Into the Mystic: The Great Epistemological Divide

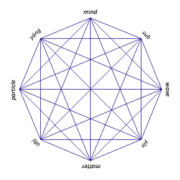

Upon reflection then, looking at the broader historical-cultural intellectual landscape in terms of how our worldview has evolved, at least in the West, since the advent of civilization in the 1st millennium BCE up until the modern era, the so-called Quantum Era within which we find ourselves, looking at the intellectual advancements, the revolutionary scientific and technological advancements that have led to post Enlightenment Era “progress”, it is worth noting that a perhaps unintended consequence of this advancement, this progression as it were, is that we have not only found ourselves almost stuck with an objective realist understanding of existence, of reality, but also at the same time have become very much siloed in terms of expertise and focus within the breadth of the intellectual landscape itself, within academia essentially. This is how academia has evolved since the Scientific Revolution in fact, how it has become structured in the modern era, again in the so-called Quantum Era where we find ourselves. Specific intellectual domains within academia – Physics, Psychology, Biology, Comparative Religion, or any of the Humanities for that matter – have become, as a matter of necessity arguably, so intrinsically complex that a) competency and mastery of one specific domain is almost at the exclusion of mastery of any of the other intellectual domains or disciplines, and b) cross-disciplinary research is not necessarily frowned upon per se but is certainly not encouraged primarily because advancement in a specific field, discipline or domain of study is a function of research and advancement only within that specific field or discipline.

This laser like focus by discipline – a fundamental characteristic of academia in the modern era, a characteristic that is reinforced by the initiation process itself within the Academy, i.e. the creation of independent research along with an associated dissertation where a student must break new ground in their discipline of choice in order to be granted entrance into the Academy, i.e. granted their PhD[1] – while no doubt serves its purpose in terms of preparing those who are to enter the Academy (academia) to ensure they are qualified to enter it, and speak for it at some level within the specific discipline within which they have been trained, and at the same time contribute to the overall body of knowledge within said domain, the Academy itself, has had the unintended consequence of discouraging, if not outright disallowing, academics to pursue theories along what we might call grander and more broader cross-disciplinary lines as well as arguably discourage the analysis and criticism of the intellectual assumptions and foundations upon which the Academy itself, in its modern conception, rests. In other words, there is no incentive for anyone pursuing a place within academia, pursuing their PhD, to question the very premise and authority, the very intellectual ground as it were, of the Academy itself. This is the reason for example, that Robert Pirsig, the author of the 1970s cult-classic Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance which did precisely that – i.e. call into question and attack the very intellectual foundations of the West as reflected by the teachings of the Academy – had to write, perform his research so to speak, outside of the confines of the Academy. He was expelled from it basically, out of which his ideas formulated, and which freed him in some sense to pursue the work.

In fact, Pirsig’s research, his insights if we may call them that, which initially began within the Academy as a University Professor in Bozeman Montana, effectively not only got him barred from the Academy, from teaching, but given the nature of his “epiphany”, driven by his search for the definition of the notion of Quality from which he divined was the source of hypotheses which underpinned the development and evolution of Science, in fact eventually got him institutionalized. It wasn’t until he renounced his so-called epiphany, after undergoing high and frequent doses of electrodynamic currents, effectively “fried” in a literally sense, after which he was finally declared “fixed”, after which be “safely” permitted back into society and could be rejoined with (what was left of) his family.[2] It wasn’t until many years later that he wrote of this intellectual journey, retracing his steps as it were, which is essentially the basic narrative of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance The point being here of course is that one can argue that illumination in and of itself, the discovery – or realization even – of intellectual or supra-intellectual paradigms is not only not encouraged within academia, it is actually specifically discouraged. While one can only theorize as to why this is the case, no doubt any intellectual framework upon which an entire socio-political structure is based and formulated – like the Academy in this case for example – is arguably not going to be very open to ideas which challenge the very foundations of its existence.

Interestingly, and again not surprisingly, despite the far-reaching influence of Pirsig’s philosophy, what he refers to as the Metaphysics of Quality, his teachings from either a philosophical perspective or intellectual perspective have yet to find themselves adopted in any sort mainstream way within academia, outside of a few classes in various Philosophy departments which focus on his work.[3] For very similar reasons arguably, at least one can surmise, academia barely incorporates Eastern theo-philosophical concepts outside of including Eastern philosophy as a general field of study within Comparative Religion departments necessarily. In fact, one can make the argument, that knowledge itself in the West, its boundaries and scope, which domains are to be included and which are excluded, is effectively defined by the curriculum of the Academy itself – the two almost self-supporting each other and reinforcing each other. And herein lies one of the biggest challenges from an intellectual perspective when looking to tackle some of the world’s biggest problems today, problems that as we mention to a large extent have an ideological basis – that is to say in order to provide a rational, intellectual framework that can cross the ideological chasm between the opposing worldviews between East and West as it were, it requires an almost wholesale revision, or at the very least a foundational reconstruction, of the very core of the Western intellectual foundation itself – as promoted, supported and reinforced by academia. Our concept of knowledge in and of itself must shift in order for us to even be in a position to solve some of these global challenges and problems – again a problem cannot be solved by the same level of consciousness that created it.

One can draw a parallel with this type of intellectual revolution if we may call it that, one that is only beginning right now as the Quantum Era begins to take hold of the collective psyche of humanity, crossing Eastern and Western boundaries, as Yoga and Tai chi (Tàijí) and alternative forms of medicinal practices and treatment (and by alternative we mean primarily Eastern methods such as Ayurveda, acupuncture, etc.) continue to proliferate in the West, there is a concurrent shift in worldview, an assimilation of sorts, that is happening. But it is worth noting that a) Yoga was first introduced in the West at the beginning of the 20th century so it’s been a long time coming in this regard and b) the institutions and body politic, if we may call it that, have reasons to resist the proliferation and spread of these ideas. Both from an economic perspective, as is the case with Health Care and Big Pharma companies who have a very large vested interest in the status quo and are in no way interested in supporting the proliferation of practices or techniques that, despite the fact that they may in fact have significant health benefits and/or be significantly cheaper than other forms of treatment, yet nonetheless represent a significant threat to their profit engines, or from a political or authoritarian perspective, as is the case with the Academy for example who also has an interest in preserving the status quo from an epistemological perspective.

The Enlightenment philosophers faced very similar challenges in a sense, except the authority that they were rebelling against was not intellectual or economical, but more political – as theological institutions in pre-Enlightenment times represented strong political forces as well, and arguably held just as much influence and power, as the political machines of nation-states in and of themselves. The Enlightenment philosophers, most notably of course Galileo and Copernicus, directly rebelled against the authority of the Church in the name of Science and Reason – risking not just exile and excommunication, from the Church as well as from the Universities that were very closely affiliated with theological institutions at the time, but in some cases – as was the case with Galileo for example, imprisonment.[4] Until eventually of course, as a result of the intellectual, social and political advancements and upheavals which ultimately characterize what we now refer to as the Scientific Revolution (circa end of 16th century to end of 17th), which was followed by the Enlightenment Era, or Age of Enlightenment (from circa the end of the 17th well into the 18th century) advancements in not just Science proper as we understand the discipline and field of study today but also socio-political revolutionary advancements that were driven by the Enlightenment Era philosophical achievements if we may call them that. Manifestations of these socio-political developments included for example the French Revolution in (1789-1799), the English Revolution (1688), as well as the American Revolution (1775-1783).

As a result, of course, not only did the socio-political landscape change forever, but the intellectual landscape did as well. Post Enlightenment, the fields of Religion and Science, which had been seen as closely related for centuries, if not millennia, prior, were now effectively split. Theology did not disappearing of course, but in terms of both political as well as intellectual influence, the sciences, and humanities, were now able to pursue their own goals independent of any influence from the Church. While perhaps to a much less drastic or lesser extent, the likes of Bohm, Everett and even Pirsig in the 20th century, with respect to their proposed ontological frameworks, their systems of metaphysics really, also attempted, arguably somewhat less successfully than their Enlightenment Era predecessors, to upend or invert the current prevailing (Western) ontological models which are so firmly entrenched in the Academy today. Specifically, we refer to not just the prevailing ontological framework of the West, again the notion of what constitutes reality, an intellectual paradigm which is rooted firmly in Classical Mechanics, but also the prevailing epistemological framework of the West, the boundaries of knowledge that are officially approved and designated by the Academy itself .

These scientists, Physicists most of them (with the exception of Pirsig who calls himself a philosophologer, or one who analyzes or studies philosophy), attempt to reframe the boundaries of and our understanding of reality, based upon not just Classical Mechanics but also upon Quantum Mechanics. And yet, despite their efforts, the models that these great minds put forth have nonetheless been effectively banished to the very deepest and least accessible corners of academia. In fact, one cannot even find non-orthodox, i.e. non “Copenhagen”, interpretations of Quantum Theory in standard text books on the subject – as if the implications of the Quantum Theory, and it’s now well proven set of axioms and principles which are fundamentally “non-Classical”, should have no bearing on our basic understanding of how the world works – be it at the quantum level or not (outside of certain philosophical circles, philosophy of science in particular, which is where one would have to look to find these respective theoretical models).

So to a certain extent, you can argue that these great thinkers of the 20th century, those that dared to attempt to integrate Quantum Theory’s fundamentally non-local and non-deterministic conception of at least the quantum realm into a more broad and encompassing ontological framework that didn’t necessarily reject the truth and validity of the so-called” Classical” view of universe – a reality that consisted solely of objects and observables moving through the continuum of spacetime, again what we call objective realism – but incorporated it into a more broad and encompassing intellectual, i.e. ontological, framework, have nonetheless been banished just the same. They were not excommunicated from some central religious or intellectual authority necessarily, or imprisoned like Galileo some 300 years ago now[5], but nonetheless banished in the sense that their ideas have in no way been accepted by academia and as such effectively live in the dark corners of the intellectual universe left for authors like myself, who is also not part of the Academy proper, to discover and write about, effectively relegating such teachings, such doctrines and theories, to the intellectual backwaters where a) you have to do your own, fairly rigorous, research to find them, and b) most if not all PhD program will not accept any further research in such non “mainstream” subjects in order to get accredited as a “Doctor of Philosophy”.

What we end up with, while most certainly better than where we were prior to the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment with respect to being able to freely pursue ideas and theories wherever they might take us, we have not nonetheless escaped entirely ontological or epistemological bias necessarily. The bias has just morphed from being theological or “religious”, into more intellectual or “Scientific, which again implies that anything “un-scientific” – like the realm of the Soul or its close intellectual and metaphysical corollaries like ethics or morality, or even the (potential) reality of higher states of consciousness – must be dealt with outside of academia, despite not just the relative importance of such topics, but the very ontological significance of such topics. This is the very reason for example, that Aristotle taught metaphysics, before Physics (meta in the Greek means “before” or “prior to”) and how metaphysics in fact came to be known, right up until after the Scientific Revolution in fact, for some two thousand years, as first philosophy. This would be just fine except that from an ontological perspective, the world of Science, the physical sciences in particular (Physics primarily) has become, whether intentionally or not, equated with our Western notion of reality – our objective realism again. That is to say, ontology – from a Western philosophical perspective which is where the term originated and therefore its specific domain of reference – is not just predisposed to an empirical and objective realist disposition, but it’s very intellectual foundations rest on these so-called “Scientific” presumptions. And therefore, as a byproduct of this way of thinking which is characteristically and uniquely “Western”, one whose intellectual origins at least can be traced back to the Scientific Revolution, our conception of reality, is at best limited at worst, ultimately flawed. This was the impetus of at least (some of) the work of David Bohm toward the end of his career, and the impetus of all of Robert Pirsig’s work.

This limitation perhaps manifests itself most clearly and prominently in the current gap, chasm even, and all sorts of attempts to bridge said gap, between Science and Religion for example. In the post Enlightenment Era intellectual paradigm in the West, that which is reflected most poignantly in academia, Religion has been relegated to the field of theology – literally the “study of” God, or gods as it were. It is in the domain of theology for example, where ethics and morality have effectively been relegated for the most part, outside of philosophical circles at least.[6] As a result of these hard lines that have been drawn between theology and Science, the Religion and Science intellectual chasm as it were, that we are effectively confronted with in the Western epistemological landscape, is that these “higher” states of consciousness which hold such ontological significance in the various mystical traditions throughout the world – in particular in the Eastern theo-philosophical traditions, many of which have been around for literally millennia and arguably are rooted, intellectually and theo-philosophically at least, into the heart of human civilization itself – cannot be integrated in any meaningful way into really any aspect of the prevailing Western intellectual paradigm, outside of theology itself – and even this domain of study is arguably lacking in terms of its acceptance, and integration, of mysticism.

These purported higher states of consciousness then, what in the East is viewed as a manifestation of the (most) true nature of reality itself, that which is most real you could say, ultimately defy not just definition (which the respective traditions within which these states are recognized would also concede for the most part), but also ultimately defy any sort of rational categorization whatsoever as established and promulgated by the full range of disciplines within academia, the presider over knowledge in the West. This holds true in fact even in the domain of Psychology where these mystics, if they were to be (and some have) subjected to modern day psychoanalytic methods or techniques, have been and are typically diagnosed with all sorts of psychotic disorders, a challenge outlined in some detail in a recent article in Scientific American in fact. [7] As already mentioned, Robert Pirsig himself was diagnosed as having a psychotic breakdown after he experienced what can arguably be called an altered, or “higher” state of consciousness or awareness that, because he himself as well as the people who he was surrounded by had no frame of reference for such experiences or states, led to him being institutionalized and subject to electroshock treatment to “dispel” this awareness from his being so to speak so that he could re-integrate back into “normal” society.

It’s this mystical experience really, at least how Pirsig describes it, that drove him to write – in an attempt to find the reason why our culture, i.e. the “West”, seemed to be so devoid of not just enthusiasm, but of values in and of themselves. This intellectual journey, where he literally and figuratively retraces his steps to that fateful day where Quality itself manifests directly and powerfully throughout his whole being to the point where he could not eat or function in any physical, or of course social, way, ends up leading to the formulation of what he calls a new metaphysics, i.e. his Metaphysics of Quality which is his intellectual solution to not only why we as a culture are devoid of values, but also in a sense also provides an intellectual bridge between Science and Religion by sidestepping theological questions entirely and yet affirming the existing of some sort of ground of existence from which what he calls “intuition”, i.e. hypotheses again, originate from. Of course this intellectual breakthrough that Pirsig had, given its complete divorce from, and abandonment of, any form of rational thought or any inclination toward social norms, stemming in no small measure from a direct communion with the source of Intellect itself, a total and compete comprehension of and absorption with of what he came to refer to as “Dynamic” Quality itself in its most pure and unadulterated form, led of course quite directly and efficiently to again him being institutionalized and thereby designated by society as a whole as “crazy”. Subsequently of course, even decades after his book and underlying philosophy has reached readers all across the world, his philosophy is still for the most part not accepted as a significant contribution to the intellectual landscape in the West, again academia.

It’s very difficult of course, given the author’s background in Eastern philosophy and mystical practices in general, to not look at the experience that Pirsig had as a direct experience of a very high state of consciousness, akin to the what the Indian theo-philosophical tradition in particular (i.e. Yoga) refers to as samādhi, what the Buddhists refer to as nirvana, and what we refer to throughout as supraconsciousness. Of course, as any seasoned practitioner of the mystical arts will tell you, and what Pirsig unfortunately had to find out (quite painfully) on his own, is that the experience of these higher states of consciousness, some of which can be induced by various means, methods and techniques should a) be done under the guidance of a competent teacher, and b) should be practiced in conjunction with various moral and ethical precepts and conjunctions, and c) hopefully if direct realization of the Absolute is in fact realized, you have the good fortune of not being immediately checked into a mental institution. Despite the fact that this event, this experience of Pirsig’s, had all the hallmark characteristics of true “mystical” experience, there existed no intellectual or social, or even psychological in fact, foundation for the rest of society, or even his family or friends for that matter, to interpret or understand this experience in any way – how he got there, what he was in fact experiencing, or perhaps better put what experience he had in fact lost himself in. Furthermore, Pirsig himself, nor again those around him or close to him, had at their disposal any tools or techniques, any methods whatsoever, to facilitate “bringing him back” to a normal state of consciousness so to speak, to the normal physical plane of existence within which all typically live and exist in (all non-mystics at least).[8] As a result, as mentioned previously and perhaps not surprisingly, Pirsig was subsequently institutionalized and diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, and then during an extended stay in this facility that was designed for those who were unable to live in society, so-called “psychotics”, in order to “fix” him and rid him of his “psychotic” tendencies, where he was treated with, among other things, extensive electroconvulsive therapy. [9]

If we look to the Eastern philosophical traditions however, there is no such relegation of experience, no matter what state or level of consciousness we speak of, to the back seat of “empirical reality”, the very foundation of the objective realist worldview which underpins not just virtually the entire epistemological landscape of the West, but the ontological landscape as well – Psychology included we may add. In the Indian theo-philosophical tradition in particular however, this couldn’t be further from the truth. What we refer throughout as supraconsciousness for example, a term we use In order to try and provide some intellectual, primarily psychological (Freudian), frame of reference for the experience, is not so much an “experience” (a term that in and of itself presumes an objective realist ontology) but more a state of being, where a larger, or higher, state of consciousness “manifests” around or within an individual persona, or psyche, at a given point in the spacetime continuum, using standard 20th century Physicist jargon.

It is for this reason for example, that the term mysticism had to be manufactured in the West, coming into prominence in Comparative Religious circles in the last few decades or so, in order to provide at least some sort of intellectual foundation, as well as terminology, for something – really again some state of awareness or consciousness – that defies any sort of rational or intellectual description, something that is arguably not irrational necessarily but, to coin a term, supra-rational. Mysticism then, as a term in and of itself that sat outside the intellectual semantic landscape, provides a nice clean and neat, intellectual, box to place not just the Eastern theo-philosophical systems that recognized the verity and ontological significance of these higher states of awareness, or again consciousness, but also the aboriginal and shaman like practices that anthropologists and comparative religious scholars had encountered all throughout the world – each of them encountering these experiences within dozens if not hundreds of distinct sociological and theological environments, and yet at the same time recognizing that all of these experiences shared many commonalities and therefore were inherently mystical. The discipline of mysticism then, the sub domain within Comparative Religion really, was established to discuss and explore these states of consciousness in a rationally coherent, and in classical Western modes in contrast and comparison to each other and to the classic Western worldview, i.e. again objective realism in order to (attempt to) provide some sort of frame of reference for what the Eastern theo-philosophical traditions at least consider to be the very ground of reality itself for thousands of years.

Again, in virtually all of these so-called “mystical” traditions, the experience which we have come to know or understand as intrinsically mystical – in the Western sense that this term is understood as something distinct from “every day” experience and which, by definition really, defies any sort of rational explanation definition, or description – is described in the various traditions as a sort of communion with a higher state of being or some sort of expanded form of consciousness. As such, given that it clearly expresses an idea, or again an experience, which exists beyond any type of objective realist conception of reality, it therefore is beyond any sort of intellectual framework that can be conceived by the mind, the mind in this sense representing an entirely intellectual construct which is considered to be, primarily again according to the Eastern theo-philosophical (mystical) traditions more or less, subservient to, or perhaps better put a lower order manifestation of, the mystical experience itself.

This does not mean however that the mystical experience, the state of expanded consciousness or awareness, or again what we call supraconsciousness, which represent such an integral and fundamental component of the metaphysical and ontological landscape of Eastern theo-philosophy in general and in particular the Indian theo-philosophical tradition, is not described or articulated in any way, shape or form. It, in fact, in these various traditions is associated with certain epithets and assigned various terms or expressions that reflect the true import and weight of the experience, and in turn reflect the ontological, and theological, significance of, the state of consciousness or being which, at least again according to the Eastern theo-philosophical traditions in particular, is accessible to, or perhaps better put the true essence of, each and every one of us. This is what the Indian theo-philosophical notion of Satcitānanda represents, as well as what Brahman from an anthropomorphic theo-philosophical perspective at least, also represents. We also find for example, a very extensive and detailed terminology set forth in the Yoga Sūtras, where not only are the specific practices to elicit such higher states of consciousness outlined in detail, but also the higher state of consciousness itself, i.e. samādhi, is also referred to and explained in some detail as well, even if by analogy and metaphor only.

A consequence of our distinctly Western, reductionist and somewhat restrictive worldview, with its respective underlying epistemological assumptions upon which it is constructed, is that since it effectively relies and depends upon Science as a discipline for discerning not just truth from fiction, but also the boundaries of what can actually be defined as well (empiricism), we end with a fairly restricted conception of knowledge and reality, one that holds the physical realm, the realm of the senses, as more ontologically significant than the psychological, or inner, world. This is juxtaposed of course, with the Eastern, again primarily Indian, epistemological frameworks which not only do not restrict the notion of reality only to the physical world or realm, but also include an epistemological landscape which distinguishes directly between forms of knowledge across the sensory spectrum, psychological and supra-sensory included.

Where this leaves us from a Western epistemological standpoint at least, is that since these so-called “higher” states of consciousness are, by nature “subjective” and lack empirical verifiability, and as such most certainly cannot be considered as reflective of, or even hinting of, any sort of inclusion in our definition of reality, from an empirical perspective of course, they are excluded from the epistemological landscape itself. And a byproduct of this epistemological exclusion, these topics are effectively left out of academia proper, with the exception perhaps of again some very unique and rare Comparative Religion, or perhaps Anthropology courses which may touch on mysticism, or its corollary shamanism, as a purely intellectual endeavor. And yet this notion of the (potential) existence of higher states of consciousness or awareness, again supraconsciousness, is in fact true and real from an epistemological perspective, i.e. fundamentally real, which of course is one of the core principles and beliefs of virtually all of the Indian theo-philosophical schools and traditions, would effectively stand our current (Western) conception of reality, one entirely devoid of not just theology but even spirituality, entirely on its head – quite literally almost.

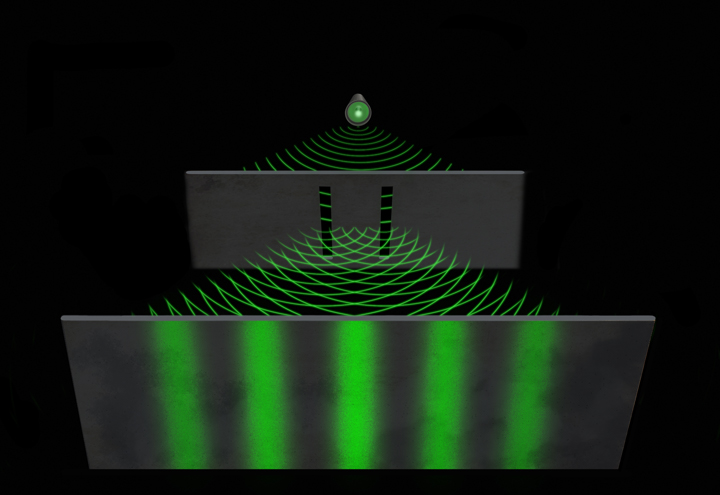

Nowhere else is this quite restrictive, empiricist and causally deterministic, classically Western, ontological worldview, manifest its ontological limitations as in the Standard, aka “Copenhagen”, Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics , where some of the very fundamental premises regarding the nature of the reality underlying the model, the quantum observables as they are sometimes called – specifically the principles of entanglement and locality – sit in stark opposition to the prevailing understanding of how the world basically works, i.e. our Western conception of reality which is based upon fundamental principles (assumptions) such as causal determinism, locality and objective realism, i.e. the foundations of Classical Mechanics. And yet despite this, outside of some fancy mathematical gymnastics that have been employed to try and explain Quantum Mechanics in a fully deterministic framework, i.e. the now quite popular many-worlds interpretation of Quantum Theory, the idea that the true nature of reality, of existence itself, might not be truly causally deterministic, or even objective in any real sense of the term, is literally beyond comprehension. It breaks the model, quite literally.

And yet these Eastern theo-philosophical traditions, in particular again the Indian theo-philosophical tradition, have been grounded since inception upon the premise of the ontological superiority of consciousness, or awareness, over objective reality. This has been the case since the very dawn of their respective civilizations within which the theo-philosophical systems themselves emerged, perhaps the very reason why these belief systems persist, a worldview where different levels or domains of knowledge, as a theo-philosophical concept, can co-exist and at the same time not contradict each other. What we find in the Indian theo-philosophical tradition in particular, arguably one of its defining features in fact, is that the conception of knowledge, the underlying epistemological framework, not only fully integrates what we in the West have now split into the separate and distinct domains which we call “Religion” and “Science”, but also integrates the notion of, the fundamental truth of, higher states of consciousness, that exist in a very real sense above or beyond “physical” reality as a higher order dimension of sorts from which physical reality emerges or manifests.

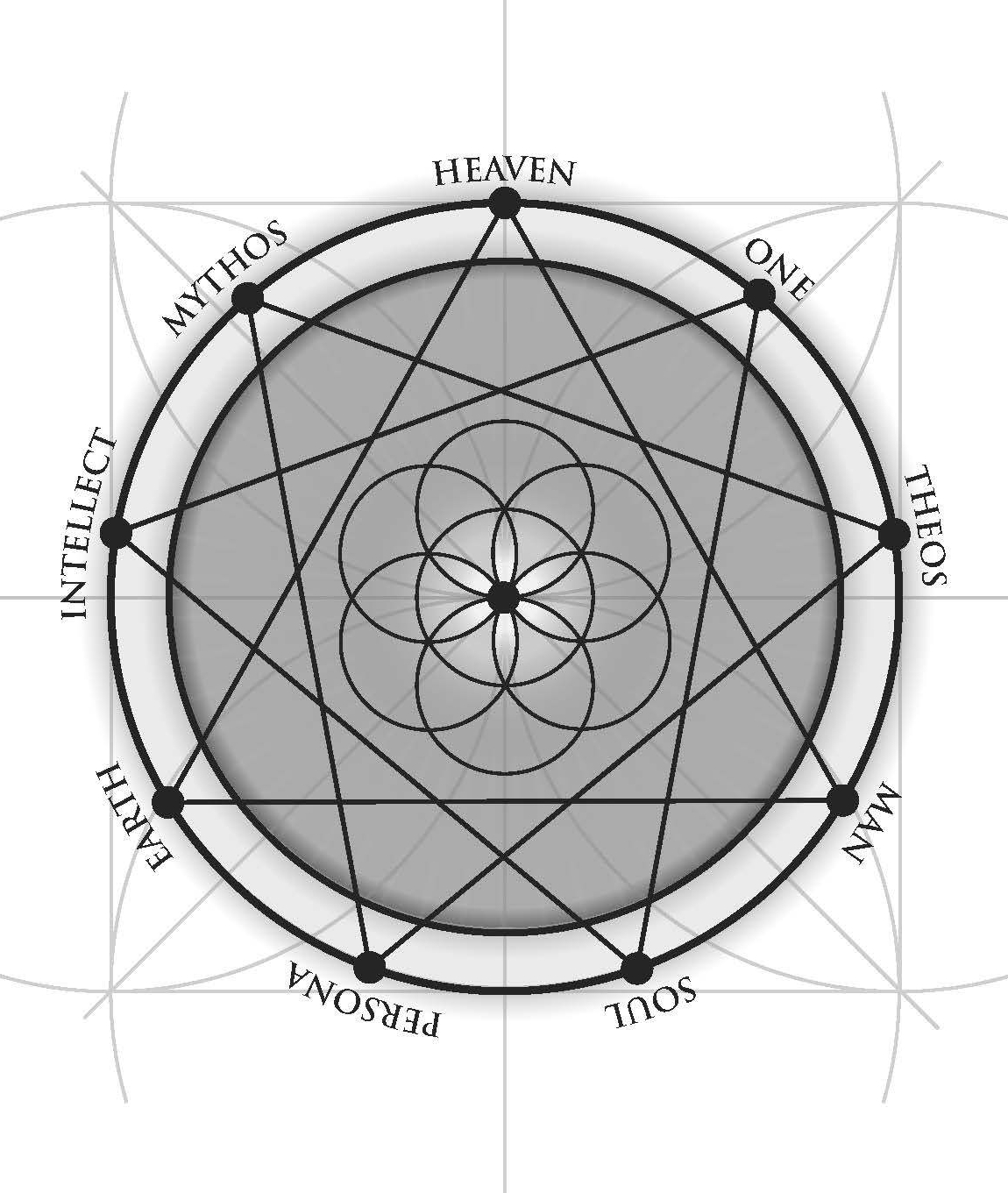

By so doing, the theo-philosophical system effectively subsumes subject-object metaphysics into their conception of reality, i.e. their ontology, as well as into their epistemological framework, i.e. their concept of knowledge in toto, while at the same time not sacrificing the notion of physical reality, and the associative underlying predictive and technological power of empiricism or objective realism in and of themselves as integral parts, components, of the entire ontological framework as it were. This is accomplished quite elegantly, by distinguishing between higher and lower forms of knowledge. The former being classified and understood as existing above or beyond our basic cognitive or intellectual capabilities, and the latter being defined as being bound directly by such intellectual capabilities, the realm of the senses as it were – what in the West is the domain of Science. This epistemological framework in fact, is one of the marked characteristics of the Indian philosophical tradition, which not only allows for a much more broad conception of knowledge generally speaking, one which incorporates and integrates the mystical experience into it (defined again by such terms as Satcitānanda or Brahman, constructs which tie more or less directly into the underlying mythological tradition from which they emerge) but also lower forms of knowledge as well which govern not only the world of natural phenomenon but also sociological phenomena such as ethics, morality and of course the world of name and form within which we as individuals are ultimately bound to and by.

The Indian theo-philosophical tradition provides these various metaphysical frameworks, epistemological frameworks really, within which all forms of knowledge, both higher and lower forms, can be understood in relation to each other and can be understood within the context of the entire domain of human knowledge of experience which again includes the mystical domain, the physical domain, as well as the sociological and psychological domains.[10] In a sense this epistemological framework is much more closely aligned with Aristotle, in its breadth and scope as well ontology, rather than the epistemological framework of the West in the modern era which again rests upon the very often overlooked, and definitely underestimated, metaphysical assumptions of objective realism and empiricism. Nonetheless, in this classically “Eastern” worldview, one which is by nature not reductionist or empirical, we find this expanded intellectual, epistemological, paradigm that incorporates what we are calling higher, i.e. mystical, forms of knowledge, which correlate directly to what we are calling supraconsciousness which in turn is the most ontologically significant principle in these so-called “mystical” traditions. These higher states of awareness, or again higher states of consciousness, are considered to be verifiable truths within these (mystical) theo-philosophical traditions in the sense that a) the experiences themselves can be confirmed by other advanced practitioners of these mystical arts, i.e. mystics or spiritual “adepts”, b) the experiences conform to the underlying theo-philosophical texts which describe these mystical states in some detail, and c) that the lasting effects of the mystical experience are also verified against the theo-philosophical literature and tradition as well, effects such as moral fortitude, compassion, sympathy for others, and other classically “religious” attributes or qualities.[11]

Regardless, in these very ancient belief systems, one’s that existed not only prior to monotheistic theology, but also clearly pre-date civilization itself (in the West or East) we find that the necessary qualification of the worldview as “mystical” is not only not necessary, but redundant in a way because the theo-philosophical system reflects the underlying worldview of the people and culture within which it emerged which is intrinsically mystical you could say. And in this “Eastern” worldview, which retains and is reflective of an ontological paradigm that is arguably almost a complete inversion of the predominant intellectual paradigm in the West, these lower forms of knowledge are not abandoned for these higher forms (as is the case in the standard Western intellectual paradigms where the truth of these supraconscious states is rejected on purely Scientific grounds, i.e. the states in and of themselves are purely “subjective” and as such are “unverifiable”) but are viewed as complimentary and supportive of, the basic underlying ground of reality itself – a reality that is closer to what we in the West like to refer to as consciousness or (pure) awareness than it is “objective” in any way. Using David Bohm’s construct of implicate and explicate orders from which his grand ontology is constructed, terms, these mystical states simply reflect a higher order reality from which the physical and mental world emerge from as no less true, and yet lower, forms of order or structure – explicate order domains that manifest from a higher, implicit, order which is fundamentally mystical in nature.

[1] Philosophiae Doctor or Doctor of Philosophy, or PhD, which incidentally betrays its heritage and origins as to the original conception of philosophy as put forth by the ancient Hellenes, or Greeks – Aristotle in particular. That is to say, as a corollary for science (sciencia)in a broader sense, and in the sense of how it was viewed in antiquity, i.e. philosophia.

[2] Robert Pirsig (1928-2017) published just two books, the first of which was a cult classic of sorts and a best seller initially published in 974, entitled Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values and his second work, much less popular and yet in Pirsig’s eyes at least much more profound from a philosophical perspective, was entitled Lila: an Inquiry into Morals which was initially published in 1991.

[3] One of which the author actually took within the Philosophy department at Stonybrook University in the Summer of 1993 incidentally.

[4] Galileo’s heliocentric theories which were deemed heretical in 1616 and he was sentenced to prison in 1633 for the same where he spent the remaining years of his life until 1642.

[5] Although you could argue that Bohm’s exile from America in the late 1940s under suspicion of being “communist” does not differ all that much from the exile of some of the early Enlightenment philosophers for some of their work.

[6] Enlightenment Era philosophers made various valiant, and arguably quite successful attempts to bridge this gap and include ethics and morality, as well as God, within various intellectual frameworks that were not theological, or religious, per se – very much in the spirit of the first philosophers, or Aristotle at least. Kant is probably the most notable of these, his work representing to most the very height of Enlightenment philosophy. It is in fact in the works of Kant that the term “Enlightenment Era” comes from.

[7] For a good outline of the challenges distinguishing between higher states of consciousness and mental illness generally, see the article published in Scientific American in December 2016 by Nathaniel P. Morris entitled “How Do You Distinguish between Religious Fervor and Mental Illness” which can be found at https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/mind-guest-blog/how-do-you-distinguish-between-religious-fervor-and-mental-illness/.

[8] If we look at the life of Ramakrishna for example, who was surrounded by people who were trained in the art of mystical techniques and practices, there are many well documented incidents of not only him experiencing such states of what he described as “divine ecstasy”, but also of his friends and fellow “mystic” practitioners using certain words or phrases, whispering them in his ear, to “bring him down”, or “back” to the “physical” or normal plane of existence.

[9] Parts of the episode are documented in at least some cursory fashion toward the end of his first book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Some details, all of which are fairly well known and Pirsig himself has been pretty open about, can be found on his Wikipedia page at: See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Robert M. Pirsig’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 10 September 2017, 22:32 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Robert_M._Pirsig&oldid=799972066> [accessed 24 October 2017].

[10] Depending upon the Indian philosophical tradition of course, “higher” and “lower” forms of knowledge are given relative degrees of importance. So in Advaita Vedānta, i.e. the non-dualistic or monistic form of Vedānta, it is the higher form of knowledge that is not only given greater significance, but the lower form of knowledge is denoted as “unreal” or “illusory”, i.e. Maya. In the other forms of (orthodox) Indian theo-philosophy, these lower forms of knowledge are given more inherent realistic value, as is represented by what is considered to be the qualified non-dualistic interpretation of Vedānta referred to as Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta, or in the dualistic conception of Vedānta referred to as Dvaita Vedānta.

[11] This last category becomes even more important and relevant with respect to “verification” when the very highest of spiritual states or consciousness are in question, what is described in the Upanishadic literature as Satcitānanda, or Existence-Knowledge-Bliss-Absolute, or in the Yogic literature as samādhi.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!