The View from the West: The History of Objective Realism

The East-West division with respect to worldviews and ways of thinking clearly has significant limits in interpretative utility despite its proliferation and widespread use in the academic and intellectual community, in the West in particular. Having said that it is fair to say that the “Western worldview” is perhaps best characterized by reductionism and an almost obsessive focus on the that which can be “known” which rests on fundamentally materialistic and deterministic assumptions, i.e. what we call in modern philosophical circles as empiricism, which in turn sit upon on a fundamental belief in the supremacy of the physical world over the mental or theological world, and rest primarily on rules of logic and reason, and causality, as the principle tenets for how reality itself is defined. The East in contrast can be said to view the world much more holistically, or perhaps better put has inherent in it a more comprehensive and expansive view of reality as the manifestation of phenomena, which includes the psychological domain from which deeper meanings of reality can be grasped as much as they are graspable intellectually.

While any definition excludes certain criteria that may be of value in the domain being discussed, this delineation, definition and distinction of worldviews serves as well as any other with respect to drawing the lines between the two ends of the intellectual spectrum as it were of modern thought, a distinction that clearly goes beyond any geographical boundary at this point, but one which nonetheless has significant implications on how “reality” is defined and perceived. This contrast in modes of thinking about the world around us today in many respects resembles the metaphysical debates that arose between Plato and Aristotle in the Hellenic world in the 4th century BCE which provided the metaphysical and intellectual basis for the development of all of Hellenic philosophy for some thousand years. To Plato, forms (eidôs), or ideas (ιδέες), were the fundamental building blocks of reality. With Aristotle, this solution was inadequate or incomplete. To Aristotle, reality primarily consisted of substance, but also rested on the notion of form, albeit in the context of Aristotle’s ontology, form played a much less significant role than it did in Plato’s.

In Aristotle’s philosophy, the known universe consisted of things, or more accurately beings, that were primarily defined by the notion of substantial form, a hylomorphic construct where being, or substance (ousia) is a compound of matter as well as its underlying form. This he combined with a fairly comprehensive view of causality, which included all of the physical as well as mental aspects of a “thing” which underlie its “existence”, purpose being included as one of the components of causality. Aristotle’s theory of existence, his being qua being, eventually evolved to provide the intellectual basis of causal determinism which underlies modern Science (Physics) as we understand it today.[1]

To Plato the forms, shapes or ideas, which manifested, were required even, to produce and define what we think of as “physical reality” so to speak were ontologically superior to the physical things themselves. These physical “things” could not exist, would have no definition or existence at all, without the underlying forms which made them what they are. This is essentially Plato’s theory of forms as we have come to understand it today, as perhaps best illustrated in his Allegory of the Cave story in the Republic where individuals are chained to the floor in a cave with a roaring fire in back of them that they cannot see, mistaking the shadows that are displayed on the wall in front of them which are merely reflections of objects passing behind them but in front of the fire as “real” things, having no knowledge of true objective reality until and unless they are “released” from their bondage and led up onto land where the sun reigns supreme and true physical reality is shown to them in all its glory.[2]

Aristotle’s view eventually won out of course in the West from an intellectual perspective but Plato’s idealism persists in religious, really theological, and (some) philosophical intellectual circles, as juxtaposed with the fundamental tenets of say science, physics, and biology – the modern pillars of science. We now however live in a world permeated by East/West synthesis and interaction and we can find many of the hallmarks of that ancient debate present within the scientific, philosophical and religious communities throughout the world today – for example the Creationists versus the Evolutionists where strict interpretative lenses are applied to ancient myths which clearly were crafted before any notion of modern science even existed.

Even though culturally speaking this East-West divide may no longer have any geographical boundary upon which it rests given how international a community we live in now, it does nonetheless reflect the division between contrasting worldviews that can be loosely aligned with the “scientific” versus “spiritual” worldview – i.e. the worlds of Science and Religion respectively. Perhaps another look may reveal that the two approaches need not sit in contrast with one another however, and if integrated into a larger whole can be looked at as two sides of the same coin. But what is missed by most it would appear is that there is no right or wrong worldview but in fact that the coin simply has two sides – speaking quite directly to the deeper knowledge that may rest in the power of the Yīn-Yáng intellectual framework, the integration and balancing of opposites, within which reality is viewed, at least in antiquity, in the Far East.

One way to classify and distinguish between the Western and Eastern worldviews, contrasting them from a cosmological and physical universe perspective, is that of a ‘closed’, or ‘bound’ view of physical reality versus an ‘open’, ‘cyclical’ or ‘process’ based reality. The former view is a hallmark of Western cosmological mythology and has continued to be a hallmark of Western intellectual development ever since. It permeates Western philosophical inquiry to a large extent and continues to be one of the defining characteristics of Western thought even today. Scientific development, from its first method of philosophical inquiry by the ancient Greeks straight through the more modern “Scientific Revolution” and even into the modern “Quantum” era has looked at the world primarily through a mechanistic and systematic lens, an analysis and modeling of these ‘closed’ systems and how the various components of these well-defined, ‘bound’ systems interact with each other and are described from a phenomenological, i.e. objective realist, perspective.

Western intellectual developments in this context can be looked at this quest for understanding the fundamental and most elemental characteristics of matter and the objective world, and in turn the relationships between these objects of perception. Quantum Theory represents the ultimate end of this line of inquiry though, the final boundary upon which the limits of this type of worldview, this idea of ‘closed’ systems of objective reality, can be defined without the aspect of cognition, the role of the observer, included in the model per se. This worldview, while not wrong or incorrect in any way, is primarily physical and objective, and leans heavily on the mathematical laws and theories which have been “discovered”, which govern the behavior of these “things”. All of these things being capable of objective description and whose states are ultimately defined by one or more physical, and measurable, properties. Things that can be said to exist within the system in question – be it a set of atomic data within the context of a quantum experiment or a set of interplanetary or galactic objects that are viewed within the context of the “known” or “visible” universe as a whole – are ultimately defined and “bound” by the underlying mathematical laws as well as the measurable qualities or characteristics that these laws are designed to yield.

In fact the boundaries of the entire system itself as defined from a “Western” worldview, is what we call the “Universe” or “Cosmos”. This notion is defined as every “thing” that has existed or will exist within this physical and objective conception of reality since the beginning of “time”. Time itself, what the Greeks referred to as Chronos, is created as part of the cosmological universal order as part of the creation of the universe itself. Time and the Cosmos (kosmos) are in fact co-eternal and co-existent. While we defer to all of the advancements of modern science which point to a single, massive “singularity” which occurred some 13.8 billion years ago[3]. This is the universal creation event that we refer to as the Big Bang Theory which marks the primordial event after which all cosmological and theoretical physical study is concerned with and represents the beginning of not just “time” itself, but also the creation of the physical laws that govern “our” universe.

The very roots of these boundaries of space and time and the cosmos itself can be found in the ancient mythological narratives of our predecessors in the West, whether we give credit to our intellectual ancestors or not. In fact, to think beyond these boundaries, before the great singularity event from which our universe emerged, or even to look beyond the known (really “visible”) universe is not considered even a conceivable act of study from a physics or scientific perspective. Once someone leaves these boundaries, they in effect have left the boundaries of (Western) Science itself, and have entered into the realm of philosophical speculation or inquiry, i.e. non-empirically testable or verifiable theories or ideas which provide the “boundaries” of Science itself.

The view from the East however – as seen through the eyes of Vedānta, Buddhism and Chinese philosophy for example – can be characterized as “cyclical”, “process-oriented” or “open”. Open in the sense that the universe itself is not considered to have a beginning per se, but is believed to be eternally existent and always and forever manifesting as an “experiential” event that is not simply defined by the definition of physical objects which exist in time and space, but is a constant unfolding of “experience” which cognitive beings partake in and ultimately provide the basis for any understanding of “it” – it being “reality”. This distinctive characteristic of the East is evident in the Hindu belief in the cycles or “Ages”, or Yugas, of time that defines the cosmological worldview of the Hindus (and was embedded in early Greco-Roman mythos as well in fact), and is reflected – from an anthropomorphic and mythical perspective – by the inbreathing and outbreathing of Brahman.

In the “East”, speculation about the universal order of things and our place in it is viewed within this cyclical, or “unbound” context, not within a set physical boundary in time or space per se. This is why attempts to classify the ancient mythos of the Chinese almost defy definition from a Western intellectual perspective. The idea of “Cosmos” in fact, as defined by the boundaries of space and time within which the physical universe that we live in was “created” and will ultimately be “destroyed”, does not exist. Their view, most predominantly reflected in the Yìjīng, is one of a continuing process of becoming and change within which any sort of meaning, meaning which fundamentally includes and synthesizes not just the “person” who is looking for this meaning, but also the underlying socio-political context within which this individual “co-exists”. The physical aspect of the universe is not, and effectively cannot, be distinguished from the “being” who is participating in the continual process of change and becoming which is constantly unfolding. This is what we mean by an “open”, or essentially “unbound” worldview.

In order to find this source of this “closed” view of the West, this almost obsession to break things apart and drill further and further into the constituent components of a thing until once can literally go no further, one needs to reach back to the beginning of development of thought, and language, in the West. To the ancient Greeks who laid down the intellectual foundations – linguistic, metaphysical and otherwise – that we have inherited in the West through language and culture down through the ages. One can look at the beginning of this “bound” and “closed” systemic view of the world as having its roots in Pythagorean philosophy, a philosophy that as we understand it rested on the harmony and eternal co-existence of numbers and their relationship to each other, forming the underlying ground of all existence. It is from the Pythagorean tradition as we understand it, that Plato’s fascination with geometry – as reflected most readily in perhaps his most lasting and influential dialogues the Timaeus – was founded.[4]

To truly understand the context, source and origins of Western thought, we must of course reach back to classical Greek philosophical development, from which our definition of philosophy in the West rests, we must first understand the intellectual (and socio-political) context within which these great and lasting influential thinkers emerged, and how and why this transition from mythic poetry and divine worship as the primary source of knowledge becomes relegated and subservient to philosophy, a term first coined by Pythagoras in fact according to historical tradition. By philosophy here, we again use a primarily Western definition which is almost recursively defined as the purely rational and intellectual pursuit of knowledge itself as reflected in the classic philosophical tradition within which these intellectual developments evolved. Philosophy in this context can also be defined more specifically and literally being by looking at the meaning of the word itself in Greek from which it is derived, i.e. the “love” or “study of” “knowledge” or “wisdom”, i.e. sophia.[5]

While the intellectual and academic tradition has typically divided philosophical and theological development into “Western” and “Eastern” branches, some scholars have challenged this classical distinction, in particular in the last few decades as linguistic, genetic and archeological evidence has pointed to a more complex and interwoven evolution that took place in the Mediterranean, Near East and Indian subcontinent in classical antiquity. In this region, starting in the latter part of the 4th millennium BCE or so, we find evidence for perhaps the greatest invention in mankind’s history – namely writing.

At this juncture in human history we find not only the beginnings of hieroglyphic script in Northern Africa (Egypt) from this time but also the introduction of cuneiform script in the Near East (Mesopotamia). Both systems no doubt started as pictograms and logograms, symbols that represented abstract thoughts or ideas, but each eventually evolved into more complex writing systems that contained what linguists refer to as morphemes, graphemes and phonemes, essentially smaller units of meaning which came to represent sounds and words alongside symbols and ideas. It is this development more so than any other that ushered in the era of human evolution that is characterized by advanced abstract thought, an invention that was arguably not only required in order to support advanced civilization in the respective cultures within which it evolved, but also at the same time supported and underpinned said developments.

For as we find evidence for these various systems of writing and they became more prevalent and widespread, the civilizations that utilized this invention at the same time became more urbanized and specialized, allowing and supporting the establishment of a “priestly” or “scholarly” class of individuals that eventually formed the social and intellectual basis for not just trade and commerce, but eventually the basis for all theo-philosophical development as well, even if we do not find true “philosophical” works form these regions until the first millennium BCE or so. Necessity is indeed the mother of invention and writing is certainly no exception to this universal rule.

These writing systems had to adapt and evolve to support not just barter and trade (basic mathematics), but also contracts and agreements between individuals and states, as well as – and this is perhaps a later development (3rd and 2nd millennium BCE) to codify and capture various rituals and ceremonies which had been established to appease the gods, a shared cultural and theological phenomenon that we find all through Eurasia in antiquity in fact. [Egyptian hieroglyphs associated with burial grounds (Pyramid Texts), cuneiform tablets with various myths and tales of the gods (the Enûma Eliš), the divination tools and symbols developed by the ancient Chinese (the Zhōu Yì), the Indo-Aryan Vedas and the Indo-Iranian Avesta literature, etc.].

Another core characteristic of these ancient writing systems is that given that many different languages were spoken even in the specific geographic regions themselves (the Near East/Persia, North Africa and Egypt, ancient China, etc.), these writing systems had to evolve to support all of these different (spoken) languages as well. It is this feature, this requirement as it were, that in no small measure drove the evolution of these first archaic hieroglyphic and pictogram writing systems into their more modern alphabetic form. For example, we have evidence that cuneiform in particular was adapted to support a wide variety of ancient languages of the Middle and Near East such as Akkadian, Elamite, Hittite, and Hurrian among others, languages from both the Afroasiatic branch of the linguistic tree as well as languages from the Indo-European branch.[6]

It is with cuneiform script that we find then – via its direct descendant writing system referred to as the Phoenician alphabet for which we find evidence in the first half of the first millennium BCE – what is commonly held to be the parent writing system of virtually all the alphabetic systems of writing in antiquity that were used not only throughout the Mediterranean but also in the Middle and Near East as well as the Indian subcontinent. For the Phoenician alphabet is held to be not only the parent system of the ancient Greek alphabet (and in turn Latin of course which evolved from a form of the Greek alphabet), but also the ancient Aramaic alphabet from which ancient Hebrew alphabet is believed to have derived, Pahlavi which is the script used to write many of the ancient Iranian and Persian languages (e.g. the Avesta), and even the various forms of the Brāhmī alphabetic script that we find in use throughout South and Central Asia in the latter part of the first millennium BCE which, in its various descendant forms, is the script used for the transcription of the ancient Sanskrit Vedic literature.[7]

So again in the West, which includes in this context the Indian subcontinent which we have shown reflects the “Indo-European” theo-philosophical mindset more or less, we can actual follow the progression in written history of this transition from more archaic and pre-historical forms of divine worship, i.e. mythos, to the practice and discipline of philosophy as a practical art upon which the rational foundations of ethics, morality, and the common good rest, i.e. Logos. In the Hellenic world, which is what modern historians and academics look to as the basic building blocks of “Western” thought, this transition takes place in the first half of the first millennium BCE from the time of Homer and Hesiod, through the developments of the so-called “Pre-Socratics” (as we understand their views primarily through fragments from later authors and interpreters of their beliefs) and ultimately to the works of Plato and Aristotle which form the basis of Hellenic philosophy in all its forms.

It is then with this historical and evolutionary context in mind, we can see how it is that the Hellenic philosophical tradition has come to be so representative of “Western” thought, one which is characterized by the study and analysis of reality as a series of bound or closed systems in time and space and one which even God himself is seen as bound within said intellectual framework. He is the Creator. Prior to creation, God himself does not exist in fact. It is this intellectual framework which not only ultimately leads to the establishment of Science in the modern era, but also one which provides the rational underpinnings for theology, i.e. Religion, as well – as the both the early Christian Church Fathers as well as the early Islamic/Arabic philosophers (falṣafa), all appealed to the Hellenic philosophy in one form or another to provide a rational foundation for their theological views.[8]

It was not until the Scientific Revolution some 1500 years later that intellectual thought breaks free of religious dogma, and while the basic principles laid down by the ancient Greeks which established the Truth of the Biblical narrative were for the most part altogether abandoned, at least from a physics perspective, later philosophers and the first scientists in fact remained nonetheless convinced of the underlying geometric foundation of the universe as the ultimate expression of God. None of these great thinkers were atheists in any sense of the word and although they may have rejected most, if not all of the basic tenets of the Church, especially with respect to Creation mythology as laid out in Genesis (at least from a literal standpoint), the still held onto the firm belief that mathematics, and in turn geometry, represented the ultimate and best expression of the divine in the material world.

Even to the Enlightenment Era philosophers, mathematics and geometry were the core basic building blocks of universe from which our natural world can be understood. Newton rested his grand three laws of motion, which underpin Classical Mechanics even today, upon Euclidean geometry which described physical space in terms of spatial coordinates on a three dimensional plane as well as their movement through time via a new method of mathematics called calculus which facilitates the calculation of the rates of change of objects and the slope of their respective curves in Euclidean three dimensional space (differential calculus) as well as the calculation of the areas under and between these curvatures (integral calculus). Using these tools, along with his universal law of gravitation, Newton was able to more accurately predict the orbits of the planets around the sun – as first put forth by Copernicus – as well as establish the firm mathematical, and of course fundamental geometrical, ground for Physics which is still taught in schools today. This system that he created, which rested on his three laws of motion that described the interaction between objects within Euclidean geometrical space, were the cornerstones of Physics until the twentieth century when Einstein upended Physics with his Theory of Relativity.

Relativity, as Einstein “discovered” it, expands upon the three dimensional notion of space put forth first by Euclid and leveraged by Newton, and established a new geometrical fabric of reality based upon the notion of curved spacetime, fully integrating gravity into the geometrical framework (as the bending, or curvature of spacetime) rather than it being described as an external “force” acting on objects across space and time as Newton did. Einstein was required to create – or perhaps better stated “borrow” – a new and more complex geometrical framework within which the fabric of spacetime, its underlying curvature, as well as the objects moving within it could be described. It is within the framework of General Relativity that his famed equivalence of mass and energy is yielded (E = mc2), where the overall system is bound by, and fundamentally constrained by, the constant limit of the speed of light no matter what an observer’s frame of reference is.[9]

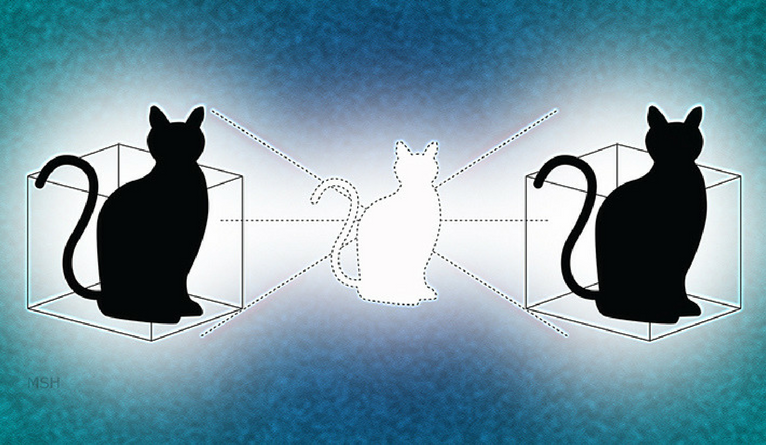

Quantum Mechanics is no exception either. Despite the theory calling into question our basic understanding of what an “object” truly is and how it can be defined independent of its “environment”, calling into question our basic conception of objective reality in and of itself, a new geometrical framework needed to be established in order to describe the movement of these so-called objects, or “particles”, at the sub-atomic scale, i.e. Hilbert space, a generalization of Euclidean space which extends vector algebra and calculus to support any number (an infinite number in fact) of “spatial” dimensions. But of course, the underlying geometry of Quantum Mechanics, despite its predictive power, comes with its some very intriguing and “mysterious” mathematical certainties which call into question some of the foundational principles of Classical Mechanics, mainly the notion of locality as it relates to objective phenomena.

Leaving aside the fundamental inconsistencies and philosophical questions that Quantum Mechanics poses to the underlying assumptions and beliefs that underpin Classical Mechanics (in particular with respect to the notions of causal objective determinism and objective realism and its sister principle locality), regardless both “physical” models are understood and described within the context of bound, closed intellectual frameworks and systems. In other words, each model of reality – both Newtonian Mechanics as well its more abstract cousin which includes the notion of gravity, i.e. General Relativity, as well as Quantum Theory – describes reality as a physical system which includes objects, things, which interact with each other and exist and are describable within specific quantifiable and measurable physical states at specific moments in the spacetime continuum. Furthermore, these models have the power to predict the behavior, or future states, of these various things or objects using various sophisticated geometrical models and equations that in toto, with known starting variables such as positon, momentum/velocity, mass, etc., can predict the movement of the these objects through the Euclidean geometrical space within which these objects are said to exist via the use of sophisticated mathematical calculations and equations that operate on, and yield results within, these complex geometrical structures which are presumed to “represent” reality.

This is essentially the power of modern science, the ability to predict future states of phenomena given a set of starting variables, all measured and quantified within the context of an observer. What’s lost in all of this power and complex mathematics however is that it all rests upon a very specific set of assumptions and principles regarding reality itself, i.e. the mathematics and related theories bound the definition of reality – what in philosophical circles they call ontology. Such is the reason now doubt that many of the greatest minds of the twentieth century who understood Quantum Theory better than any of us refused to enter into any metaphysical interpolation of the theory itself, not just on philosophical grounds but on basic mathematical grounds – in short calling into question the ability for mathematics, and of course geometry to which it is intrinsically related, to provide and sort of meaning to reality from a philosophical and metaphysical perspective.

Such is the nature of Physics as it stands today, both when studied at the grand scale as governed by the laws of General Relativity “discovered” by Einstein as well as Quantum Mechanics, as put forth and articulated by the likes of Bohr, Heisenberg, Schrödinger, de Broglie and others in the twentieth century. Nonetheless this undying and unfailing belief that the natural world is best understood through the lens of mathematical laws and formulas which govern the various states and relationships of the “physical” world as it moves through a specifically described and formulated geometric continuum, reality in fact as we have defined it, is a belief shared by and first promulgated by the ancient philosophers from the Mediterranean starting with Democritus, Pythagoras, Plato and Aristotle among others and has carried forward into the 21st century. The problem comes when, to borrow a phrase from Robert Pirsig, we confuse the map with the territory.

[1] For a more detailed look at Plato and Aristotle’s epistemological and cosmological views, see Philosophy in Antiquity: The Greeks. Lambert Academic publishing, 2015. By this same author. Chapters on Plato and Aristotle respectively.

[2] A loose analogy can be drawn between the differing ontological views of Plato and Aristotle and the Daoists (Daojiā) and Confucianists (Rújiā) of ancient China, where the Daoists in many respects align to the idealism of Plato while the Confucianists, while not outright denying the existence of the ideals (the supreme of which is the Dao itself, corresponding in many respects to the Platonic Good), appeal to custom, ritual and ancestral worship as the harbinger of that which is right. One could perhaps best categorize them as “realists” to oppose the Daoist idealism rather than the more materialistic bent of Aristotle.

[3] According to modern cosmological theories, i.e. Big Bang Theory, the physical universe came into “being” some 13.8 billion years ago in a massive explosion which not only created everything in the physical universe, but also spacetime itself as well as provided the basis for the physical laws that govern said universe. For details on the underlying theories and resulting calculations see Wikipedia contributors, ‘Big Bang’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 11 December 2016, 14:55 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Big_Bang&oldid=754229288> [accessed 11 December 2016].

[4] For a more detailed look at Pythagorean philosophy please see https://snowconesdiaries.com/2014/08/23/pythagorean-theology-truth-in-numbers/.

[5] Philosophy from the two Greek root words for “love”, i.e. philo, and “wisdom” or sophia, the latter term being the same root word that was used to describe the “Sophists”, a group of teachers in classical Greek antiquity that Plato in particular took great pains to distinguish himself from.

[6] In Egypt, the hieroglyphic writing system primarily evolved hand in hand with various forms of the Egyptian language, languages that are placed in the Afroasiatic language family. From the ancient hieroglyphs, various forms of script developed, hieratic being the most influential which was associated by the Greeks with the class of priests who used the script (derives from the Greek phrase (used first by Clement of Alexandria) grammata hieratika, literally “priestly writing”. [Hence the connotation of the word hieratic as meaning “of or related to sacred persons or offices”. See Wikipedia contributors, ‘Hieratic’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 11 September 2016, 02:13 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hieratic&oldid=738788563> [accessed 11 September 2016].

[7] Direct descendence of Brāhmī script from the Phoenician alphabet is disputed by many scholars but the similarities nonetheless abound, and the time period of its inception corresponds very neatly into what we know of the spread of Near Eastern culture into the Indian subcontinent by the various Assyrian and then Persian empires which dominated the Near East and the Indian subcontinent part of the world in the late second millennium BCE into the middle of the first millennium BCE, making at the very least a very close relationship, if not an altogether direct descendant relationship, likely. For detail, see Wikipedia contributors, ‘Brāhmī script’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 7 November 2016, 06:42 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Brahmi_script&oldid=748252726> [accessed 7 November 2016]

[8] The early Christian Church Fathers looked to Plato’s Timaeus perhaps more than any other ancient Hellenic philosophical work for the intellectual and rational foundations for their creation mythology that we see in the Old Testament, a work which of course the Christians wholeheartedly adopted as their own. For example, we find in the extant works of Philo Judaeus, Clement of Alexandria, Origen and St. Augustine various attempts to construct and rationalize “Judeo-Christian” theological doctrine on top of the fundamental Hellenic philosophical intellectual systems that came before them.

[9] The mathematics used to support General Relativity falls under the heading of differential geometry. Within this framework Einstein leveraged Riemann curvature tensors, specifically a 4-dimensional Lorentzian manifold of signature (3, 1) or equivalently (1, 3) to model the movement of objects within a spacetime continuum.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!