On Science, Physics and Knowledge (excerpt from IRA)

We seemed to have reached a place in the human understanding where Physics, the intellectual (really academic) discipline of the description of the world of matter, and Psychology, the intellectual discipline of the world of mind, are on a sort of collision course of integrated understanding the likes of which have not been witnessed since ancient times, where the most if not all of the prevailing worldviews considered the realm of the mind, or the world of spirit, to be not the same as the physical world, the world of matter, but nonetheless very much related to it and in a sense fundamental to its existence.

At the root of all the major theological and philosophical traditions (and even the minor ones), you find this sort of gray, fuzzy distinction between the realm of mind and the world of matter. In most cases, if not all, these worlds are bridged by a sort of third, correlated and more fundamental principle upon which both the mind and the world are predicated. That human beings as part of Nature rather than separate from it. This is in fact where the word physics comes from, from the Greek physis which means Nature.

In the Native American tradition for example, we find the all-knowing and ever-present Great Spirit who not only sits atop all of creation, but within it as well. The Great Spirit as they understood him was the Judeo-Christian God (the Holy Spirit and the Father), but the Son as a gatekeeper for Heaven was not included of course. The Stoic’s thought the universe was alive, that it was infused with spirit, or pneuma (Valdez 2014b), an idea we find in China with the notion of qi (or chi) which represents the vital life force, breath again, that dwells within us and throughout the universe upon which life itself (and health ultimately) depends (Valdez 2016). This idea is found in the Yogic traditions in India as well with the notion of prana, or life force, which courses through our physical bodies (chakras) and provides a sort of pathway to the infinite (Valdez 2019).

This is a very old idea, that we are a part of the universe and are connected to it in a very fundamental way, and it is not until much later that this split between mind and matter, subject and object, becomes the prevalent worldview, really the signatory principle that comes out of the Enlightenment where theology (religion) is supplanted by science for good. Descartes is typically blamed for the split you could say, as sort of the father of Western mind-body dualism (cogito ergo sum), but it is with this classic bifurcation from which the great floodgates of Western Science opened leading to breakthrough after breakthrough of technological advancements that have led us to a place where you can read the words I type on a page today, digitally at your desk or home office tomorrow.

But the Eastern philosophical traditions primarily (e.g., Buddhism, Vedanta, Yoga, and Daoism to a lesser extent perhaps), kept this idea alive, as the mystery cults of ancient Greece and Rome had done for centuries, and as many if not all of the African, American and Australian aborigine traditions hold to even today, that the Creator was not just a theoretical idea, a metaphysical construct or a rational deduction that must exist in order for the cosmos to exist – as Aristotle, perhaps the father of materialism argued with his so-called unmoved mover – but an actual living being, or entity, that we ourselves, through the practice of certain spiritual practices and techniques, or through the ritualistic use of hallucinogenic plants or herbs, could commune with and experience in very real way.

It is fair to ask, perhaps our obligation to ask, whether this truth can be verified, can we trust it to be true? And if we are to consider such questions, by what criteria should we approach such subjects that did not bear the same degree of let’s say objective reality than say the momentum or velocity of a football screaming through the air on Lambeau Field (from a certain relative frame of reference of course). For it is these types of questions, or at least the searching for the answers of these types of questions, from which our understanding of the world, and ultimately our place, our purpose, within it, has even a chance of being properly understood.

This type of engagement with life, engagement with the world you might say, this postmodern world filled with division and skepticism and perhaps most remarkably, no God, as Nietzsche so famously proclaimed first in Gay Science (1882) and then most infamously in Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1885):

God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us? What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?

The problem with the end of Physics is that it ultimately hits a sort of objective realism barrier at the Planck scale, the scale at which Relativity breaks down and we are confronted with a new paradigm of not just Physics, but of measurement itself. At this level of reality we are forced to confront the idea of meaning directly, thrusting us back into the very world of philosophy that we had so vehemently disregarded when we ushered in the Age of Science. This is where Quantum Mechanics leads us ultimately, back to these very same questions about meaning but not necessarily about the meaning of life or the cosmos but the meaning of meaning itself. How do we bound knowledge and how do we know what we know? Back to first philosophy again. Back to metaphysics. Kant is rolling over in his grave to be sure.

Our answer to this question, the question of how to approach our knowledge of the world and what can be trusted, what can truly be known, what can be said to be true, has been since at least the post-Enlightenment era, Science. It is via science, as it is managed and heralded by the Academy primarily, via the scientific method of inquiry and experimental verification, by which we have all (mostly) agreed is a very good benchmark for truth. It has no doubt served us well. Quantum Mechanics fits into this category, as does Physics more generally. Certainly the engineering disciplines such as Computer Science, I mean what’s more empirical than a machine after all? All of these fields distinguish themselves from the rest of the sciences, and the humanities more broadly, in resting their truths primarily on empirical data, experimental results, and very specific algebraic and mathematical formulations which seem to be true (relatively speaking and stochastically speaking to be sure) in all possible times and places in this universe. At least as far as we can gather at this point, singularities (black holes) aside.

This is no doubt a very good baseline to start with, a good sort of shared denominator of understanding that we can all use to at least come to some basic conclusions about the nature of the world, how it was created and how it works. But where it falls short is really in any of the non-material domains of understanding, the realms of so-called subjective experience, which certainly include psychology, and theology (religion), and philosophy generally outside of natural philosophy (as Aristotle called it), which for better or worse are what you might call necessary conditions (of understanding) for any sort of explanation as to what the meaning of all of this (life, existence, etc.) is and, more specifically as it relates to the exercise at hand, how it is that meaning itself is related to our experience of the world.

This represents for better or worse a massive body of knowledge that not only connects us with everyone else on the planet (as shared experience), but also every other human that has existed on this planet before us, and as it turns out, as the ancients held in fact, is the very essence of (subjective) experience itself – namely meaning. To experience a rock for example, to hold it in your hand, without knowing what it is, how it came to be, or what it can be used for is, or its relationship to the earth and the rivers and the trees from which it came, is an empty experience to be sure. Empty from the vantage point of meaning, of understanding. We would know what it feels like, how heavy it feels, what it looks like, what color it is, but beyond these basic physical properties we would not know very much at all about such a thing that we held in our hand. It’s from this search for meaning, this endeavor to define the boundaries of meaning itself, from which Aristotle’s four causal theory of knowledge comes from (material, formal, efficient and final).

So where that leaves us, from a ‘scientific’ standpoint at least, from what we have called elsewhere the objective realist (philosophical) position, a position that in no small measure could be argued as characteristic of the modern, Western worldview (and I am most certainly not the first one to recognize or even grapple with this issue), is that while we have a very good understanding of how to manipulate and navigate through and about the world of matter, we are nonetheless left with very real and very meaningful (no pun intended) gaps in our understanding, our knowledge broadly speaking, of what we should be doing with ourselves to take advantage of all of these technologies that are at our fingertips that make our lives so much easier than all of the thousands of generations of humanity that have come before us.

The problem with this of course is that if these questions are left unanswered, if they continue to be cast aside as philosophical musings with no real practical value, we continue along this path of not just empty lives, lives with no real meaning and purpose, but with lives that are not only disconnected from each other but disconnected from the planet and the cosmos itself, which in turn yield to outcomes that that have very real, very physical, consequences for not just humanity but for the Earth as a whole. We need to get a handle on these questions in order for humanity to move into the next phase of its existence, in order for it to continue to thrive without destroying its host so to speak. This is the challenge of our Era, the problem that faces our generation and the generations to follow us, this is our great calling.

Solves for these types of problems, the answers to these fundamental questions, must engage with philosophy, and this is how the discipline was conceived of in antiquity at least, what Aristotle called first philosophy, which was intended to provide at least some of the answers to these basic questions about how the world came into being and what our place in the world is, and thereby providing some guidance as to how to navigate in the world. It’s from these initial efforts in fact that the word metaphysics itself emerged as the branch of knowledge within philosophy that addressed such questions, a topic to be delved into after, ‘meta’, Physics, or natural philosophy in Aristotelian parlance.

This is how metaphysics was originally scoped and defined in antiquity, at least in the Western philosophical tradition, and this demarcation between natural philosophy and first philosophy held sway in the West through the Middle Ages until the Enlightenment, after which, from an intellectual perspective at least, Science, and the scientists who practiced said arts, were finally allowed to do their work unencumbered by the dogmatic ideology of the Church. This subtle and yet profound change in the unshackling of Science from Religion has in turn of course led to the most radical advance of knowledge in the history of our species, giving us the technological infrastructure to feed almost the entire planet, the ability to see into the far reaches of space, and perhaps most significantly with respect to the work herein, the ability to store, process and transmit seemingly limitless amounts of information from anywhere in the world, to anywhere in the world, in almost near real-time.

Science (literally from the Latin scientia, or scire, the verb to ‘to know’) tells us how things work, how we can build things for a (presumably) better world, but again t doesn’t address any of life’s basic questions – namely what the true nature of this world is and what we are (supposed to be) doing here. This is, as I have discussed in great detail, a terrible bastardization of the notion of knowledge as it was understood by the very founders of the Western intellectual tradition – Plato and Aristotle in particular who both held much more expansive views of what it is to know and what it is that can be known – a discipline in (modern) philosophy that is known as epistemology, a word whose root comes from the ancient Greek word for knowledge, i.e. epistēmē.

Much of this problem I cover Theology Reconsidered (Valdez 2019) and there is no need to rehash these intellectual building blocks here, how they should be constructed and how they have evolved over time to underpin our more modern notions of what it is that can be known, but suffice it to say that while epistemology is very healthy and active field of study in philosophical circles, it’s relevance and applicability for understanding the nature of this world and how to live, which is how the discipline was originally formulated, is tangential at best and at worst completely of no consequence.

Knowledge at some level, given the scientific nature of post-Enlightenment civilization, is equated with science to a large degree, and as such is rooted in a physicalist and materialist conception of reality and as such has limited applicability. The main problem with this, and again emphasizing how important it was and is that science be able to flourish independently of any influence by political or religious institutions (enter academia), is that it includes just half of life experience. Maybe even less than half.

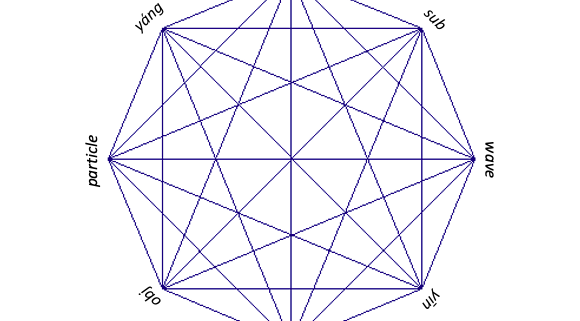

The half that science is concerned with of course is objective reality, the world according to Physics, the world which according to Kant – a philosophical position that we take as fundamental throughout – relates to the world of things, objects per se, as they can be understood to exist independent of human experience, the so-called noumenal world. The problem with this, and what Quantum Mechanics brings to the fore in fact, is that our understanding of the world, our understanding of objective reality, is fundamentally governed by not just observables necessarily, but also by our mind/body complex which is specifically designed to both perceive and conceive of said observables and in turn make sense of them. To know that a rock weighs 6 lbs. we need to know what weight means and certainly what lbs. means. This seemingly trivial point is brought to the very forefront of Physics itself with Quantum Mechanics, where the very design of the measurement apparatus, i.e. the experiment, itself determines whether or not the thing it is that we are measuring (an electron or a photon for example) behaves like a wave or a particle.

This is the current state of modern Physics, that in fact these subatomic ‘things’ are really not waves or particles like we normally understand these things to be within the context of Classical (Newtonian) Physics, but they are something else entirely – flashing, swirling vortexes of energy that adapt to their surroundings (experimental apparatus) and inherently ‘know’ about their environment in a way that crosses the boundaries of spacetime as it is understood with Relativity. These are the basic descriptions of the properties of non-locality and wave-particle duality that make the study of Quantum Mechanics, at least from an interpretative standpoint, so darned frustrating at times.

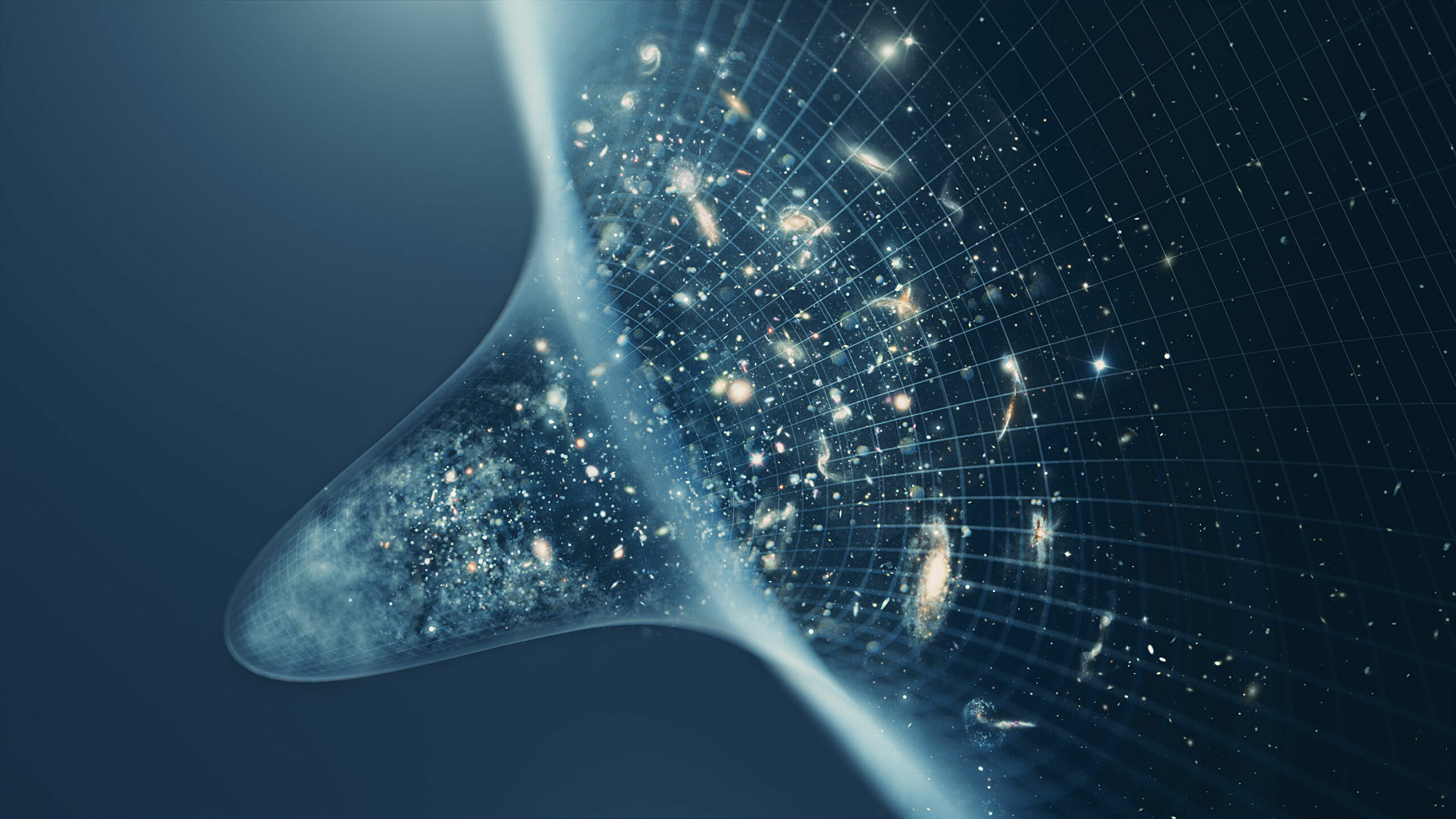

With the ‘discovery’ of the laws of Quantum Mechanics in the first half of the twentieth century, and it’s fundamentally non-classical tenets, a wide variety of interpretations have cropped up, suggesting that our universe is really a multi-verse, and each of the possible paths of the quantum wave actually corresponds to some form of reality (Dewitt/Graham 1973), spurring even more abstract mathematical models like string theory that proposes that our world is really nothing but the vibration of these tiny, multi-dimensional strings from which both matter, time and space emerge. (Susskind 2006)

But one of the fundamental questions that has been raised since the theory’s inception, by one of its founders no less, the Hungarian American mathematician John von Neumann, is the role that the observer himself plays in the result of the Quantum experiment, in the process of ‘measurement’ as it is typically referred to as. This integral role of the observer has been more generally applied to the role of mind, or consciousness, through which many physicists, and other philosophers of science, have hypothesized as the source of the very odd and strange mathematical construct called wavefunction collapse which is what happens, mechanically and mathematically speaking, once an act of measurement is made by an observer (of a quantum system).

In this interpretation of quantum theory, the variant that is attributed to Von Neumann, Wigner, Stapp and others, it is consciousness (or mind as we envision it herein) that is the cause of the so-called measurement problem, which in turn causes the so-called wavefunction collapse that so defines explanation from a classical mechanical point of view as put forward by the theoretical frameworks advanced by both Newton and Einstein (see Atmanspacher 2020; Stapp 2001, 2009; Thaheld 2005; Valdez 2017).

This interpretation of course sits in stark contrast in fact to the classical, orthodox interpretation put forward by Heisenberg and Bohr, two of the founding fathers of Quantum Mechanics (the so-called Copenhagen Interpretation), which asserts that no metaphysical conclusions should be drawn at all from the mathematical formulation of Quantum Mechanics, it’s just a calculating discipline to predict the outcomes, at least stochastically (probabilistically) of experiments conducted at the Planck scale.

Much has been written about this, and we will not attempt to summarize the findings here necessarily, but what we will point out though is that in order to reconcile some of the basic paradoxical conclusions of quantum mechanics and classical mechanics (e.g. around wave-particle duality, uncertainty and non-locality) one must look for higher order intellectual paradigms, just as Einstein advises us in fact with the sage advice which I paraphrase here, no problem can be solved using the same intellectual paradigm through which the problem was created in the first place.

The general approach within the physicist, and mathematical community has been – not surprisingly – to search for more advanced and abstract mathematical constructs that can explain how it is that both Classical Mechanics (Relativity in its post Einsteinian form) and Quantum Mechanics can both in fact be true, as we believe them both to be given their predictive and explanatory power that has been proven time and time again empirically. But we are still left with the question about what it is that this math is actually telling us, what does it actually mean?

Invariably this gets into the interpretive domain which in turn leads us into philosophical waters (philosophy of science, epistemology, metaphysics, ontology, etc.). And while some very interesting developments have been made in this area, on the philosophical side of the house so to speak, much of the underlying connection to mathematical, geometric and algebraic rigor has been lost. This is not true in all cases, but certainly from a philosophical perspective it’s fair to say that mathematical rigor is somewhat lacking. It is in this intellectual gap so to speak, that we offer up this work as a (potential) solution to some of the problems that arise from the paradoxes that emerge from Quantum Mechanics as they relate to Classical Mechanics, again as put forward by Newton and Einstein and others.

To this end, we lean on the work of many academics and scientists that have explored various ways to integrate consciousness, again the mind, into physics like the aforementioned Von Neumann, Wigner, and Stapp but also others such as Pradhan (Pradhan 2012), Manousakis (Manousakis 2006) and Blaha (Blaha 2009), all of which who have looked at various ways to interpret the underlying mathematics itself to reveal how it is that consciousness, or again the conscious mind, can be understood as ‘operating’ within the paradigm itself to cause this phenomena of wavefunction collapse. Our work here is intended to build on said work and expend it, in particular within the context of both the Western and Eastern philosophical tradition, such that a more complete understanding of its meaning, epistemologically, can at least be approached.

Fundamentally then, Quantum Mechanics presents us with the question of epistemology, i.e. how it is we are to conceive of knowledge generally speaking and how it is that we can understand our (subjective) experience of the (objective) world, the world of Nature and the world of Physics as it is typically understood. Ultimately the question seems to boil down to the question of whether or not we participate in the creation of our reality, and if so how and to what extent? Given that we know that matter is really another form of energy, what is it that really matters anyway?

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!