Aristotle’s Metaphysics and Theology: On Being, the First Mover and Love (Eros)

One of the most preeminent philosophical principles that underpins Western thought, one of the foundational presumptions of modern Science in fact, is the notion of causality, or what we refer to more specifically within the context of 20th century Science as causal determinism. This doctrine, the belief that our knowledge of reality, is effectively determined by causation, and that every action or state of being has come to be as such due to the compilation of, or the direct result of, a series of causal based actions or events, is directly attributed to Aristotle’s theory of causality.[1]

In order to fully appreciate and understand Aristotle’s philosophy, one must understand his theory of causality which underpins his epistemological framework as well as his metaphysics to a large degree. It is Aristotle’s theory of causality which comes to underpin and ultimately define his notion of being qua being upon which Aristotle ultimately comes to defines existence itself, and it is his causal framework, described below, that he uses as the intellectual foundation for his metaphysics. In other words, the existence of a thing, its substance or essence, is understood and defined by the things which bring said substance or thing into existence, i.e. its causes.

Aristotle’s theory of causality, sometimes referred to as the four causes, or four-causal theory, rests on the assumption that knowledge of a thing, or being itself really, is fundamentally predicated upon a complete understanding of how, and why, such a being has come into existence. That is to say, to understand the nature of any being, anything that can be said to exist, one must come to a full and complete understanding as to all of the underlying causes that have brought said being into existence. From Physics, for example, we find:

This is most obvious in the case of animals other than man: they make things using neither craft nor on the basis of inquiry nor by deliberation. This is in fact a source of puzzlement for those who wonder whether it is by reason or by some other faculty that these creatures work—spiders, ants and the like. Advancing bit by bit in this same direction it becomes apparent that even in plants features conducive to an end occur—leaves, for example, grow in order to provide shade for the fruit. If then it is both by nature and for an end that the swallow makes its nest and the spider its web, and plants grow leaves for the sake of the fruit and send their roots down rather than up for the sake of nourishment, it is plain that this kind of cause is operative in things which come to be and are by nature. And since nature is twofold, as matter and as form, the form is the end, and since all other things are for sake of the end, the form must be the cause in the sense of that for the sake of which. (Phys. 199a20–32)[2]

Here we find a very apt description of another one of Aristotle’s metaphysical cornerstones, i.e. the notion of hylomorphism. In Aristotle’s philosophy, the known universe consists again not of things necessarily but of beings, entities that are primarily defined by the notion of substantial form, a so-called “hylomorphic” construct where being, or substance (ousia) is a compound of matter as well as its underlying form. In contrast, to Plato the underlying form, or idea, of thing not only “informed” its existence, the thing itself actually depends upon its underlying form in order to exist at all.[3]

To take this argument one step further, and a precursor to an understanding of Aristotle’s theology, to Aristotle, existence itself is to a large extent is defined by its underlying purpose or meaning. That is to say, using Aristotle’s terminology, for everything that can be said to “exist”, there must be an underlying purpose that brings said being into existence, this is what Aristotle refers to as the final cause. This idea of existence being ultimately dependent upon some underlying purpose then, or meaning, in turn from a theological and cosmological standpoint yields the necessary existence of some penultimate, or first cause, which later Islamic philosophers interpreted as equivalent to God, or Allāh, effectively placing the complete Islamic theological framework, their theology, directly on the back of Aristotle’s rational metaphysical model of the universe and epistemological framework.

In Physics, we find a detailed explanation of his theory of causality, a description of the four causes, as:

One way in which cause is spoken of is that out of which a thing comes to be and which persists, e.g. the bronze of the statue, the silver of the bowl, and the genera of which the bronze and the silver are species. In another way cause is spoken of as the form or the pattern, i.e. what is mentioned in the account (logos) belonging to the essence and its genera, e.g. the cause of an octave is a ratio of 2:1, or number more generally, as well as the parts mentioned in the account (logos). Further, the primary source of the change and rest is spoken of as a cause, e.g. the man who deliberated is a cause, the father is the cause of the child, and generally the maker is the cause of what is made and what brings about change is a cause of what is changed. Further, the end (telos) is spoken of as a cause. This is that for the sake of which (hou heneka) a thing is done, e.g. health is the cause of walking about. ‘Why is he walking about?’ We say: ‘To be healthy’— and, having said that, we think we have indicated the cause.[4]

From this we can gather that Aristotle’s intellectual framework for determining the full scope of knowledge of a thing, the core of his epistemological framework, which consists of four distinct but related causes, the second of which corresponds loosely to Plato’s theory of forms.

- the material cause of a thing or that from which a thing is made,

- the formal cause of a thing or the structure to which something is created (loosely corresponding to Plato’s idea of Forms or Ideas),

- the efficient cause of a thing which is the agent responsible for bringing something into being, and

- the final cause of a thing (telos[5]) which represents the purpose by which a thing has come into existence.

The first two causes, the material and the formal, are born out of the importance that Aristotle places on the notion that being, which is the term he (and Plato in fact) uses to define reality, or existence – i.e. “things” – requires both form as well as substance, in order for it to be brought into existence as it were. These two basic elements of Aristotle’s epistemological and ontological system are typically described using the term “hylomorphic” denoting the complex and interdependent relationship they have as they come together to establish Aristotle’s substantial form, arguably the basic building block in Aristotle’s ontology.

The third of the four causes, the efficient cause, represents that which brings something into being, incorporating to a large degree his physics into the system, and the final cause (no pun intended) is Aristotle’s final cause, which integrates the notion of purpose, or meaning (from the Greek telos meaning “end”, “purpose” or “goal”) directly into Aristotle’s epistemological framework, one of its distinguishing features in fact.

Aristotle’s doctrine of substantial form to a large degree can be seen as, and perhaps best understood as, an enhancement to Plato’s notion of forms, the fundamental building block in Plato’s epistemology, but Aristotle grounds the forms, ties them as it were, directly into the material world with ousia, the Greek word for substance but is perhaps better translated as essence. The epistemological system as a whole not only rests on the hylomorphic construct of substantial form, but also quite elegantly integrates the notion of change as well with the notion of the efficient cause which represents that which brings something into existence – a feature that is arguably lacking in Plato’s metaphysics. Form in Aristotelian philosophy, is that which gives shape to matter, and is the source from which potentiality yields actuality, informing as it were, and providing the intellectual guiding principle, to things that can be said to exist.

Although it is open to debate whether or not Aristotle presupposes that all four causes must be present in order for a thing to exist (in fact in some cases he cites examples of which all four causes are not present but yet existence of said thing is still adequately explained[6]), this idea of a required efficient cause is unique to Aristotle relative to the philosophers that came before him and forms the basis upon which much of his theory of natural philosophy rests. This efficient cause of Aristotle can also be seen as representing the connecting principle of Plato’s concept of forms to Plato’s illusory realm of the senses, representing again an expansion of Plato’s metaphysics as reflected in the theory of forms rather than a complete abandonment of it.[7]

Perhaps the best way to understand Aristotle’s theology – outside of his theory of causality which speaks to the question as to the existence of some underlying final cause, purpose as it were, for the entirety of existence – is to contrast his theological system as we understand it with that of Plato’s, specifically as represented in the Timaeus along with his theory of forms as outlined in The Republic.

Aristotle does not necessarily directly attack Plato’s belief in the existence of a divine creator per se, Plato’s Demiurge, but he did argue, as we have seen, that Plato’s idealism lacked the rational foundations to truly explain the totality of existence, what has come to be understood as being qua being. That is to say, Plato’s theory of forms, despite being a powerful metaphor to describe the what Plato at least considered to be the underlying illusory nature of reality, did not truly and completely describe how a form or idea transformed or constituted being in its myriad of representations or manifestations.

Aristotle however, takes pains to articulate these concepts in detail, how form underpins existence as a component of substantial form, i.e. Aristotle’s hylomorphic conception of existence, but nonetheless does not carry the same ontological significance as substance, i.e. ousia. Through the notion of substantial form then, Aristotle provides not only the rational underpinnings of his ontology, his description of reality or the totality of being as it were, but also the rational foundations of his conception of the Soul, and as such his philosophy of ethics.

In Metaphysics Book XII, we perhaps find the most intriguing and forthright evidence of how Aristotle conceives of what we call in the West God, but to Aristotle represents a primordial ontological entity that sits behind the natural world and all of its phenomena.

There is something which is eternally moved with an unceasing motion, and that circular motion. This is evident not merely in theory, but in fact. Therefore the “ultimate heaven” must be eternal. Then there is also something which moves it. And since that which is moved while it moves is intermediate, there is something which moves without being moved; something eternal which is both substance and actuality. [8]

Here we find Aristotle’s unmoved mover, that which sets the entire universal order, the heavens in motion. His rational deduction which leads to its existence, is based upon his principles of change, or motion, from which deduces that there must exist something eternal and unchanging behind it. Furthermore, this primordial entity, is both substance and actuality, which in Aristotle’s metaphysical and epistemological framework puts it in the category of things that have a material existence. The unmoved mover is not an idea or a concept – something that has potentiality but is not yet actualized – it’s an “eternally” existent entity, a being, which sits behind the motion of the heavens.

Now that the rational necessity of the unmoved mover has been established, according to principles of Aristotle’s Physics primarily, Aristotle goes on to apply his causal theory to it, specifically the final cause, outlining its application to immovable objects in general, and – somewhat surprisingly – ascribes the source of the motion of said objects to love, blessed Eros.

That the final cause may apply to immovable things is shown by the distinction of its meanings. For the final cause is not only “the good for something,” but also “the good which is the end of some action.” In the latter sense it applies to immovable things, although in the former it does not; and it causes motion as being an object of love, whereas all other things cause motion because they are themselves in motion. Now if a thing is moved, it can be otherwise than it is. Therefore if the actuality of “the heaven” is primary locomotion, then in so far as “the heaven” is moved, in this respect at least it is possible for it to be otherwise; i.e. in respect of place, even if not of substantiality. But since there is something—X—which moves while being itself unmoved, existing actually, X cannot be otherwise in any respect. For the primary kind of change is locomotion, and of locomotion circular locomotion; and this is the motion which X induces. Thus X is necessarily existent; and qua necessary it is good, and is in this sense a first principle. For the necessary has all these meanings: that which is by constraint because it is contrary to impulse; and that without which excellence is impossible; and that which cannot be otherwise, but is absolutely necessary. [9]

In applying his causal theory, along with rational deduction, he ascribes to this primordial ontological principle – again the unmoved mover – not just as a requisite entity in and of itself, but also as representative of benevolence in some way, ascribing “good” behavior to it within the context of his ethical philosophy. The introduction of Eros into the rational framework is interesting, betraying Aristotle’s uniquely Hellenic, and Platonic heritage, where Eros of course plays such a prominent role in the Theogony of Hesiod. And Hesiod’s Eros, is no stranger to Plato’s Good, the form of forms who provides order – logos – to the world in the Timaeus.

Aristotle goes on describe this entity, this being, referring to it more specifically now as it relates to the notion of God, or theos, the ancient anthropomorphized figure that holds dominion over the natural world.

Such, then, is the first principle upon which depend the sensible universe and the world of nature. And its life is like the best which we temporarily enjoy. It must be in that state always (which for us is impossible), since its actuality is also pleasure. (And for this reason waking, sensation and thinking are most pleasant, and hopes and memories are pleasant because of them.) Now thinking in itself is concerned with that which is in itself best, and thinking in the highest sense with that which is in the highest sense best. And thought thinks itself through participation in the object of thought; for it becomes an object of thought by the act of apprehension and thinking, so that thought and the object of thought are the same, because that which is receptive of the object of thought, i.e. essence, is thought. And it actually functions when it possesses this object. Hence it is actuality rather than potentiality that is held to be the divine possession of rational thought, and its active contemplation is that which is most pleasant and best. If, then, the happiness which God always enjoys is as great as that which we enjoy sometimes, it is marvellous; and if it is greater, this is still more marvellous. Nevertheless it is so. Moreover, life belongs to God. For the actuality of thought is life, and God is that actuality; and the essential actuality of God is life most good and eternal. We hold, then, that God is a living being, eternal, most good; and therefore life and a continuous eternal existence belong to God; for that is what God is.[10]

In this passage, arguably representing the very summit of Aristotle’s theology, he bridges the gap between the first mover, the Good (in the Platonic sense), and the existence of God as benevolent, fully actualized being that is “eternal” and the “most good”. Interestingly, this deduction is made by applying some of Aristotle’s psychological theories, his theories surrounding the Soul and its sensory apparatus and the relationship of thought and “participation in the object of thought” – once again using his notion of actuality (versus potentiality). He completes the passage with the conclusion that best life, the “most good”, Is one that is lived in the likeness of God, i.e. the contemplative life.

And in the last line, we can find the seeds of the Stoic notion of corporealism as well as, perhaps somewhat less directly, the Neo-Platonic notion of emanation, where God is held to be not just a primordial entity that sets the heavens in motion, or some idealistic conception of the most Good, but is equated in the broadest metaphysical sense with all of existence as a “living being, eternal, most good”, and equated with “life and continuous eternal existence” which “belong to God, for that is what God is.”

While a bit of a circuitous journey no doubt, we see here in Aristotle’s argument the application of many of his philosophical doctrines and tenets, from his theoretical framework of motion and change which underpins his Physics, to his theory of causality combined from a teleological perspective (final cause), using logic to argue for the existence of God as actualized substance, and finally the combination of some of his psychological theories around perception and apprehension along with his physical theories on actualization and potentiality that are used to not only argue for God’s existence as a contemplative being, but one that actually exists, is eternal and Good, and ultimately is equated with the entirety of existence – existence itself really.

While Aristotle’s theological beliefs are certainly open to debate, it is nonetheless safe to say that his theology differed from that of his teacher and predecessor Plato, on both physical and epistemological grounds – physical in the sense that his notions of substantial form, actuality and potentiality all represent the basic building blocks of not only his notion of Physics, but his theological framework as well, and epistemological in the sense that his understanding of God rests squarely within his overall theory of knowledge, and more specifically his theory of causality as the final cause of the universe as it were.

But despite these differences, there are some very basic and fundamental – and oft overlooked – similarities between Aristotle and Plato’s theology. While within the context of Plato’s idealistic theology we find an ontology that is fundamentally predicated on ideas, or forms rather than on any material substance (in contrast to Aristotle), God is nonetheless represented in both philosophical systems as the ultimate creator – Aristotle’s prime mover and Plato’s Demiurge – of a fundamentally rational and ordered universe. It is the core belief in the creation of an ordered, rational universe by a divine, primordial being in fact, that is not only central to the theologies of Plato and Aristotle, but also represents the fundamental theological, and cosmological, ordering force of all of creation itself, all of existence, all throughout Eurasia in antiquity in fact.

In particular in the Hellenic philosophical tradition however, and again both Plato and Aristotle are no exceptions here, this abstract concept of reason itself as it were – what came to be understood as Logos which played such a prominent role in the Stoic philosophical tradition as well as early Christianity in particular – comes to play a fundamental role not only in theology and cosmology, but in a broader sense in the Hellenic philosophical tradition as a whole. We can see this principle of reason or order at the very root of the Hellenic cosmological tradition in fact, with the very word for cosmos, the Greek kosmos, meaning literally “ordered” or “harmoniously arranged”.

And then of course we find this notion of order, or reason, as a fundamental ontological principle not only in Aristotle’s Metaphysics, but also in Plato’s Timaeus and also in Pythagorean philosophy. The Hellenic philosophical tradition as a whole in fact, to a large degree has become known for, is fundamentally characterized by, its fundamentally rational basis – the first theo-philosophical tradition in antiquity, at least in the Western world, to establish a fully rational framework for reality. For in the Hellenic philosophical tradition, the epistemological, metaphysical and ontological positions are effectively established by, are rooted in, reason itself as it is understood through the system of logic that is also (for the most part) a fundamentally Hellenic discipline that is tied to the very heart of the philosophical tradition itself. It is reason itself, as an ontological precept that again comes to be known as Logos, from which all knowledge, all existence, is born. This is one of the hallmarks of Hellenic philosophy in fact, and certainly the philosophical traditions of Plato and Aristotle represent this just as much as, if not more so, than any other philosophical tradition in the Hellenic world.

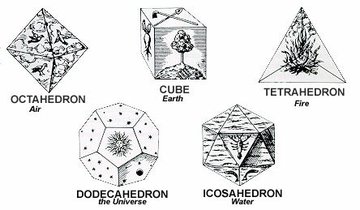

It is this concept of the abstract principle of reason in fact, as a further abstraction to the discipline of logic, a discipline which plays an integral role in virtually all of the schools of classical Hellenic philosophy, which forms the basis of not just geometry, but of mathematics as a whole as well. And it is these two disciplines in fact – geometry and mathematics – that, outside of the discipline of philosophy as a whole, represent perhaps the defining contributions of the ancient Greeks, the Hellenes, to Western thought. And it is these two disciplines as it turns out, which are also integrally linked to cosmology and theology throughout almost the entire Hellenic philosophical tradition, with again Plato and Aristotle being no exceptions here, through again this notion of Logos – as we find in Plato’s Timaeus for example, or again in Pythagorean philosophy (the Tetractys), both of which are heavily laden with geometrical symbolism – symbolism that also managed to find its way into Christianity (presumably through the Gnostics) as reflected in the profound geometric symbolism that underpins the story of Jesus the fisherman and the net in the Gospel of John.

Furthermore, we find the ontological significance of love, Eros, buried right into the very core of both Aristotle’s and Plato’s theology, and cosmology. In each of these philosophical systems, it is love – again Eros – that is the motivating, or driving force as it were, that brings the universe into existence. In this sense, both Plato and Aristotle here reflect a much broader Hellenic cosmological tradition, one that is in fact rooted, and expressed, in the Theogony of Hesiod where Eros represents one of the primordial deities who participates in the very act of creation – what in the Orphic tradition is conceived of as Phanes, who emerges out of the great cosmic egg at the beginning of time from which the kosmos itself is created.

Love in fact, outside of its role in Plato and Aristotle’s theogony and cosmogony, plays a pivotal role in the philosophical system as a whole, providing one of the core, fundamental building blocks in each of their conceptions of virtue, as reflected more broadly in their systems of ethics – love as it were representing a very basic, and core, desire and motivating principle in man just as in God.[11]

So more generally then, in looking at the theology of Aristotle as it relates specifically to the theology of his predecessor and teacher Plato, we clearly find that the two differ fundamentally in terms of their overall epistemological and metaphysical framework, however Aristotle does not necessarily completely abandon Plato’s idealism entirely, even though ontologically speaking Aristotle treats the abstract concept of form, or idea, very differently than Plato, as a component of substantial form, but not as significant ontologically speaking as substance, or ousia – necessary but not sufficient as the case may be.

In Aristotle’s ontology, which very much rest at the heart of his theology, it is causality, and more specifically the notion of purpose, his final cause, from which the very necessity of the existence of an unmoved mover is deduced. It is only when applying his psychological theories (his theoretical framework for thinking as the apprehension of objects, which only when actualized come into existence) that Aristotle establishes – under the implicit assumption that man is fashioned in the image of God (or perhaps better put that God is a contemplative being just as man is) – that God in fact exists and that he is nothing other than the entirety of (eternal) existence itself.

[1] The Greek word that Aristotle uses is aitia, from Greek αἰτία, which is more accurately translated as “explanation” rather than “cause”. However, our terminology, for consistency sake, will follow the philosophical literature on the topic which refers to Aristotle’s theories related to aitia as causality, or more broadly Aristotle’s theory of causality. See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Four causes’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 29 June 2017, 12:28 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Four_causes&oldid=788094892> [accessed 8 November 2017].

[2] From the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Aristotle. Found at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle/.

[3] While Aristotle does not go so far as Plato as to put forth the notion of a full cosmological order based upon the “likely” existence of some intelligent creator upon which the Good or Best, as a divine, ideological ordering principle, serves as the underlying principle, or model, upon which the material universe is fashioned as he lays out in the Timaeus, Aristotle nonetheless does clearly indicate that from his perspective as well, what has come to be – reality – is so because of some reason, or set of reasons, i.e. causality, that not only determine the nature of that which comes into existence, but also bring said being into existence in the first place.

[4]Aristotle, Physics 194b23–35 as taken from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Aristotle at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle/.

[5] In the Greek, τέλος, or telos, for “end”, “purpose”, or “goal” is an end or purpose used in a philosophical sense as the end or purpose of a thing, the root of teleology as a philosophical pursuit.

[6] See Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Aristotle at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle/ pages 41-43 for a more detailed description of Aristotle’s view on the necessary and sufficient attributes of his four causal theory.

[7] It is however, very clear that Aristotle most definitely deviates from Plato’s view that the world of Forms is real and the world of the senses is simply illusory, which does in fact represent a significant divergence from Plato in his world view of reality akin to the dualistic view of reality in the Vedic philosophical tradition.

[8] Aristotle, Metaphysics Book XII, 1072a-1073a. Aristotle. Aristotle in 23 Volumes, Vols.17, 18, translated by Hugh Tredennick. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1933, 1989. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0052%3Abook%3D12%3Asection%3D1072b.

[9] Aristotle, Metaphysics Book XII, 1072a-1073a. Aristotle. Aristotle in 23 Volumes, Vols.17, 18, translated by Hugh Tredennick. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1933, 1989. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0052%3Abook%3D12%3Asection%3D1072b.

[10] Aristotle, Metaphysics Book XII, 1072a-1073a. Aristotle. Aristotle in 23 Volumes, Vols.17, 18, translated by Hugh Tredennick. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1933, 1989. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0052%3Abook%3D12%3Asection%3D1072b.

[11] Plato in particular delves into the nature of love, Eros, as reflected most poignantly in perhaps the Symposium, as well as in Lysis and to a lesser extent in the Phaedrus.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!