best of Beings could not be apprehended except by the mind alone. Thus philosophy, a thing of the highest utility, flourished in antiquity among the barbarians, shedding its light over the nations. And afterwards it came to Greece.

First in its ranks were the prophets of the Egyptians; and the Chaldeans among the Assyrians; and the Druids among the Gauls; and the Samanaeans among the Bactrians; and the philosophers of the Celts; and the Magi of the Persians, who foretold the Saviour’s birth, and came into the land of Judaea guided by a star. The Indian gymnosophists are also in the number, and the other barbarian philosophers. And of these there are two classes, some of them called Sarmanae, and others Brahmins. And those of the Sarmanae who are called Hylobii neither inhabit cities, nor have roofs over them, but are clothed in the bark of trees, feed on nuts, and drink water in their hands. Like those called Encratites in the present day, they know not marriage nor begetting of children. Some, too, of the Indians obey the precepts of Buddha; whom, on account of his extraordinary sanctity, they have raised to divine honours.[1]

In his prologue to his famed and influential work Lives of Eminent Philosophers Diogenes Laertius denies such assertions, establishing the very foundations of what is sometimes referred to as le miracle grec, or the belief that philosophy as a rational discipline is an altogether uniquely Greek “invention” as it were.

There are some who say that the study of philosophy had its beginning among the barbarians. They urge that the Persians have had their Magi, the Babylonians or Assyrians their Chaldaeans, and the Indians their Gymnosophists; and among the Celts and Gauls there are the people called Druids or Holy Ones, for which they cite as authorities the Magicus of Aristotle and Sotion in the twenty-third book of his Succession of Philosophers. Also they say that Mochus was a Phoenician, Zamolxis a Thracian, and Atlas a Libyan. If we may believe the Egyptians, Hephaestus was the son of the Nile, and with him philosophy began, priests and prophets being its chief exponents. Hephaestus lived 48,863 years before Alexander of Macedon, and in the interval there occurred 373 solar and 832 lunar eclipses. The date of the Magians, beginning with Zoroaster the Persian, was 5000 years before the fall of Troy, as given by Hermodorus the Platonist in his work on mathematics; but Xanthus the Lydian reckons 6000 years from Zoroaster to the expedition of Xerxes, and after that event he places a long line of Magians in succession, bearing the names of Ostanas, Astrampsychos, Gobryas, and Pazatas, down to the conquest of Persia by Alexander. These authors forget that the achievements which they attribute to the barbarians belong to the Greeks, with whom not merely philosophy but the human race itself began.[2]

So while we find Diogenes Laertius pointing to a potentially broad and extensive reach for the potential origins of Hellenic philosophy, and the works of the Pre-Socratics in particular, he himself, no doubt reflecting the traditional beliefs of the Greco-Roman intellectuals of his day, dismisses the theory of the external source of the Hellenic philosophical tradition out of hand despite the acknowledgement given to outside influences by other prominent intellectuals of the time as reflected by Clement of Alexandria’s sentiments quoted above. Hence, we see here illustrated and reflected the long-standing belief that philosophy as a pure intellectual pursuit of wisdom is an altogether “Greek” invention, what Staal refers to as le miracle grec[3]. This question is of course of particular significance to one of the major themes and hypotheses of this work as we try and ascertain as much as is reasonably possible given the scarcity of the textual and archeological evidence from this time period of history to what extent these various theo-philosophical developments throughout the classical period in Eurasian antiquity can be said to be of common origin or common descent.[4]

Perhaps the most well understood and firmly established intellectual theory of cultural diffusion and evolution from this period of antiquity within the geographic region which classical “Hellenic” culture emerged can be found from the academic discipline of linguistics, or the study of (spoken) languages. Almost all modern scholarship surrounding the study of language groups languages into various families, each family being related by a theoretical ancestor which it is believed that all the languages from that family originated from or in some way are closely associated from, making all languages within a given family either sibling languages or cousins so to speak.

One can make a strong case that language and culture, as we understand it and as can be defined as the set of ideas, concepts or principles that connect a given set of people or society from a given region, are in fact synonymous. Or if not synonymous, then very closely related. And it is from the study of ancient (and modern) language families that the close association between the ancient Greeks, the Hellenes, which are attributed with the “discovery” of philosophy, and their neighbors to the East – what much of the academic literature classifies as the “Orient” or “Oriental” but what we prefer to classify as “Eastern” to more closely align the designation with the relative geographical designation – can perhaps best be illustrated.

Pie chart of world languages by percentage of speakers[5]

The two families of interest from this time period of antiquity in the regions we are studying (Eurasia) are Sino-Tibetan, a family of more than 400 languages spoken in East, Southeast and South Asia (of which Chinese is a member), which is second in terms of number of (modern) speakers only to the Indo-European language family which is widely spoken today in almost all of Europe, in Western and Southern Asia (and in turn the Americas) and of which all modern Romance languages, English included, are classified as a member of.[6]

Ancient Greek, the languages spoken in Anatolia (what is now Turkey) as well as ancient Sanskrit and ancient Persian are all in the Indo-European language family and all share not just a similar structure and design but also share many cognates, or word meanings, across a variety of areas that indicate and speak to the similar cultural background of all of these ancient people who (again in theory) all come from a similar background, at least linguistically speaking – in other words who all share a common linguistic, and therefore intellectual, heritage. For again the premise here is that language and ideas, and in turn culture, are all very closely related and affiliated psychological and socio-political phenomena.

Common cognates across these ancient languages are words for kinship (mother, father, sister, brother, etc.), numbers (one, two three, four, ten, one hundred, etc.), animals (cow, horse, sheep, mouse, pig, wolf, etc.), agriculture (grain, field, honey, salt, to plow, to sow, etc.), body parts and processes (eye, ear, tooth, knee, bone, blood, tongue, foot, to breathe, to sweat, to eat, to drink, to live, to die, to know, to find, to see, to think, to say, to ask, etc.), natural features and phenomena (star, sky, fire, wind, snow, light, dark, water, earth, moon, sun, wood, tree, hot, cold, etc.) and a variety of other concepts that can be loosely categorized as “human”. All of these words, ideas and principles reflect symbolically and linguistically, and again socially and culturally, the society and culture within which these languages were spoken and in theory if we believe the linguistic theory itself of language families and evolution, originated in this geographic region – a geographic region which essentially covers (Western) Eurasia in antiquity.[7]

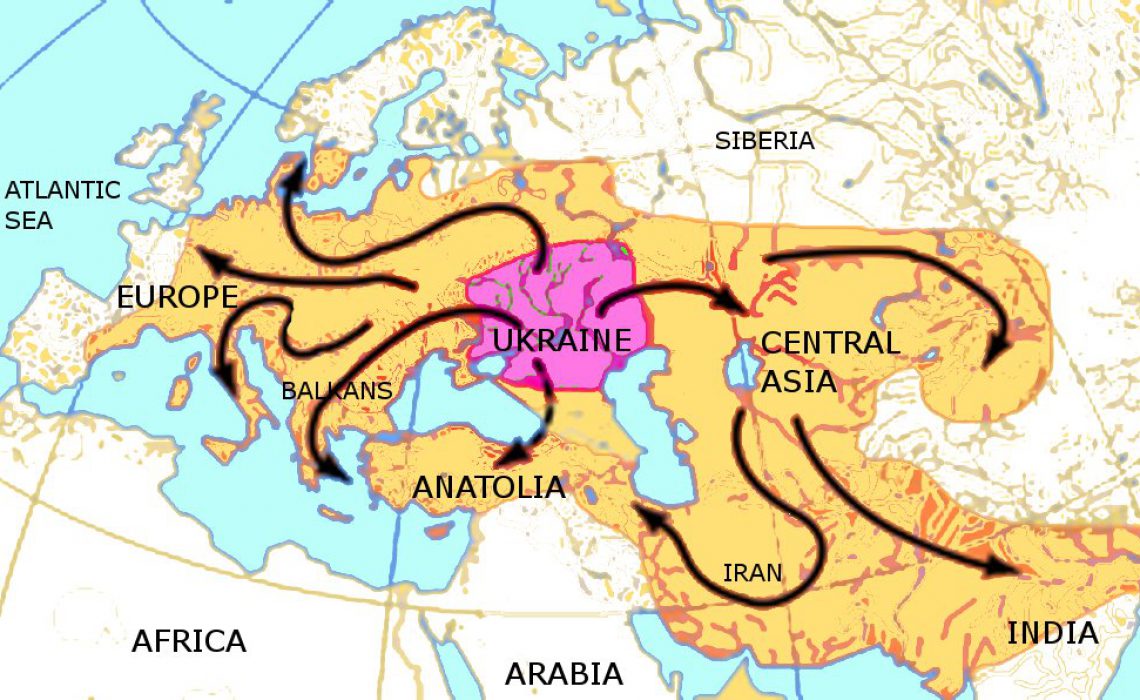

While dating this common ancestral language from which all Indo-European languages are believed to have derived from in some form or another is not an exact science by any means, and it is not even widely held that in fact a common ancestral language (typically referred to as Proto-Indo-European) was ever actually spoken by anyone, based upon the current archeological and linguistic evidence, one can postulate that these word forms and the semantics and syntax of the basic structure of Indo-European languages was developed somewhere in the 4th millennium BCE (give or take a thousand years) and originated and disseminated form a region that is centrally located to where the languages were spoken, i.e. somewhere between the Near East/Asia Minor and the Indian subcontinent from which these Indo-European languages “diffused” or spread, and from which the various dialects or subfamilies of languages within that family developed and evolved.

As an example of how this dating of this Proto-Indo-European language from which the Indo-European languages derived and how they all came to share many of the same words and ideas, one can look at the development of the Romance languages and how they evolved from the Vulgar Latin language which was the lingua franca of the Roman Empire. It took some two thousand years for this early Latin dialect to evolve into the modern languages such as French, Portuguese, Romanian and Italian which all belong to the Italic family of Indo-European languages. If we use this as a benchmark of sorts, using modern languages as an analogy to the Indo-European, one could argue that it took at least two thousand years for the Indo-European languages to develop from whichever language they presumably originated and derived from. In reality though, the rate of progression and evolution of languages from this time period in antiquity was arguably much slower than the last two thousand years (if we presume the rate of evolution runs parallel to the rate of the development and evolution of society and civilization for example) which would tack on an extra thousand years at least just in terms of how long they might have taken to evolve. This in turn would mean that given that Indo-European languages were spoken in the 2nd millennium and early part of the first millennium BCE, if we assume based upon the preceding logic that they took roughly three thousand years to develop, it places this Indo-European parent tongue, again called Proto-Indo-European, in roughly the 5th millennium BCE or so. [8]

Classification of Indo-European languages.[9]

It is from linguistics in fact that the close association between for example Vedic Sanskrit and ancient Persian (Avestan) is found, showing the close relationship between not just these two languages but of course the people that spoke them, people whose theological and religious beliefs are captured in some of the oldest extant literature known to man, i.e. the Persian Avesta and the Indian Vedas, and through which can be ascertained many similar cultural, social and religious beliefs, lending further credence to the linguistic theory itself.

The Indo-Iranian sub branch of Indo-European languages includes the languages of the ancient Persians and Indians, basically the languages spoken by the people and societies that lived in modern Iran and India. This branch includes two sub-branches, Indic (Indo-Aryan) and Iranian. The former classification includes ancient languages such as Vedic Sanskrit (the language of the Rigvéda) and its child language Sanskrit (the language of the later Vedas) as well as modern languages spoken in India such as Hindi, Punjabi, and Bengali. The Iranian sub branch of Indo-Iranian languages include ancient languages such as Old Avestan, sometimes called Gathic Avestan which is the language from the oldest strata of the Avesta, or Gathas, Old Persian which was the primary language spoken in the Achaemenid Empire), Avestan which is the language of the later Avesta Zoroastrian literature, as well as languages from Iranian/Persian later antiquity such as Middle Persian and Parthian, and modern languages such as Farsi (modern Persian), Kurdish and Pashto which are spoken in modern day Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan.

Ancient Greek, part of the Hellenic sub branch of Indo-European languages, was spoken in various dialects throughout the Aegean and Peloponnese peninsula in the latter part of the second millennium BCE and throughout the first millennium BCE. It is perhaps best known in its Athenian dialect form referred to as “Attic”, which is the language of the Homeric epics as well as the language of the early Greek philosophers[10]. Classical Latin, the Latin dialect used by authors such as Ovid, Cicero, Seneca and Marcus Aurelius, and its successor tongues Vulgar and Ecclesiastical Latin which became the predominant languages of the Roman Empire, both also belong to the Indo-European language family, under Italic branch of Indo-European languages, sister and cousin languages to the Hellenic tongues. Again, all modern Romance languages such as Romanian, Italian, French, Spanish, Danish, German, etc. all originate from Vulgar Latin language, the lingua franca of the Roman Empire.[11]

This development of philosophy itself runs parallel not coincidentally to the development and proliferation of writing throughout the region of Hellenic influence. For the development and exploration of ideas and concepts which came to be grouped together under the heading of philosophy, as distinguished from the mythological tradition which preceded it (again as reflected by the writings attributed to Homer and Hesiod), arguably required an advanced system of writing within which these complex sets of ideas and their interrelationships could be explored. In other words, in order for the oral tradition which was characterized by myth and parable and compressed verse based language which facilitated the faithful transmission of theo-philosophical ideas from generation to generation to evolve into a more complex and fuller system of philosophy, a written language and an intellectual tradition surrounding the writings of various thinkers is absolutely necessary. In fact, one could argue that Platonic philosophy itself, as it survives down to us in its classic dialogue form, illustrates this very fact – i.e. oral transmission of ideas explored through what has come to be called dialectic by Aristotle and what is referred to typically as Socratic method in Plato’s works in and of itself shows how a complex system of philosophy can be constructed from the exploration, and documentation, of ideas in written form.

It is no accident that as the Greek alphabet system, from which the Roman alphabet originated from, which was “invented” in the 8th and 7th centuries, a system borrowed from the Phoenicians (i.e. the Phoenician alphabet from which the Greek alphabet evolved from), becomes prevalent at the same time that the Homeric epics are written down, and in turn marks the beginning of the Hellenic philosophical tradition. For again writing itself is a necessary condition (not necessary and sufficient) for the development of philosophy.

To summarize then, as we look at the attempt at the very beginnings of philosophical inquiry, of rational thought really, in the second half of the first millennium BCE more or less, we find similar developments – both culturally and technologically – that support this advancement, this intellectual revolution if we may call it that, across virtually all of Eurasia. In each of these respective geographic and socio-political centers within which civilization emerges, we see an attempt by each of these peoples, the first philosophers, to attempt to answer various questions about the nature of reality and the “universe”, its component parts and pieces, as well as how best the individual, as well as the society and people at large, are to live within this (fundamentally theological, i.e. “divine”) world. This enquiry happens almost simultaneously from amongst the various social, political, linguistic and of course “intellectual” traditions which emerge at this very unique time in our history – what some call the Axial Age given that in a very real sense it represents the time period which many of the foundational aspects of civilized society emerged.

We find these similar lines of enquiry, the manifestation of the same intellectual journey to a large extent, in the Hellenic theo-philosophical tradition to the West, in the Upanishadic and early Indian philosophical tradition on the Indian subcontinent to the East and even to the Far East in ancient China in the Far East, each of which started to formulate, in writing, their own conception of reality, what today in philosophical circles we would refer to as an ontology, as well as the boundaries of what can be said to be real or true, what is referred to as epistemology in modern philosophical circles.

In its initial formulation, at least with respect to lasting influence and persistence of teachings, in the West, in the Hellenic theo-philosophical tradition, this intellectual endeavor takes shape in the works of Plato as his theory of forms[12], which ultimately leads to his notion of the Good , establishing the intellectual, and metaphysical, foundations of Christianity and monotheism.

To the East on the Indian subcontinent, similar intellectual efforts were underway, and in what has come to be known as the Indian theo-philosophical tradition, and in the Upanishads in particular, the core metaphysical (and theological) constructs of Ātman and Brahman were established, each of which is akin to and mapped directly with the notion of what we in the West have come to refer to as “Soul”, one at the individual level and another at the cosmic level. In the Far East, an alternative metaphysical and ontological picture emerges, where emphasis is on the notion of change, cycle, and process – what comes to be known as the Dao, or simply the “Way” – rather than on any one substance, principle, form or idea.

In each of these traditions however, the notion of the emergence of the physical universe, along with mankind itself, out of some kind of divine, cosmic, creative event, which in turn is presided over by some type of divine, immortal being (i.e. a god or gods) is an integral part of the respective belief system, even if it is not explicitly called out or emphasized as such. Furthermore, in each of these traditions, the idea of some immortal or persistent entity that is tied or affiliated to an individual person that persists beyond death is also presumed and fully integrated into the respective belief system, even if it again is manifest, referred to or called, something different and/or it is given a different emphasis, in each of the theo-philosophical systems from antiquity across Eurasia.

The primary distinction however between what we shall refer to as Indo-European philosophy[13] and effectively the theo-philosophical systems of the Far East, is the emphasis on the notion of the Soul not just as an ontological predicate upon which reality is perceived, but also as a cornerstone metaphysical and intellectual construct from which reality is effectively defined.

This idea of the Soul, and its preeminent place within the ontology of the theo-philosophical systems in question, one of the unique elements of what we are calling Indo-European theo-philosophy, can be found for example in both the Hellenic theo-philosophical system, in all its variants in fact, as well as the Indian, or Upanishadic, theo-philosophical traditions. The reality, and immortality, of the Soul plays a significant role in the overall theo-philosophical system articulated by Plato, as a metaphysical entity that exists as the form, or underlying idea, of a person or human being, and also as the underlying metaphysical principle upon which Plato’s notion of virtue, or excellence (arête) is based, upon which both his ethical as well as political philosophy rests in fact. The notion of Ātman, the Indian theo-philosophical corollary to the Hellenic Soul, plays a very similar role theo-philosophically in fact, being perceived as an immortal construct which underpins not just the individual person or psyche (jiva), but also represents the cornerstone principle or idea, metaphysical construct, upon which its system of ethics is based.

In contrast, in the Chinese theo-philosophical tradition, which is not of Indo-European heritage or descent, while a notion of ancestral spirit is no doubt present[14], it does not carry the same ontological or metaphysical significance as it does in the theo-philosophical systems we are categorizing, again along linguistic (and in turn intellectual and ultimately theological) lines, as “Indo-European” . We do not find in the Chinese theo-philosophical tradition for example, the same ontological emphasis on this construct of the Soul, that element or component of the person or human being which persists beyond death, that we find in its Western theo-philosophical counterparts, even if it can be argued that the role of the realm of spirit and the existence of some form of life associated with individual existence does in fact persist beyond death[15].

The Indo-European theo-philosophical tradition also subsumes this idea of the anthropomorphic creator, even as it evolves in later renditions to more of an abstract concept rather than an anthropomorphic deity per se. As we find in the Hellenic theo-philosophical tradition as the penultimate god in the pantheon, i.e. Zeus, which morphs into the more abstract metaphysical notion of the Good, or the Cosmic Soul of Plato. We also find similarly in the Indian theo-philosophical tradition, the Vedic, anthropomorphic deity Puruṣa or Brahmā, which morphs into the more abstract concept of Brahman in the Upanishads.

This notion of universal creation by some anthropomorphic being, or god, also persists into the Abrahamic monotheistic traditions as well, the notion of a single anthropomorphic deity resting of course at the very heart of the Judeo-Christian theological tradition as Yahweh in the Old Testament or simply God in the New Testament, and also manifesting in the Islamic theo-philosophical tradition as Allāh, the primordial one true God of the Qurʾān.

The strength and persistence of the Abrahamic religions which are a hallmark of the theological developments in the West in the first millennium CE in fact arguably stems not from their unique characteristics necessarily, their relative truth as you might say, but due to the continuity and proliferation of these characteristically Indo-European theo-philosophical belief systems that had already been present throughout the geographic and cultural landscape within which these monotheistic belief systems took root – the seeds had been sown to a large degree, prior to the inception and spread of monotheism throughout the Mediterranean initially and then through and throughout the Roman Empire eventually.

In other words, a case can be made that as (Abrahamic) monotheism evolved and spread, it found that the people and societies were already conceptually, and to a large extent theologically, prepared for the next step in religious evolution as it were – the jump from a pre-historic, myth based narrative with many gods and deities representing many different forms or aspects of nature, to a more idealistic and abstract metaphysical system where the universe in all its forms was thought to have emanated, or originated, from a single divine anthropomorphic figure that ultimately held dominion over the entire world order. In this broader intellectual context, Plato’s concept of universal creation, emanation really, that we find in the Timaeus for example, can be seen as a more allegorical interpretation, a close relative as it were, to the of the universal creation story that we find in Genesis, as opposed to a wholly distinctive take on universal creation.

[1] Clement of Alexandria, The Stromota, Chapter XV, “The Greek Philosophy in Great Part Derived from the Barbarians.”. Kirby, Peter. “Historical Jesus Theories.”Early Christian Writings. 2014. 1 Oct. 2014 . <http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/clement-stromata-book1.html>.

[2] Lives of Eminent Philosophers. Diogenes Laertius. R.D. Hicks. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1972 (First published 1925). Prologue. Verses 1-3. From http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0258%3Abook%3D1%3Achapter%3Dprologue.

[3] “Greek and Vedic Geometry” by Frits Staal. Published in the Journal of Indian Philosophy in 1999 by Kluwer Academic Publishers. Vol. 27, No. 1/2, pg. 105.

[4] In particular, significant work has been done to establish the connection and similarities between the theo-philosophical systems of the Indo-Aryans, i.e. ancient Hindu and Vedic, and the Greeks, in particular the Pre-Socratics and Plato. As specific examples one can refer to a) Early Greek Philosophy and the Orient by Martin Litchfield West, published by Oxford: Clarendon Press in 1971, b) an article on the similarities and potential connection (borrowing) of mathematical developments in Classical Greece from ancient Vedic texts – specifically the contents of the Śulbasūtras which contains information surrounding fire altar construction – by Frits Staal, department founder and Emeritus Professor of Philosophy and South/Southeast Asian Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, entitled “Greek and Vedic Geometry” published in the Journal of Indian Philosophy in 1999 by Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Vol. 27, No. 1/2, pp. 105-127], c) the chapter entitled “Prehistory of Presocratic Philosophy in an Orientalizing Context” authored by Walter Burkert, a former German professor of classics at the University of Zurich, Switzerland who was a renowned scholar of Greek mythology mystery cults from the Oxford Handbook of Presocratic Philosophy, edited by Patricia Curd and Daniel W. Graham. Oxford University Press, 2008. [Chapter 2, pages 55-85], d) the book The Shape of Ancient Thought by Thomas McEvilley, a renowned art critic and expert on ancient Greek and Indian culture and language from Rice University and the School of Visual Arts in New York City published in 2002 by Allworth Press in New York that maps out the extensive similarities and cultural borrowing between the ancient Sumer-Babylonians, Assyrians, Persians, Greeks and Indo-Aryans in the 2nd and first millennium BCE, and e) The “Roots of Platonism and Vedānta: Comments on Thomas McEvilley” by John Bussanich, professor of Philosophy at the University of New Mexico published in the International Journal of Hindu Studies, Jan 2005 [Vol. 9, No. 1/3, pp 1-20] which analyzes and criticized the views and positions put forward by McEvilley in his work.

[5]From Wikipedia contributors, ‘List of language families’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 5 October 2016, 05:33 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=List_of_language_families&oldid=742688812> [accessed 5 October 2016].

[6] This theory of language origination and dissemination in philology is similar to the approach of modern biology in its classification of various animals and plants into various species, genus and family designation, a designation that is hierarchical in nature and also maps back to the formulation or origination of species and life on earth, aligning with Darwin’s theory of natural selection.

[7] See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Indo-European vocabulary’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 28 September 2016, 12:57 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Indo-European_vocabulary&oldid=741589022> [accessed 28 September 2016].

[8] “It is highly probable that the earliest speakers of this language originally lived around Ukraine and neighboring regions in the Caucasus and Southern Russia, then spread to most of the rest of Europe and later down into India. The earliest possible end of Proto-Indo-European linguistic unity is believed to be around 3400 BCE.” From 1. Cristian Violatti, “Indo-European Languages,” Ancient History Encyclopedia, last modified May 05, 2014, http://www.ancient.eu /Indo-European_Languages/. Note our estimates based upon the heuristic model above place the language some two millennia earlier in antiquity. It’s also worth noting that at least two of the three primary languages believed to have been spoken throughout the Assyrian Empire, Akkadian and Aramaic, are from the Afro-Asiatic family of languages rather than Indo-European so while this Empire clearly held sway over the area in question in the Near East and Mediterranean in the 2nd millennium BCE or so, the wave of cultural diffusion represented by Proto-Indo-European must have pre-dated the influence of this civilization, consistent with the premise of a date of the 5th or 4th millennium BCE.

[9] Red: Extinct languages. White: categories or unattested proto-languages. Left half: centum languages; right half: satem languages. From Wikimedia Commons; from Wikipedia contributors, ‘Indo-European languages’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 21 October 2016, 19:39 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Indo-European_languages&oldid=745547078> [accessed 21 October 2016].

[10] Some of the earliest known forms of the ancient Greek language were spoken by the Mycenaeans, a culture which flourished in the Mediterranean region. what later came to be known as the area of Hellenic influence, in the middle and latter part of the 2nd millennium BCE.

[11] All modern Romance languages in fact, such as Romanian, Italian, French, Spanish, Danish, German, etc. all originate from Vulgar Latin in fact under the Italic branch of Indo-European languages. Again see 1. Cristian Violatti, “Indo-European Languages,” Ancient History Encyclopedia, last modified May 05, 2014, http://www.ancient.eu /Indo-European_Languages/.

[12] In the Greek εἶδος, or eidôs meaning “form”, “essence”, “type”, or “species” along with the complementary notion of ἰδέα, or idea, meaning “form” or “pattern”. Both Greek words incidentally come from the Indo-European root “to see”. See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Theory of forms’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 25 October 2017, 16:23 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Theory_of_forms&oldid=807055180> [accessed 30 October 2017].

[13] Following the linguistic theory from philology, the study of languages, which holds that there was a foundational people and language from which all Indo-European languages originally were derived from, or at the very least were heavily influence by that originated somewhere in the Near East and which ended up spreading across most of the Mediterranean and into the Indian subcontinent and parts of Asia. For a more detailed look at the theory, as well as some of its variants, see http://www.humanjourney.us/indoEurope.html.)

[14] In Chinese philosophy, and in particular in the theo-philosophy attributed to the Confucian school, veneration and consideration, akin to worship in a sense, of ancestral spirits or forefathers, shén (神) does in fact play a significant role, but much more in terms of ritual and ethical or moral precepts – the core characteristics of Confucian philosophical thought in fact – rather than as again an ontological or metaphysical, or even theological, principle or concept.. While shén roughly translates into English as “spirit” or “god”, the word can take on a much broader and diverse set of meanings depending upon context. See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Shen (Chinese religion)’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 2 August 2017, 21:26 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Shen_(Chinese_religion)&oldid=793612697> [accessed 30 October 2017].

[15] As we find for example in the ancestral worship practices that persist even in modern China, practices that represent a key element of Confucian theo-philosophy.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!