The Gnostics: Jesus as the Revealed Logos

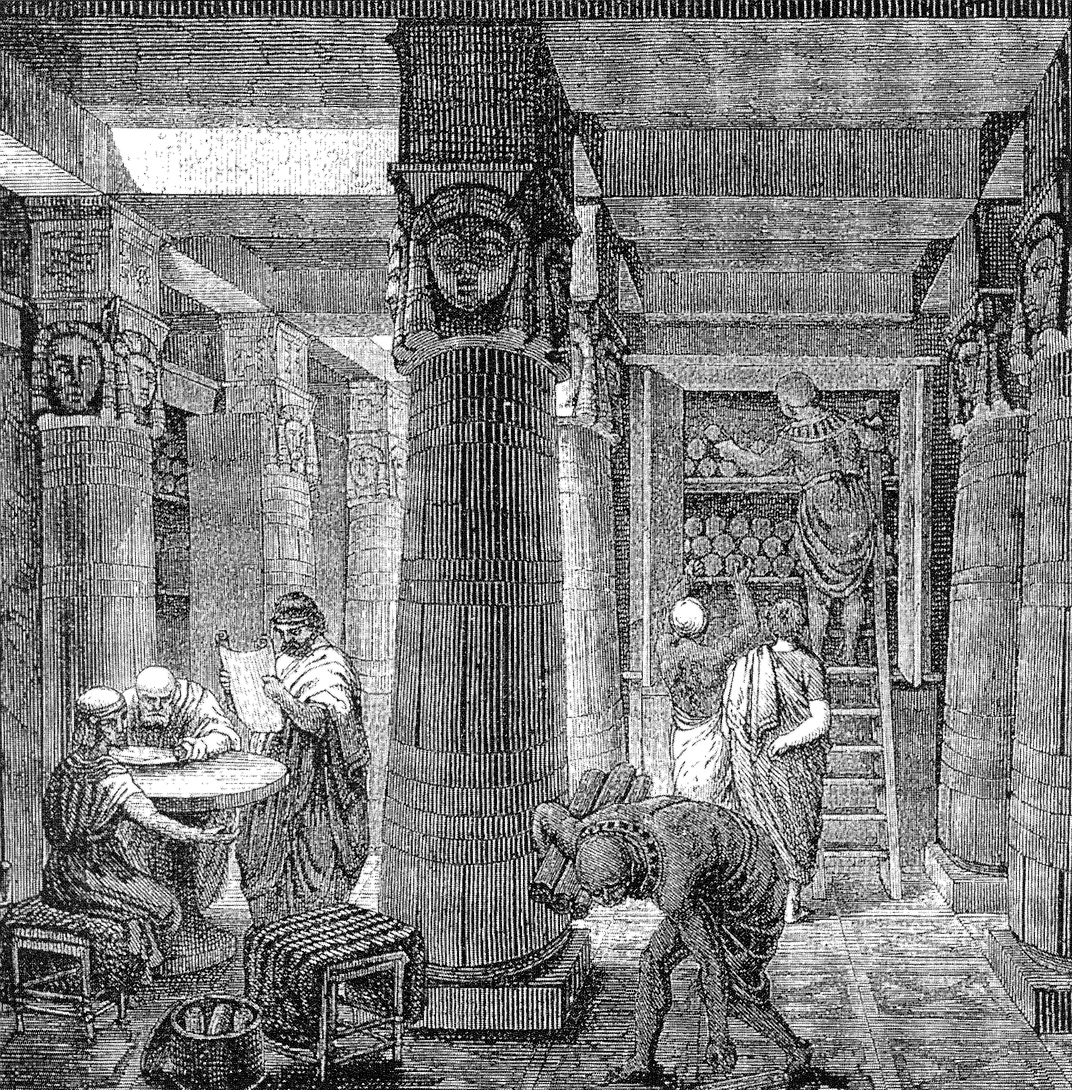

In contrast to what we would consider the more orthodox interpretation of Jesus through the doctrine of Logos, and incorporating the Wisdom tradition of the Jews at the same time, we find another influential Gnostic teacher who comes from the academic and intellectual milieu of Alexandria, namely Valentinus (c. 100 – 160 CE). Although born and educated in Northern Egypt and Alexandria, Valentinus spends his most productive years teaching in Rome and at one point, according to Tertullian, was considered for the position of the Bishop of Rome but started his own group after he was passed over.

Although none of Valentinus’s writings are extant, we know of the popularity of his school (Valentinianism) as well as many of its tenets and beliefs from Clement of Alexandria, who writes that Valentinus was a follower of Theudas and that Theudas in turn was a follower of St. Paul, from the early Christian theologian and apologist Irenaeus (c. early 2nd century – 202 CE) whose best known work, Against Heresies (c. 180), is a five volume work of which only fragments of the supposedly original Greek text exists but a full Latin version is extant which defends (what has come down to us as) orthodox Christianity against the various so-called heretic Gnostic schools that were prevalent at the time, with a special emphasis on the school started by Valentinus and the Gospel of Truth:

But the followers of Valentinus, putting away all fear, bring forward their own compositions and boast that they have more Gospels than really exist. Indeed their audacity has gone so far that they entitle their recent composition the Gospel of Truth, though it agrees in nothing with the Gospels of the apostles, and so no Gospel of theirs is free from blasphemy. For if what they produce is the Gospel of Truth, and is different from those the apostles handed down to us, those who care to can learn how it can be show from the Scriptures themselves that [then] what is handed down from the apostles is not the Gospel of Truth.[1]

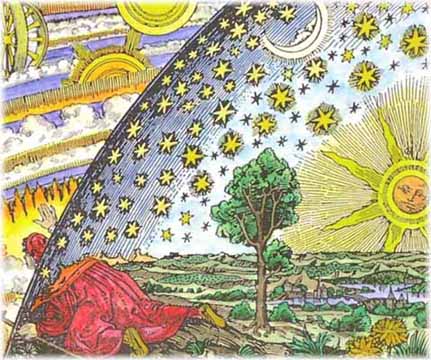

The copy of the Gospel of Truth, which Irenaeus refers to explicitly in his Against Heresies and is attributed to the Valentinian School, was discovered in the Nag Hammadi Library collection in the second half of the twentieth century and is believed to have been authored in the middle of the second century CE, in Greek. In this Gospel, the life and tribulations of Jesus are not called out specifically as they are in the four canonical Gospels, and instead there is a focus on the creation of the known universe in error (in personified form), and the delivery of Jesus (a messiah) to the earth to show us eternal life – to (re)establish the wisdom of gnosis, “knowledge”, which in itself grants salvation. This salvation, this blessing of eternal rest, comes to those who have experienced “gnosis”, a transcendental state of awareness where the object of worship “knowledge” is merged entirely in the worshipper. The gnostic tradition no doubt, for all intents and purposes reflects a deep esoteric and mystical teaching that was said to have come straight from the master (Jesus) himself – the “secret” teaching. This was the pinnacle state of Plato the mystic, where the man once bound in the cave to perceive shadows, is released from his prison and shown the true divine realm which was illuminated by the Sun, of which the images in the cave were but shadows.

The Gnostics were true mystics, but faithful to the worship of Jesus in their own way, not in his physical form as having been born in the flesh, liberated oneself, and then was crucified in the flesh by Pontius Pilot, but his message of immortality. He was Logos personified, and in that sense he could never have been born, every present since the beginning of time. This idea of the dichotomy of God the father and Jesus the Son, which theologically speaking is the most radical notion that we find in the Gospels themselves, and the very reason why he was put to death in the first place (he refused to admit otherwise). But to the Gnostics, in contrast to the as of yet germinated orthodox interpretation of Jesus’s life, with a focus on the life of the flesh, it was what Jesus taught was inside of all of us, our birthright in fact, if we could just merge ourselves into knowledge itself – the blessed Gnostic. The philosophy shared some Platonic features as well to be sure, for it was the existence of the One, Being itself, that the Gnostic could truly know. Logos was still the key, the connecting force and principle that bound the eternal cosmos to the individual Soul, in whose image it was created.

The metaphysics behind Gnosticism, despite being poorly documented given the mystical and esoteric nature of the movement, nonetheless must have sat on a sound Peripatetic and Platonic foundation, but Plato’s hidden mysticism was drawn out and put at the forefront of the message, for it was Plato’s Good and Same, his Being and Becoming, his One, that could upon constant contemplation and reflection could be fathomed, and in so fathoming one could become One, and the Indefinite Dyad could cease to Be. The world of Forms and Ideas whose penultimate source and final end was the Good, the Sun of gnosis in outside of Plato’s cave, through which the shadow of the greatest and perhaps most brutal of persecutions could be seen as the greatest salvation for mankind.

That is the gospel of him whom they seek, which he has revealed to the perfect through the mercies of the Father as the hidden mystery, Jesus the Christ. Through him he enlightened those who were in darkness because of forgetfulness. He enlightened them and gave them a path. And that path is the truth which he taught them. For this reason error was angry with him, so it persecuted him. It was distressed by him, so it made him powerless. He was nailed to a cross. He became a fruit of the knowledge of the Father. He did not, however, destroy them because they ate of it. He rather caused those who ate of it to be joyful because of this discovery.[2]

But to the Gnostics the manifestation of the eternal Logos in the flesh meant that there was an element of imperfection in the universe, at least from our lowly perspective. Christ was the consort of Sophia, our Jewish wisdom goddess who was associated with the Isis, the savior, of Egypt. It was the tradition of Wisdom, and the vengeful God of the Jews that the Gnostics could not recognize as the state of universal affairs. And in so doing, they associated Yahweh with the Demiurge of Plato, who thought he mastered and created the whole universe but in fact there was another layer of heavens and gods above him, from which Sophia and Christ emerge, and in so doing rectify the erred and flawed condition of the universe of man. Sophia and Christ her consort is the mythology that is created to explain the possibility that the Logos of God could actually appear in the flesh. Their conception of Jesus as the Word in the flesh was established to provide the theological bridge between world of men and the world of God which had been drawn asunder since mankind was cast out of the Garden.

This was the rift between the orthodox interpretations of Christ and Gnosticism. Leaving the mystical bent of the Gnostic tradition aside, which in and of itself threatened the emerging authoritarian structure of the Church, there was still a major theological divergence, from a cosmological perspective, that it spoke to major rifts in the two seemingly compatible faiths. There were two seemingly juxtaposed interpretations of the message of Christ in the centuries that followed his death – the one orthodox view that his life, in its divine character, its extraordinary and miraculous beyond belief story line, was in itself his message. And his life should be worshipped, and sanctified and celebrated. And to accommodate this they needed a Father, a Son, and a Holy Spirit which moved the waters at the beginning of time itself, must be of the same “substance”, of the same nature, undivided and ontologically equivalent and yet different manifestations of the great unified force of the undivided One, hence the doctrine of the Trinity which has come down to us. The Gnostic view looked more upon his life not as existing actually but took more of an esoteric and mystical vantage point, where the Christ was not actually born and did not die but in fact lived eternally as a manifestation of the Logos.

Another Gnostic classified teacher from Alexandria around this time was Basilides who flourished from approximately 117 to 138 CE, a contemporary of Valentinus, whose teachings he must have been exposed to at least some extent, as well as Justin Martyr whose life was spent further to the East somewhat outside of Alexandrian influence. He claimed to have inherited his teachings from the apostle Matthew, is known to have been one of the first commentators on the Gospels (entitled Exegetica) – although his work exists only in fragments and quotations from detractors unfortunately – and is also known for having developed a cosmology and world order that differed quite significantly, at least according to Irenaeus, from the majority of the other “Gnostic” traditions. His teachings must have been popular however for it is said that his followers, known as Basilidians, persisted for at least two centuries after his death in Alexandria.

The Christian philosopher Basilides of Alexandria (fl. 132-135 CE) developed a cosmology and cosmogony quite distinct from the Sophia myth of classical Gnosticism, and also reinterpreted key Christian concepts by way of the popular Stoic philosophy of the era. Basilides began his system with a “primal octet” consisting of the “unengendered parent” or Father; Intellect (nous); the “ordering principle” or “Word” (logos); “prudence” (phronêsis); Wisdom (sophia); Power (dunamis) (Irenaeus, Against Heresies 1.24.3, in Layton, The Gnostic Scriptures 1987) and “justice” and “peace” (Basilides, Fragment A, Layton). Through the union of Wisdom and Power, a group of angelic rulers came into existence, and from these rulers a total of 365 heavens or aeons were generated (Irenaeus 1.24.3). Each heaven had its own chief ruler (arkhôn), and numerous lesser angels. The final heaven, which Basilides claimed is the realm of matter in which we all dwell, was said by him to be ruled by “the god of the Jews,” who favored the Jewish nation over all others, and so caused all manner of strife for the nations that came into contact with them—as well as for the Jewish people themselves. This behavior caused the rulers of the other 364 heavens to oppose the god of the Jews, and to send a savior, Jesus Christ, from the highest realm of the Father, to rescue the human beings who are struggling under the yoke of this jealous god (Irenaeus 1.24.4). Since the realm of matter is the sole provenance of this spiteful god, Basilides finds nothing of value in it, and states that “salvation belongs only to the soul; the body is by nature corruptible” (Irenaeus 1.24.5). He even goes so far as to declare, contra Christian orthodoxy, that Christ’s death on the cross was only apparent, and did not actually occur “in the flesh” (Irenaeus 1.24.4)—this doctrine came to be called docetism.[3]

But this somewhat superficial reading of Christ’s message had deeper levels of meaning to the Gnostic community, a community which also boasted close lineage to the Apostles themselves – Valentinus to St. Paul and Basilides to Matthew. Both these early Gnostic teachers were from Alexandria of course, and their doctrines focused less on the physical life and death of Christ but the eternal message that lied within his secret teachings. This was a mystic uprising, one that had many heads and many variations in practice, but they were at the least united on Christ as the consort of Sophia, and that it was the flawed Demiurge who needed to be bailed out of his self-created predicament by Christ the savior. But their worship of the prophet was consistent, but they disagreed on how his message was to be carried on. To the Gnostics, and even to Clement of Alexandria (among others such as Irenaeus most notably) who spoke against them, it was Jesus who was the new song for the new age. They just disagreed on the song itself, but their tune was not altogether different. The message spoke of eternal life, and Christ’s role in granting it to all of mankind, but how Christ fit into the eternal celestial and cosmological structure that underpinned creation itself, well this was a major theological divide between the two early competing interpretations, if one could simplify the various schools under two separate banners, of the message of Jesus of Nazareth.

The Gospel of Thomas, one of the other great finds in the Nag Hammadi Library collection of scrolls, is non-canonical, and contains what are thought to be quite early sayings and teachings of Christ, much of the material being found in the canonical Gospels pointing to either a common source of all of the material or perhaps to the earlier origins of the Gospel of Thomas work, or to the existence of an even earlier source, a source given the code name “Q” from which the Gospel of Thomas and the synoptic Gospels drew on heavily. The latter view is probably the most dominant one amongst early Biblical scholars, that is the existence of an earlier source Q from which all these Gospels drew, but it is also believed that perhaps the Gospel of Thomas had ties with Syria where sentiment for Thomas was strong.

The Gospel itself is composed of 114 sayings which are attributed to Jesus, almost half of which strongly resemble similar passages in the canonical Gospels, the others being of perhaps more Gnostic origin as they are not found in any of the canonical Gospels. In all likelihood however, it does appear that the Gospel of Thomas, although categorized as Gnostic given its exclusion from standard biblical canon and its existence in the Nag Hammadi Library texts which at some level define what we now refer to as Gnostic literature, does represent a valid and very close connected tradition to the teachings of Jesus himself, and this Gospel, like the majority of the other Gnostic texts, does not emphasize the great prophet’s death and resurrection and its meaning for the salvation of mankind, but on the notion of the knowledge which he revealed to his followers, hidden in secret teachings and rituals which the masses could not understand or comprehend – a notion that clearly found few proponents in the early Christian Church Fathers.

Jesus saw some babies nursing. He said to his disciples, “These nursing babies are like those who enter the (Father’s) kingdom.”

They said to him, “Then shall we enter the (Father’s) kingdom as babies?”

Jesus said to them, “When you make the two into one, and when you make the inner like the outer and the outer like the inner, and the upper like the lower, and when you make male and female into a single one, so that the male will not be male nor the female be female, when you make eyes in place of an eye, a hand in place of a hand, a foot in place of a foot, an image in place of an image, then you will enter [the kingdom].[4]

The theme of the Gospel of Thomas runs from esoteric teachings of inner, hidden knowledge as evidenced from the quotation above, but reference to a variety of other parables some of which are also found in the canonical Gospels, speaking to the validity of the tradition represented by the Gospel of Thomas as well as the varying interpretations of the message of the historical Jesus that existed in the few centuries after his death. In this gospel, Jesus’s divinity is not explicitly referred to, nor is the story of his death by crucifixion or resurrection from the dead, the theme of the Gospel is the “hidden words that the living Jesus spoke and Didymos Judas Thomas wrote down”, as is stated in the introduction, the hidden and secret nature of the teaching lended itself to Gnostic classification, and clearly it circulated in Gnostic like esoteric and mystical communities as evidenced by it being found in the Nag Hammadi Library, which also contained an excerpt from Plato’s Republic mind you.

Another Gnostic classified text which is worth mentioning is the so-called the Apocryphon of John from the second century CE (it was known to Irenaeus and mentioned in his Against Heresies) which survives in four extant manuscripts in varying lengths, three of which were found in the Nag Hammadi Library, and narrates an alternative story of creation which can only be looked at as an attempt to the synthesize the Demiurge of Plato, the Yahweh of the Jews and the one true God the Father that Jesus speaks of in some sort of coherent story line. The cosmological account describes the single unified and eternal principle of the Monad from which all creation comes forth and from which the Aeons emerge, Light (which is synonymous with Christ) and Mind being some of the basic constituents of the early creation and from which further Aeons and powers are created. Eventually one of these Aeons, Sophia, without consent of the Monad and without the aid of a male companion brings forth an entity named Yaltabaoth, who is the first of a series of fallible and less that purely divine heavenly creatures called Archons and from which our heavenly and earthly creation is formed and from which salvation, via Christ, is required in order that eternal life and balance to the universe be restored.

The Pistis Sophia, a Gnostic text of somewhat later origin from maybe the third or fourth century CE, relates the gnostic teachings of Jesus to his disciples after he is resurrected from the dead, alluding to period of 11 years that he taught his disciples after his death by crucifixion. In this text Sophia also plays a prominent role and is associated as the consort of Christ, the revealer of mysteries, the Heavenly Mother, the Psyche of the world and even as the female aspect of Logos. The Pistis Sophia describes the highest realm of the light, the nature and subsistence of souls after death, and the way of salvation through initiation into the mysteries of Christ. This book quotes from Psalms, from prophets of the Old Testament, as well as from some of the canonical Gospels and despite its Gnostic bent retains some of the core Christian theological features that survived in the orthodox Christian theology, with an altogether esoteric and mystery cultish bent consistent with the Gnostic sects and schools of thought from which it must have emerged.

Although it’s hard to sum up and categorize the position of the various Gnostic sects which from a certain vantage point sat in opposition to the more orthodox interpretations of Christian theology as espoused in the Epistles of Paul and the canonical Gospels of Mathew, Mark, Luke and John, it is clear that this tradition represented some sort of threat to the growing power of the Christian authority which chose to focus less on his “mystery” and “secret doctrine” and more on his birth, teachings and resurrection as relayed in the canonical Gospels, and the reliance on his words as captured therein that spoke to Christ the savior as being the only gateway to heaven.

According to the Gnostics, this world, the material cosmos, is the result of a primordial error on the part of a supra-cosmic, supremely divine being, usually called Sophia (Wisdom) or simply the Logos. This being is described as the final emanation of a divine hierarchy, called the Plêrôma or “Fullness,” at the head of which resides the supreme God, the One beyond Being. The error of Sophia, which is usually identified as a reckless desire to know the transcendent God, leads to the hypostatization of her desire in the form of a semi-divine and essentially ignorant creature known as the Demiurge (Greek: dêmiourgos, “craftsman”), or Ialdabaoth [Yaltabaoth], who is responsible for the formation of the material cosmos. This act of craftsmanship is actually an imitation of the realm of the Pleroma, but the Demiurge is ignorant of this, and hubristically declares himself the only existing God. At this point, the Gnostic revisionary critique of the Hebrew Scriptures begins, as well as the general rejection of this world as a product of error and ignorance, and the positing of a higher world, to which the human soul will eventually return. However, when all is said and done, one finds that the error of Sophia and the begetting of the inferior cosmos are occurrences that follow a certain law of necessity, and that the so-called “dualism” of the divine and the earthly is really a reflection and expression of the defining tension that constitutes the being of humanity—the human being.[5]

[1] Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 3.11.9. Quotation from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gospel_of_Truth.

[2] Gospel of Truth, translation by Robert M. Grant. From http://gnosis.org/naghamm/got.html.

[3] Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry for Gnosticism. http://www.iep.utm.edu/gnostic/

[4] Gospel of Thomas, verse 22. Translation by Stephen Patterson and Marvin Meyer, from http://gnosis.org/naghamm/gosthom.html.

[5] Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Gnosticism. http://www.iep.utm.edu/gnostic/

by Leon Van Kraayenburg

by Leon Van Kraayenburg

Everything is very open with a clear explanation of the issues.

It was definitely informative. Your website is useful.

Thanks for sharing!